By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

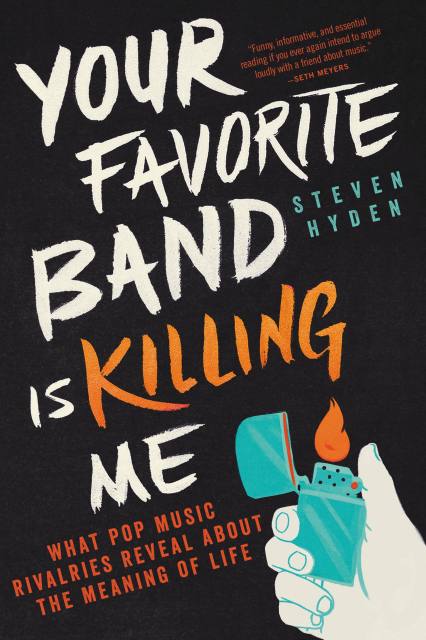

Your Favorite Band Is Killing Me

What Pop Music Rivalries Reveal About the Meaning of Life

Contributors

By Steven Hyden

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 17, 2016

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316259149

Price

$8.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $8.99 $11.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 17, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Beatles vs. Stones. Biggie vs. Tupac. Kanye vs. Taylor. Who do you choose? And what does that say about you? Actually — what do these endlessly argued-about pop music rivalries say about us?

Music opinions bring out passionate debate in people, and Steven Hyden knows that firsthand. Each chapter in Your Favorite Band Is Killing Me focuses on a pop music rivalry, from the classic to the very recent, and draws connections to the larger forces surrounding the pairing.

Through Hendrix vs. Clapton, Hyden explores burning out and fading away, while his take on Miley vs. Sinead gives readers a glimpse into the perennial battle between old and young. Funny and accessible, Hyden's writing combines cultural criticism, personal anecdotes, and music history — and just may prompt you to give your least favorite band another chance.

Genre:

-

"Highly entertaining.... Whatever side you take in these endless debates, Hyden's a dude worth arguing with."Rolling Stone

-

"Consistently insightful and funny...Your Favorite Band Is Killing Me connects the dots of music history in new and intriguing ways. Hyden reminds us why we invest so much in these competitions, how they help shape identity for so many of us, while never losing sight of how silly they can be."Alan Light, New York Times Book Review

-

"Fluent, frequently hilarious, ultimately persuasive.... [Hyden's] as entertaining on Eric Clapton vs. Jimi Hendrix (chapter 7) as he is on Taylor Swift vs. Kanye West (chapter 5).... Hyden [is] a critic worth reading."Chris Klimek, Washington Post

-

"Funny, informative and essential reading if you ever again intend to argue loudly with a friend about music."Seth Meyers

-

"Steven Hyden didn't come to settle your rock arguments--just to make them louder. In this brilliant book, he pours a little kerosene on some of music's most heated feuds--some legendary, some forgotten, one involving Limp Bizkit. Your Favorite Band Is Killing Me is not only hilarious but surprisingly moving--Hyden captures the secret emotional details of why these stories matter, and how picking sides can accidentally tell you way too much about who you are."Rob Sheffield, author of Love is a Mix Tape

-

"Every serious argument about music is ultimately a non-musical manifesto--it's 10 percent about aesthetics, 40 percent about how the respective arguers view the world, and 50 percent about how those arguers view themselves. Steven Hyden lives inside this ratio and argues with himself, which means it's impossible to win. But that's what makes YOUR FAVORITE BAND IS KILLING ME so fascinating: The title is real. He's funny, but he's not joking."Chuck Klosterman, author of Fargo Rock City and Killing Yourself to Live

-

"If Nick Hornby's writing had a love child with Chuck Klosterman's, the result would be Hyden's clever prose.... By combining music journalism and pop psychology with some of his own life lessons, Hyden has created a literary mix tape that will be music to pop-culture junkies and the music-obsessed."Publishers Weekly

-

"Even the most knowledgeable music fan will learn from Hyden's musings, and anyone with a sense of humor will find his prose laugh-out-loud funny.... An outstanding piece of pop culture writing for readers who consider music an important part of their lives."Craig L. Shufelt, Library Journal (starred review)

-

"Hyden is an effortless writer, and he draws clever connections between artists and cultural phenomena spanning decades.... Illuminating and often hilarious.... Hyden is wise enough to know that declaring a winner is pointless (and so the book never does), but smart enough to discuss everything that might come with 'winning.'"Jeremy Gordon, Pitchfork

-

"Rich with unexpected tangents and entertaining insights, the book reveals Hyden's well-established talent for pumping out some of the most thoughtful writing on some of the least-cool artists (at least in critical corners)."Zach Schonfeld, Newsweek

-

"Steven Hyden is one of the most original, thoughtful pop culture writers out there."Bill Simmons, author of The Book of Basketball

-

"I learned a lot, I laughed a lot, I dug out my old Oasis CDs. Your Favorite Band Is Killing Me is so authoritative, informative, compelling, and stone-cold hilarious that I am hereby initiating a beef with Steven Hyden."Dave Holmes, author of Party of One

-

"Funny, smart and will provide fodder for the next time you get together with your music-loving friends."Deborah Dundas, Toronto Star

-

"A funny book that is also full of ideas -- especially about how people relate to culture and how meaning changes as we age."Scott Timberg, Salon

-

"Wildly readable... No matter who you might be on any rock-aware cultural spectrum, this is great fun. But it's a bit more than just that, too."Jeff Simon, The Buffalo News

-

"With sharp, nail-on-the-head observations, Steven Hyden dives into the minutiae of what we all know is the most important conflict of modern times but are too embarrassed to admit: Who is the cooler band? Who is the better band? Why are they better/cooler? Are they better because they are cooler, or vice versa? Have I blown your mind yet? Then just imagine what this book will do."Adam Scott, star of Parks and Recreation and Party Down and co-host of U Talkin' U2 to Me?

-

"Steven Hyden works a tangent like a barroom storyteller.... Funny and insightful."Ken Szymanski, Volume One

-

"Hyden masterfully weaves together disparate narratives to reveal the themes we embrace when we pick sides in pop music."Josh O'Kane, The Globe and Mail

-

"For my money, the best current music writer out there is Steven Hyden. His profile and feature writing joins the keen observation of a journalist with the true-believer mentality of a rock fan."Aarik Danielsen, Columbia Daily Tribune

-

"Well-researched, hilariously written and solidly conceptualized, Your Favorite Band is Killing Me is a winding crash course through the last 50 years of feuding pop stars and the people who back them, with a narrator who can seamlessly reconcile and separate his own journey with that of the public view. Hyden's well-honed vision has forged a book that covers a broad berth of events and ideas with hyper-specific examples to uncover the relatable human truths in the middle."Matt Bobkin, National Post

-

"Your Favorite Band Is Killing Me is entertaining, hilarious, and thought provoking. It uses feuds in music and pop culture to explain something about all of us, our behavior, and our strange need for these spats between show business people. I had a great time reliving some musical arguments of my youth, but it also made me realize just how weird the 90s were--really, really weird."Craig Finn of The Hold Steady

-

"A pop-culture journey to self-realization that makes some intriguing stops."Kirkus Reviews

-

"One of the various ways the book seems to be connecting with readers ... is Hyden's ability to take these debates and use them to find understanding, not just about the culture but also his own life."Shane Nyman, Appleton Post Crescent

-

"An entertaining, informative look at rivalries in pop music."Michael Schaub, Men's Journal

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use