Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

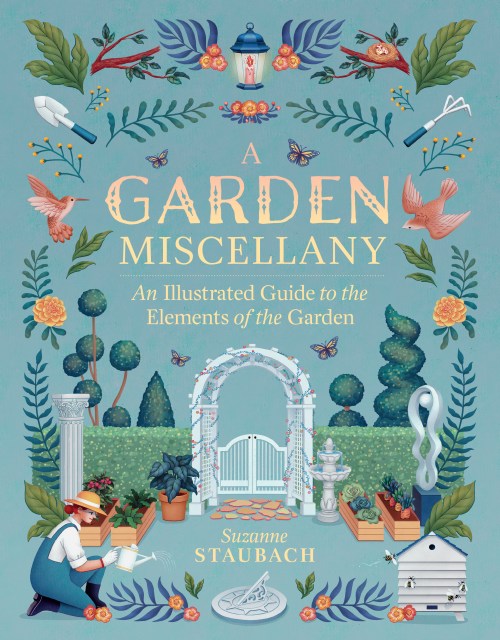

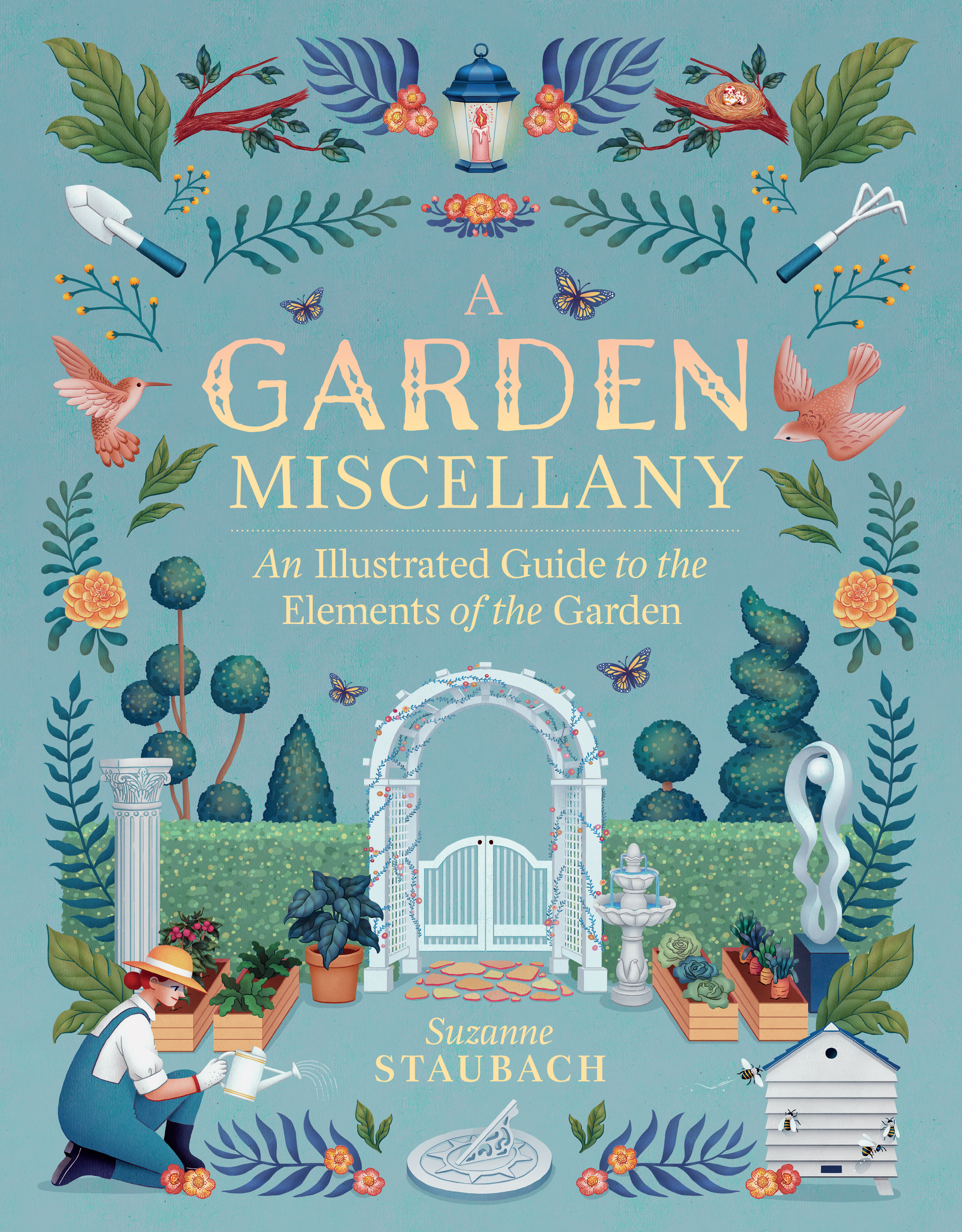

A Garden Miscellany

An Illustrated Guide to the Elements of the Garden

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.50Price

$32.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.50 $32.95 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 29, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

