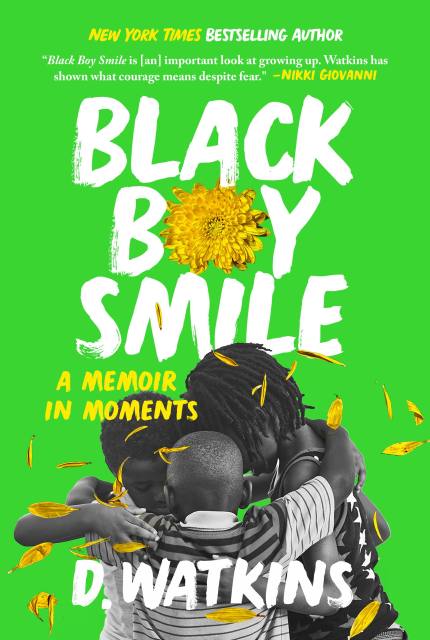

Black Boy Smile

A Memoir in Moments

Contributors

By D. Watkins

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $27.00 $34.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 16, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

"If I had two wishes, it would be that D. Watkins spend an entire book writing through the terrifying wonder of Black boyness in America, and for every human to read and share this book. I am shaken. Black Boy Smile changed my relationship to writing and me."―Kiese Laymon, author of Heavy and winner of the Andrew Carnegie Medal

At nine years old, D. Watkins has three concerns in life: picking his dad’s Lotto numbers, keeping his Nikes free of creases, and being a man. Directly in his periphery is east Baltimore, a poverty-stricken city battling the height of the crack epidemic just hours from the nation’s capital. Watkins, like many boys around him, is thrust out of childhood and into a world where manhood means surviving by slinging crack on street corners and finding oneself on the right side of pistols. For thirty years, Watkins is forced to safeguard every moment of joy he experiences or risk losing himself entirely. Now, for the first time, Watkins harnesses these moments to tell the story of how he matured into the D. Watkins we know today—beloved author, college professor, editor-at-large of Salon.com, and devoted husband and father.

Black Boy Smile lays bare Watkins’s relationship with his father and his brotherhood with the boys around him. He shares candid recollections of early assaults on his body and mind and reveals how he coped using stoic silence disguised as manhood. His harrowing pursuit of redemption, written in his signature street style, pinpoints how generational hardship, left raw and unnurtured, breeds toxic masculinity. Watkins discovers a love for books, is admitted to two graduate programs, meets with his future wife, an attorney—and finds true freedom in fatherhood.

Equally moving and liberating, Black Boy Smile is D. Watkins’s love letter to Black boys in concrete cities, a daring testimony that brings to life the contradictions, fears, and hopes of boys hurdling headfirst into adulthood. Black Boy Smile is a story proving that when we acknowledge the fallacies of our past, we can uncover the path toward self-discovery. Black Boy Smile is the story of a Black boy who healed.

-

“Black Boy Smile is a must-read exploration of white supremacy, toxic masculinity, and the need to undermine them both.”Booklist, Starred Review

-

"A startling and moving celebration of a brutal life transformed by language and love."Kirkus Books, Starred Review

-

“Reading this memoir is like going through a pile of pictures with author D. Watkins…Black Boy Smile has the sweet kind of ending you want in a memoir, and that’s the honest truth.”Washington Informer

-

“Black Boy Smile will make you smile, too. [It] has the sweet kind of ending you want in a memoir, and that’s the honest truth.”Philadelphia Tribune

-

“A smile isn't a thing that appears on the face in a flash. It's more of a gradual lift that starts from an unseen place. What Watkins does here is courageously chronicle that lift. This is, no doubt, an origin story for the ages.”Jason Reynolds, New York Times bestselling author and National Book Award finalist

-

"If I had two wishes, it would be that D. Watkins spend an entire book writing through the terrifying wonder of Black boyness in America, and for every human to read and share this book. I am shaken. Black Boy Smile changed my relationship to writing and me."Kiese Laymon, author of Heavy and winner of the Andrew Carnegie Medal

