By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

The Tower of Fools

Contributors

Translated by David French

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 27, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

"A fantastic novel that any fan of The Witcher will instantly appreciate." —The Gamer

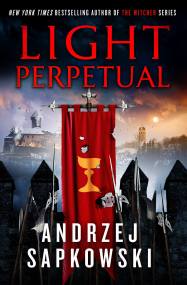

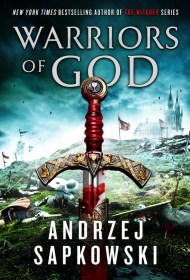

Andrzej Sapkowski's Witcher series has become a fantasy phenomenon, finding millions of fans worldwide and inspiring the hit Netflix show and video games. Now the bestselling author introduces readers to a new hero on an epic journey in The Tower of Fools, the first book of the Hussite Trilogy.

Andrzej Sapkowski's Witcher series has become a fantasy phenomenon, finding millions of fans worldwide and inspiring the hit Netflix show and video games. Now the bestselling author introduces readers to a new hero on an epic journey in The Tower of Fools, the first book of the Hussite Trilogy.

Reinmar of Bielawa, sometimes known as Reynevan, is a healer, a magician, and according to some, a charlatan. When a thoughtless indiscretion forces him to flee his home, he finds himself pursued

not only by brothers bent on vengeance but by the Holy Inquisition.

In a time when tensions between Hussite and Catholic countries are threatening to turn into war and mystical forces are gathering in the shadows, Reynevan's journey will lead him to the Narrenturm—the Tower of Fools.

The Tower is an asylum for the mad…or for those who dare to think differently and challenge the prevailing order. And escaping it, avoiding the conflict around him, and keeping his own sanity will prove more difficult than he ever imagined

"A ripping yarn delivered with world-weary wit, bursting at the seams with sex, death, magic and madness." —Joe Abercrombie

"A ripping yarn delivered with world-weary wit, bursting at the seams with sex, death, magic and madness." —Joe Abercrombie

"This is historical fantasy done right." —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

"A highly enjoyable historical fantasy." —Booklist

"A highly enjoyable historical fantasy." —Booklist

The Tower of Fools is an historical novel set during the Hussite Wars in Bohemia during the 1400s, a period of religious conflict and persecution. Characters in the novel may express views that some readers might find offensive.

Also by Andrzej Sapkowski:

Witcher collections

The Last Wish

Sword of Destiny

Witcher novels

Blood of Elves

The Time of Contempt

Baptism of Fire

The Tower of Swallows

Lady of the Lake

Season of Storms

The Malady and Other Stories: An Andrzej Sapkowski Sampler (e-only)

Translated by David French

Genre:

Series:

-

"Sapkowski's love for the period is clear as he touches on notorious historical events and figures ... The carefully painted landscapes and intricate politics effortlessly draw readers into Reinmar's life and times. This is historical fantasy done right."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"A ripping yarn delivered with world-weary wit, bursting at the seams with sex, death, magic and madness."Joe Abercrombie

-

"Sapkowski's energetic and satirical prose as well as the unconventional setting makes this a highly enjoyable historical fantasy. Recommended for Sapkowksi's many existing fans."Booklist

-

"[The Tower of Fools] is a fantastic novel that any fan of The Witcher will instantly appreciate . . . Reynevan is an intelligent dope who follows his heart, his accompanying cast of characters is thoroughly developed and just as intriguing, and the worldbuilding employed by Sapkowski is impeccable."The Gamer

-

“Sapkowski’s primary draw is his ability to weave rich historical context with a complex atmosphere of magic and superstition . . . [The Tower of Fools] is quite rewarding for readers ready to take the plunge.”BookPage

-

"A story full of intrigue, politics, and murder is brought to life by Kenny in a smooth narrative style. Thanks to his vivid depiction of this fantasy world and its characters, listeners will eagerly await the second installment."AudioFile

-

"The action is wonderfully done. Also a delight is the subtle humor….The author has also gifted us with the very popular Witcher series, books and film, but I enjoyed the link to real history even more."Historical Novel Society

- On Sale

- Oct 27, 2020

- Page Count

- 560 pages

- Publisher

- Orbit

- ISBN-13

- 9780316705356

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use