Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

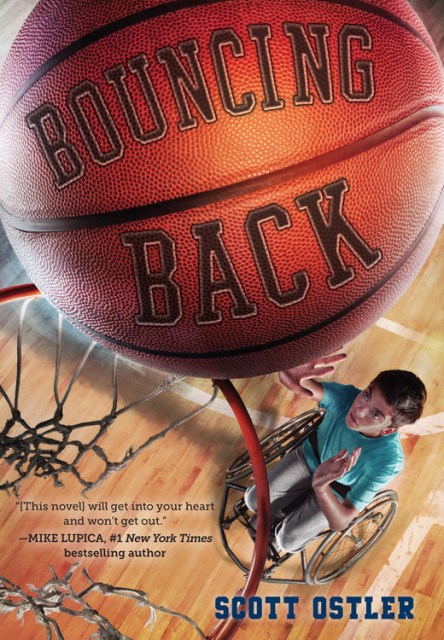

Bouncing Back

Contributors

By Scott Ostler

Formats and Prices

Price

$7.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $7.99 $11.99 CAD

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.98

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 13, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Back in his old basketball league, before the car accident, thirteen-year-old Carlos Cooper owned the court, sprinting and jumping and lighting up the scoreboard as his opponents (and teammates) watched in amazement. But now, Carlos feels completely out of his league on his new wheelchair basketball team, the Rollin’ Rats. After all, how can he make a layup when he’s still struggling to learn how to dribble?

But when the city’s crooked mayor threatens to tear down the Rollin’ Rats’ gym, Carlos realizes that he can’t stay on the sidelines forever. Because without a gym, the team can’t practice, and if they can’t practice, they can kiss their state tournament dreams goodbye. If Carlos is going to learn what it truly means to be part of a team and help his new friends save their season, he’ll have to either go all-in . . . or get out.

-

Praise for Bouncing Back:Mitch Albom, #1 New York Times bestselling author; Sports Columnist, Detroit Free Press; panelist, ESPN's The Sports Reporters

"A wonderful story of friendship and the unique ability of kids to overcome a challenge. Inspiring for young athletes and non-athletes alike." -

"My old friend Scott Ostler has always written a sports column informed by humor and heart. Now he gives us a novel about a boy, and his teammates, who will get into your heart and won't get out."Mike Lupica, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Heat and Travel Team

-

* "The multi-tiered plot moves quickly, the characters are engaging, and the wheelchair basketball is a unique premise, but the real draw in this debut novel from sportswriter Ostler are the vivid descriptions of basketball action. Of equal interest to boys and girls, this strikes just the right notes about teamwork, friendship, and acceptance."Booklist, starred review

-

"Enjoyable.... Perfect for middle grade fans of Mike Lupica."School Library Journal

-

"A sports story that's as heartwarming as it is action-packed."Kirkus Reviews

- On Sale

- Oct 13, 2020

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316524766

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use