Music

A Subversive History

Contributors

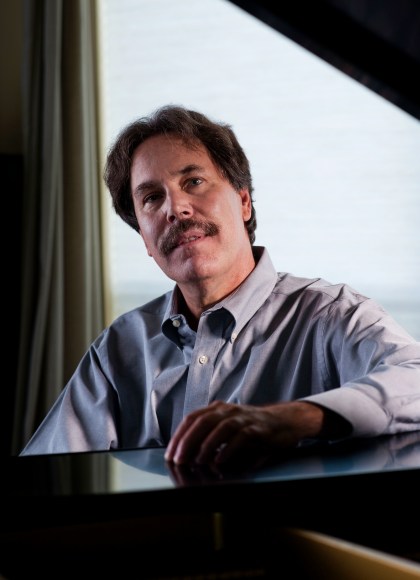

By Ted Gioia

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 20, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

"A dauntingly ambitious, obsessively researched" (Los Angeles Times) global history of music that reveals how songs have shifted societies and sparked revolutions.

Histories of music overwhelmingly suppress stories of the outsiders and rebels who created musical revolutions and instead celebrate the mainstream assimilators who borrowed innovations, diluted their impact, and disguised their sources. In Music: A Subversive History, Ted Gioia reclaims the story of music for the riffraff, insurgents, and provocateurs.

Gioia tells a four-thousand-year history of music as a global source of power, change, and upheaval. He shows how outcasts, immigrants, slaves, and others at the margins of society have repeatedly served as trailblazers of musical expression, reinventing our most cherished songs from ancient times all the way to the jazz, reggae, and hip-hop sounds of the current day.

Music: A Subversive History is essential reading for anyone interested in the meaning of music, from Sappho to the Sex Pistols to Spotify.

Histories of music overwhelmingly suppress stories of the outsiders and rebels who created musical revolutions and instead celebrate the mainstream assimilators who borrowed innovations, diluted their impact, and disguised their sources. In Music: A Subversive History, Ted Gioia reclaims the story of music for the riffraff, insurgents, and provocateurs.

Gioia tells a four-thousand-year history of music as a global source of power, change, and upheaval. He shows how outcasts, immigrants, slaves, and others at the margins of society have repeatedly served as trailblazers of musical expression, reinventing our most cherished songs from ancient times all the way to the jazz, reggae, and hip-hop sounds of the current day.

Music: A Subversive History is essential reading for anyone interested in the meaning of music, from Sappho to the Sex Pistols to Spotify.

Genre:

-

“[Gioia] uses the familiar scheme of cyclical rejuvenation through transformation as a mechanism to consider the whole history of music, from the sounds of the primordial world to electronic dance music today, in his latest and most ambitious book. . . . Smart but readable.”New York Times Book Review

-

“[A] sweeping study. . . . The author aims to subvert our ideas about music history. . . . Gioia challenges notions of progress based solely on aesthetic or stylistic innovation . . . characteriz[ing] music history as a cyclical power struggle with shifting battle lines.”Larry Blumenfeld, Wall Street Journal

-

“I can’t speak highly enough about Music: A Subversive History. . . . [Gioia] is always fun to read. . . . Gioia remains something of an outsider critic, convinced that the passion for destruction can be a creative passion.”Michael Dirda, Washington Post

-

“An entirely new way to look at how music evolved.”Rosa Inocencio Smith, The Atlantic

-

"A dauntingly ambitious, obsessively researched labor of cultural provocation."Robert Christgau, Los Angeles Times

-

“In the past, [Gioia has] written a series of acclaimed books about jazz, but Music: A Subversive History is by some distance the most wide-ranging and provocative thing he’s come up with.”Alexis Petridis, Guardian

-

“In carefully examining its ‘subversive’ side . . . Ted Gioia does much to convince us that music, far from being incidental to deeper political purposes or a convenient index of popular taste, is a profound ‘force of transformation and enchantment,’ intrinsic to human society.”New Criterion

-

“This book feels like the summation of a lifetime’s avid musical exploration and reading. It has an epic sweep and passionate engagement with the topic that carries one along irresistibly.”Telegraph

-

“Gioia asserts that music history generally shares the whitewashed stories of the assimilators. . . . Exhaustively researched.”Christian Science Monitor