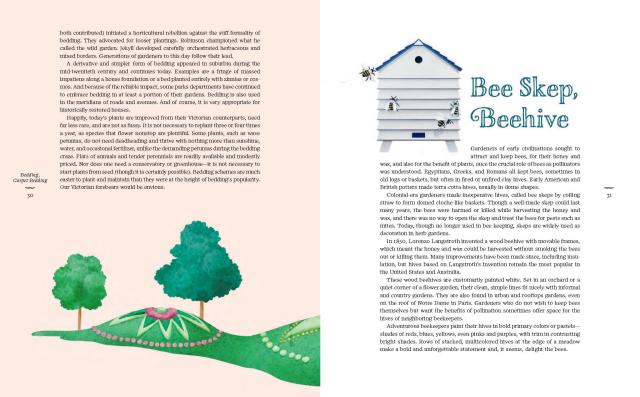

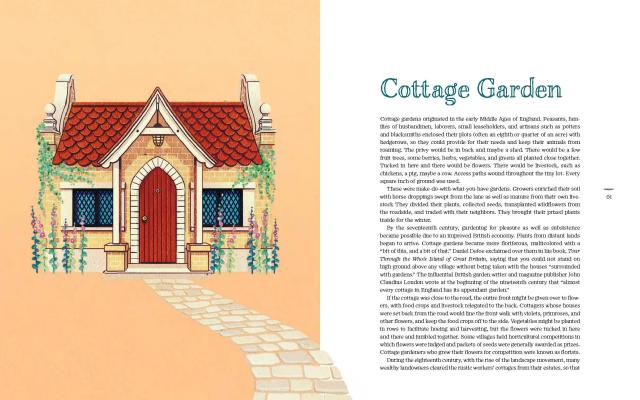

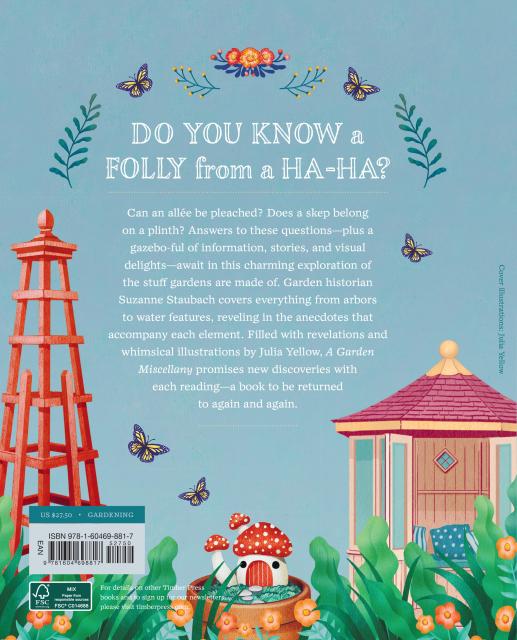

Do you know a folly from a ha-ha? Can an allée be pleached? Does a skep belong on a plinth? Answers to these questions—plus a gazebo-ful of information, stories, and visual delights—await in this charming exploration of the stuff gardens are made of. Garden historian Suzanne Staubach covers everything from arbors to water features, reveling in the anecdotes that accompany each element. Filled with revelations and fanciful illustrations by Julia Yellow, A Garden Miscellany promises new discoveries with each reading—a book to be returned to again and again.

Genre:

-

“The right amount of useful advice and, when applicable, educational historical tidbits… Julia Yellow’s whimsical illustrations, generously scattered throughout, ensure the work remains charming as well as informative. This is both a pleasure to read and a valuable resource to fall back on for the enthusiastic gardener.” —Publishers Weekly

“A sweet, alphabetical handbook to all things green, from arbors and arches to water features and yards. The painterly illustrations, quirky factoids and genuinely helpful tips make this an ideal gift for anyone who has a garden…or just imagines escaping to one.” —The New York Post

“Lovely illustrations make this informative book a pleasure to return to again and again.” —The Seattle Times

“Any gardener will enjoy the clever, useful prose and storytelling illustrations…The pretty cover, with gold foil detailing, already seems wrapped for giving.” —The Oregonian

“A perfect gift for the gardener in your life, with little anecdotes about odd garden features, and charming illustrations.” —The Multnomah County Library

“Quirky illustrations and headings either bring levity to what might appear to be a dry topic, or diminish its intellectual heft, depending on your point of view… the perspective is enlightening and helps to paint a fuller picture of the items we use almost daily.” —The English Garden

“A unique book that blends the practical with the poetic.” —Horticulture

“Filled with revelations and fanciful illustrations, this whimsical book is part garden guide and part coffee table art. Whether used as a reference guide or a quick pleasure read, it promises new discoveries with each opening.” —Michigan Gardener

- On Sale

- Oct 29, 2019

- Page Count

- 220 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781604698817

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use