-

“Black Boy Smile is another important look at growing up. Watkins has shown what courage means despite fear. This is a book all young men should read.”Nikki Giovanni, American poet and NAACP Image Award winner

-

“In Black Boy Smile, D. Watkins is a masterful memoirist. No lie, I could read accounts from his life for eons. He writes with so much style and verve; so much wit, humor, candor; so much cultural acuity and earned wisdom. Watkins miraculous personal story is a universal testimony of survival, love, and hard-won evolution. This book should be required reading for every Black man in America, plus everybody who knows one.”Mitchell S. Jackson, Pulitzer Prize and Whiting Award winner and author of Survival Math.

-

"In Black Boy Smile, D. Watkins excavates his past and lays bare his present and future, writing with the kind of deep honesty and vulnerability that take you from the pages of a memoir directly into the writer’s tender heart. . .A powerful, timely meditation on Black masculinity, survival, loss, grief, and love."Deesha Philyaw, National Book Award finalist and author of The Secret Lives of Church Ladies

-

"A staggering account of Black boyhood in its abounding scope, a gift for so many of us who've grown used to consuming misrepresentations about the men we love most. This is a book that has left nothing out. Each essay is more radically honest than the last, yet painfully obvious, so Black Boy Smile exposes not only the historical and spiritual institutions at the root of those diminished smiles, but the ways in which each of us are complicit in upholding those structures. A compulsive, affecting, beautiful read."Wayétu Moore, author of She Would Be King and The Dragons, the Giant, the Women

-

“D. Watkins has long been one of our most profound memoirists... The scenes are so full of life, the prose so masterful that I was lost in D.'s world. I dare you to read the first chapter and then try to put this book down.”Baynard Woods, author of Inheritance

-

On We Speak for Ourselves: "[D. Watkins] is not another elite voice for the voiceless. He is, this book is, an amplifier of low income Black voices who have their own voices and have no problem using them. He dares us to listen.”Ibram X. Kendi, author of How to Be an Anti-Racist

-

On We Speak for Ourselves: “Watkins’ latest work shows the black community is not a monolith. Even as we may wear the iconic t-shirts of the struggle yet have different thoughts about the issues faced. We are a diverse and proud community, trying to come to grips with who we are; sometimes wearing a mask within our own brother and sisterhood."April Ryan, author of Under Fire

-

On We Speak for Ourselves: "Watkins writes with a type of profound love for the Black forgotten that will compel all who read his timely words to never forget the Black people and places so many cultural critics and thought leaders disremember with ease.”Darnell L. Moore, author of No Ashes in the Fire

-

On The Cook Up: “Amazing storytelling that brings us deep into the reality of East Baltimore. A moving and important piece of contemporary memoir.”Wes Moore, author of The Work and The Other Wes Moore

-

On The Cook Up: "An unflinching, raw, coming-of-age account of the personal impact of the drug trade. Simply a must-read.”DeRay Mckesson, author of On the Other Side of Freedom

-

On D. Watkins: "That Watkins threaded his way from those corners to the page is rare enough. That he is so committed to pulling this world through with him—enough of it to at least rub our noses in it and make us acknowledge some collective responsibility—is precious."David Simon, author of The Corner and Creator of HBO's The Wire

-

On D. Watkins: “Watkins’ latest work shows the black community is not a monolith. Even as we may wear the iconic t-shirts of the struggle yet have different thoughts about the issues faced. We are a diverse and proud community, trying to come to grips with who we are; sometimes wearing a mask within our own brother and sisterhood."Jada Pinkett Smith, American actress

-

On The Cook Up: "An important story for both Black and white America, as well as this country’s political leadership, to read, if we’re truly going to tackle the challenges that are facing our communities all across the country.”Chuck Todd, correspondent, NBC's Meet the Press

- On Sale

- May 16, 2023

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Legacy Lit

- ISBN-13

- 9780306923982

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use