-

“In the space of a sentence, Gioia has let even the most cautious prospective reader know he has a lovely light touch, a mischievous sense of humour, and a determinedly skewed take on how music has been chronicled over the past 2,000-odd years. The highlights are too many to list. . . . He knows how to tell a story in a way that will keep people reading.”Times Literary Supplement

-

“Mr. Gioia’s alternative history of music is extraordinary, groundbreaking, and bone-chillingly real.”Washington Times

-

“Ted Gioia’s Music: A Subversive History is one of the most important and welcome books I’ve encountered in the last decade. If ever there were a book the world sorely needed, it’s Gioia’s.”Buffalo News

-

“Scintillating. . . . Gioia is writing about evolution and magic—this is a music history that synthesizes both Darwin and Frazer, and, at least in terms of writing for a general audience, is the first to do so. We need this story.”Brooklyn Rail

-

“Music is Gioia’s magnum opus, an inventive and original work that spans 4,000 years. . . . Throughout this vital book, Gioia shows that music is still a disruptive force.”DownBeat

-

“There is so much rich history in this book; so many interesting and startling facts and stories.”Syncopated Times

-

“Invigorating.”Pop Matters

-

“Marvelous.”Marc Myers, Jazz Wax

-

“Essential.”Jacksonville Journal-Courier

-

“In describing the kinds of music that existed throughout history, [Gioia] treats topics that have long been suppressed or ignored by historians who crave respectability, topics such as magic, sexuality, and violence. . . . As a writer and thinker he is compelling and thought provoking.”Choice

-

“Gioia takes a look at the underside of music history, teasing out the episodes of sex, violence, and rebellion out of which music developed.”No Depression

-

“In this excellent history, music critic Gioia (How to Listen to Jazz) dazzles with tales of how music grew out of violence, sex, and rebellion. . . . Gioia’s richly told narrative provides fresh insights into the history of music."Publishers Weekly, starred review

-

"Gioia draws on social science research into the past and present to forge a sweeping and enthralling account of music as an agency of human change."Booklist, starred review

-

“Gioia’s argument is persuasive and offers a wealth of possibilities for further exploration.”Library Journal

-

“A revisionist history highlights music’s connections to violence, disruption, and power. In a sweeping survey that begins in ‘pre-human natural soundscapes,’ music historian Gioia (How To Listen to Jazz, 2016, etc.) examines changes and innovation in music, arguing vigorously that the music produced by ‘peasants and plebeians, slaves and bohemians, renegades and outcasts’ reflected and influenced social, cultural, and political life. . . . A bold, fresh, and informative chronicle of music’s evolution and cultural meaning.”Kirkus

-

"Gioia's sprawling and deeply interesting history of music defies all stereotypes of music scholarship. This is rich work that provokes many fascinating questions. Scientists and humanists alike will find plenty to disagree with, but isn't that the point? 'A subversive history,' indeed."Samuel Mehr, Director, The Music Lab, Harvard University

-

“In this meticulously researched yet thoroughly page-turning book, Gioia argues for the universality of music from all cultures and eras. Subversives from Sappho to Mozart and Charlie Parker are given new perspective—as is the role of the church and other arts-shaping institutions. Music of emotion is looked at alongside the music of political power in a fascinating way by a master writer and critical thinker. This is a must-read for those of us for whom music has a central role in our daily lives.”Fred Hersch, pianist and composer, and author of Good Things Happen Slowly: A Life In and Out of Jazz

-

“As a fan of ‘big histories’ that sweep through space and time, I gobbled this one like candy as I found myself astounded by some idea, some fact, some source, some dots connected into a fast-reading big picture that takes in Roman pantomime riots, Occitan troubadours, churchbells, blues, Afrofuturism, surveillance capitalism, and much more. A must for music heads.”Ned Sublette, author of Cuba and Its Music and The World That Made New Orleans

-

"One of the most perceptive writers on music has cut a wide swath down the path of history, illuminating details often left in the shadows and broadening our understanding of all things sonic. Gioia vividly points out that the wheels of cultural advancement are often turned by the countless unsung heroes of inventiveness. A mind opening and totally engaging read!"Terry Riley

- On Sale

- Apr 20, 2021

- Page Count

- 528 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541644373

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use