Promotion

Use code SPOOKY24 for 20% off sitewide! Exclusions apply.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

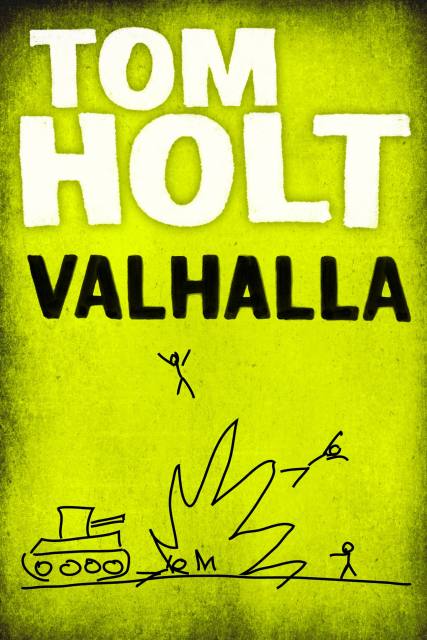

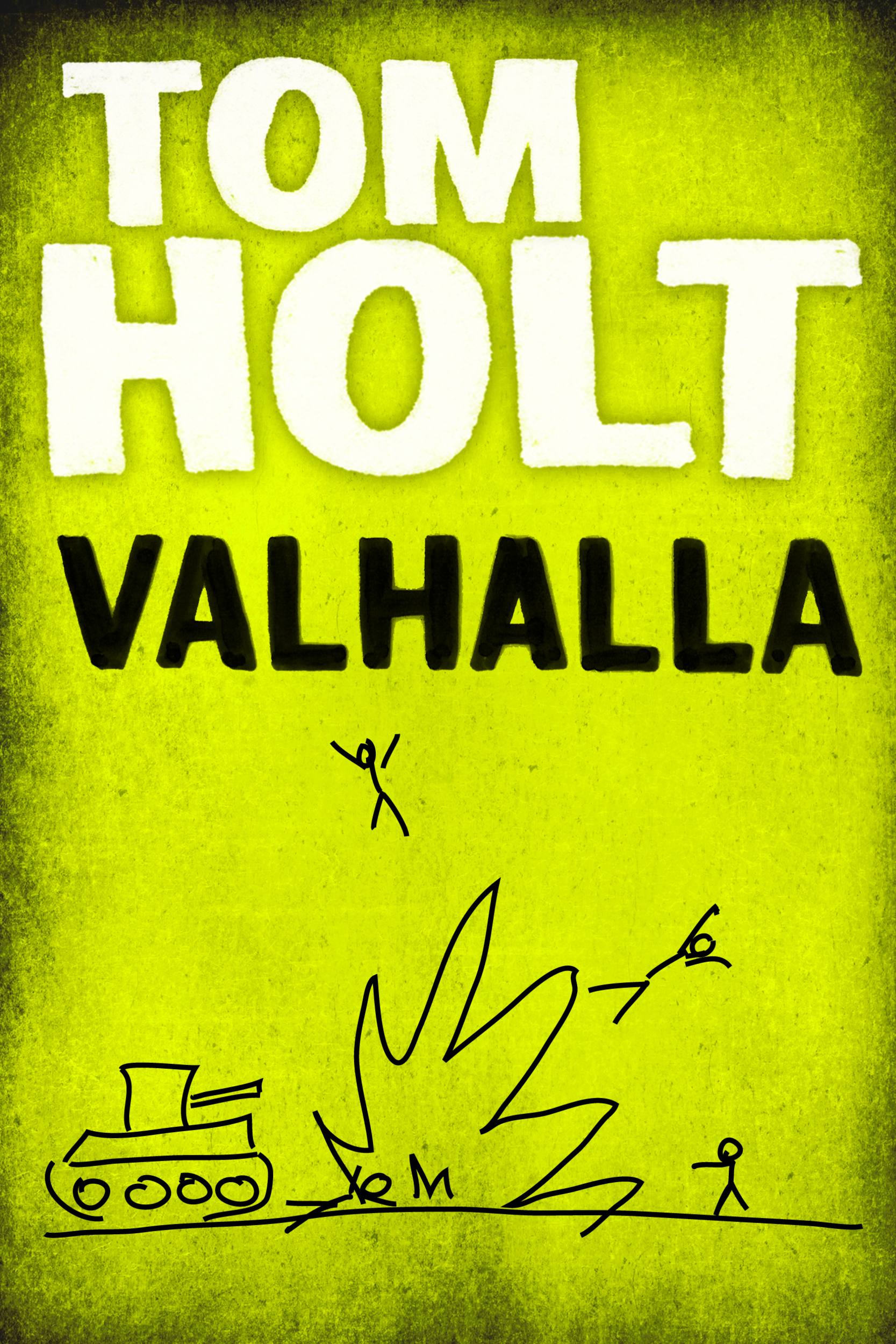

Valhalla

Contributors

By Tom Holt

Formats and Prices

Price

$3.99Format

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $3.99This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 4, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

As everyone knows, when great warriors die, their reward is eternal life in Odin’s bijou little residence known as Valhalla. But Valhalla has just changed. It has grown. It has diversified. Just like any corporation, the Valhalla Group has had to adapt to survive. Unfortunately, not even an omniscient Norse god could have prepared Valhalla for the arrival of Carol Kortright, one-time cocktail waitress, last seen dead, and not at all happy.

- On Sale

- Sep 4, 2012

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Orbit

- ISBN-13

- 9780316233439

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use