Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

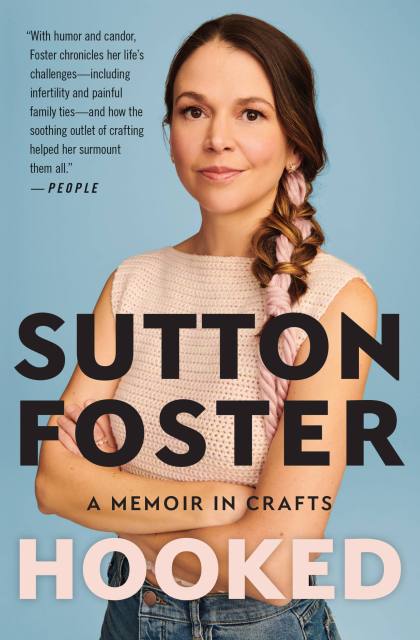

Hooked

How Crafting Saved My Life

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 12, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Whether she’s playing an “age-defying” book editor on television or dazzling audiences on the Broadway stage, Sutton Foster manages to make it all look easy. How? Crafting. From the moment she picked up a cross stitch needle to escape the bullying chorus girls in her early performing days, she was hooked. Cross stitching led to crocheting, crocheting led to collages, which led to drawing, and so much more. Channeling her emotions into her creations centered Sutton as she navigated the significant moments in her life and gave her tangible reminders of her experiences. Now, in this charming and poignant collection, Sutton shares those moments, including her fraught relationship with her agoraphobic mother; a painful divorce splashed on the pages of the tabloids; her struggles with fertility; the thrills she found on the stage during hit plays like Thoroughly Modern Millie, Anything Goes, and Violet; her breakout TV role in Younger; and the joy of adopting her daughter, Emily. Accompanying the stories, Sutton has included crochet patterns, recipes, and so much more!

Witty and poignant, Hooked will leave readers entertained as well as inspire them to pick up their own cross stitch needles and paintbrushes.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 12, 2021

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538734278

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use