Promotion

Sign up for our newsletters to receive 20% off! Shop now. Exclusions apply.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

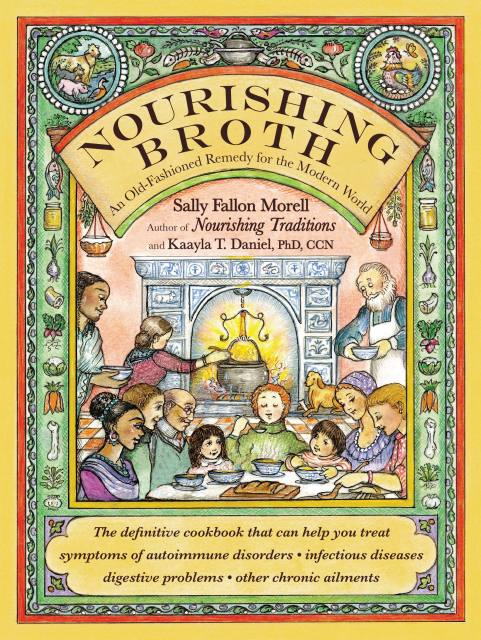

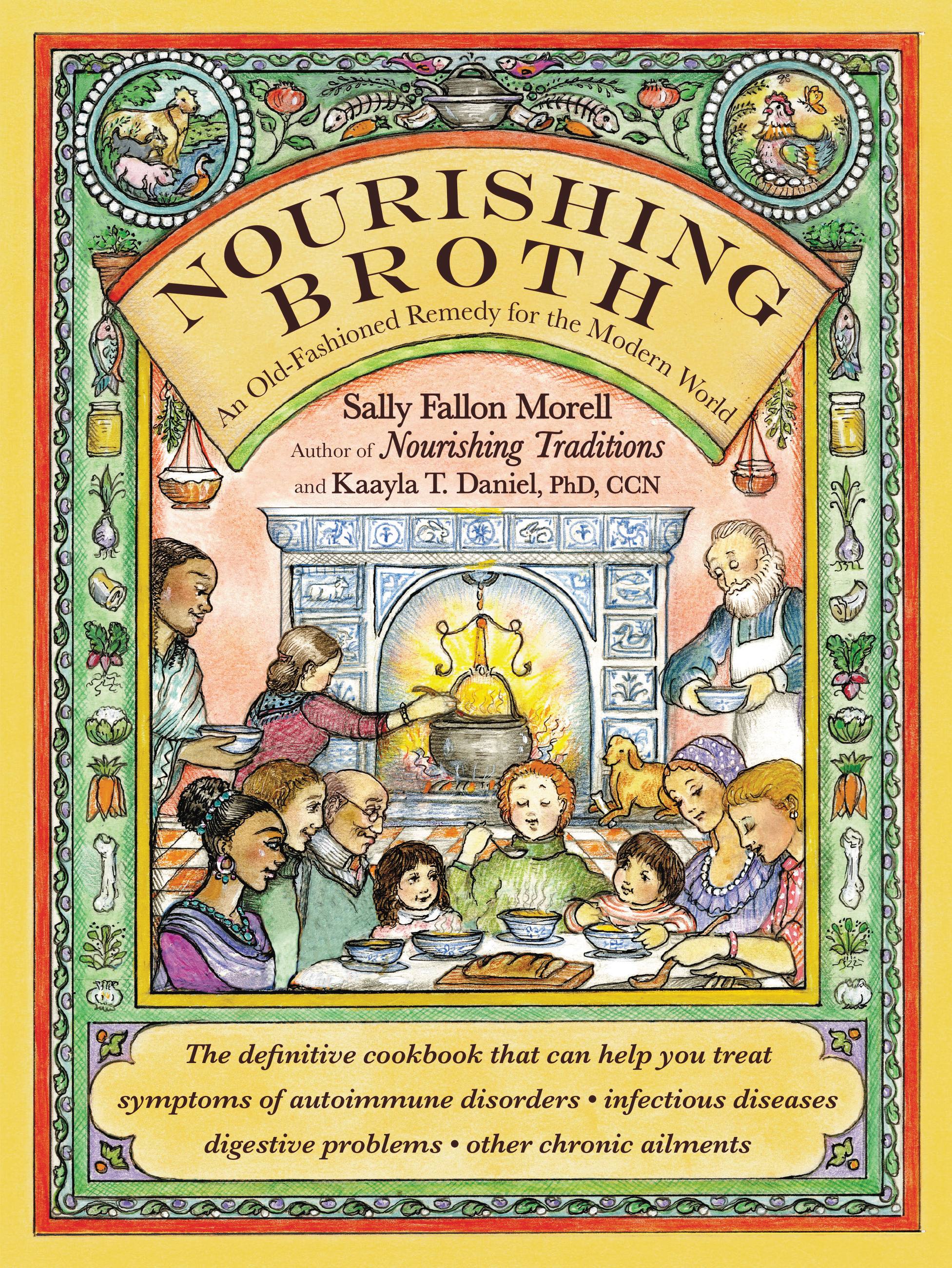

Nourishing Broth

An Old-Fashioned Remedy for the Modern World

Contributors

By Kaayla T. Daniel

Formats and Prices

Prices

- Sale Price $2.99

- Regular Price $13.99

- Discount (79% off)

Prices

- Sale Price $2.99 CAD

- Regular Price $17.99 CAD

- Discount (83% off)

Format

Format:

- ebook $2.99 $2.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 30, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Nourishing Broth:

An Old-Fashioned Remedy for the Modern World

Nourishing Traditions examines where the modern food industry has hurt our nutrition and health through over-processed foods and fears of animal fats. Nourishing Broth will continue the look at the culinary practices of our ancestors, and it will explain the immense health benefits of homemade bone broth due to the gelatin and collagen that is present in real bone broth (vs. broth made from powders).

Nourishing Broth will explore the science behind broth’s unique combination of amino acids, minerals and cartilage compounds. Some of the benefits of such broth are: quick recovery from illness and surgery, the healing of pain and inflammation, increased energy from better digestion, lessening of allergies, recovery from Crohn’s disease and a lessening of eating disorders because the fully balanced nutritional program lessens the cravings which make most diets fail. Diseases that bone broth can help heal are: Osteoarthritis, Osteoporosis, Psoriasis, Infectious Disease, digestive disorders, even Cancer, and it can help our skin and bones stay young.

In addition, the book will serve as a handbook for various techniques for making broths-from simple chicken broth to rich, clear consomme, to shrimp shell stock. A variety of interesting stock-based recipes for breakfast, lunch and dinner from throughout the world will complete the collection and help everyone get more nutrition in their diet.

- On Sale

- Sep 30, 2014

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Life & Style

- ISBN-13

- 9781455529230

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use