Promotion

Use code FALL24 for 20% off sitewide!

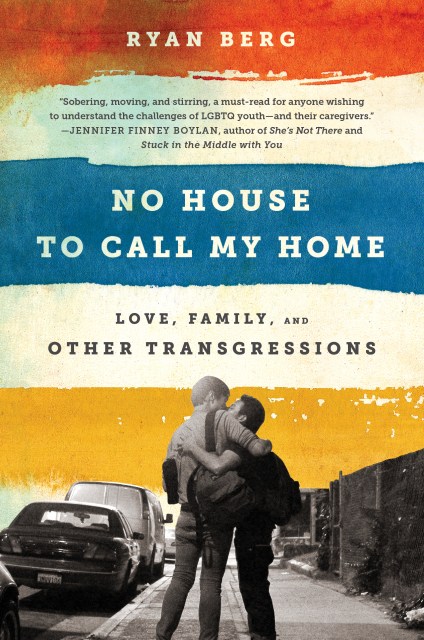

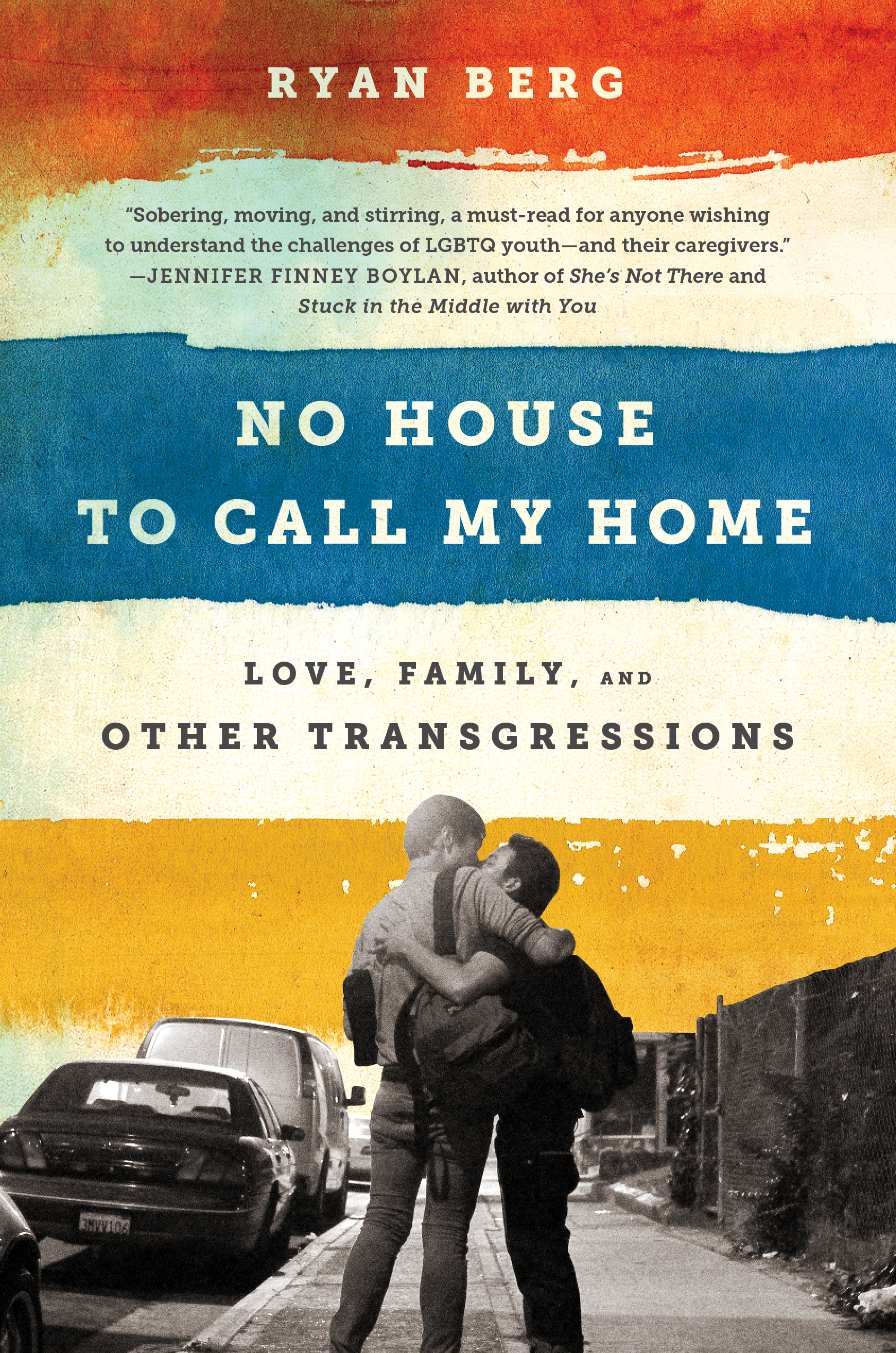

No House to Call My Home

Love, Family, and Other Transgressions

Contributors

By Ryan Berg

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $11.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 25, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In this lyrical debut, Ryan Berg immerses readers in the gritty, dangerous, and shockingly underreported world of homeless LGBTQ teens in New York. As a caseworker in a group home for disowned LGBTQ teenagers, Berg witnessed the struggles, fears, and ambitions of these disconnected youth as they resisted the pull of the street, tottering between destruction and survival.

Focusing on the lives and loves of eight unforgettable youth, No House to Call My Home traces their efforts to break away from dangerous sex work and cycles of drug and alcohol abuse, and, in the process, to heal from years of trauma. From Bella's fervent desire for stability to Christina's irrepressible dreams of stardom to Benny's continuing efforts to find someone to love him, Berg uncovers the real lives behind the harrowing statistics: over 4,000 youth are homeless in New York City — 43 percent of them identify as LGBTQ.

Through these stories, Berg compels us to rethink the way we define privilege, identity, love, and family. Beyond the tears, bluster, and bravado, he reveals the force that allows them to carry on — the irrepressible hope of youth.

-

"In No House to Call My Home Berg has given us an antidote to the numbness that comes with reading the statistics on homeless queer youth in America. He's given us their stories. In harrowing, vivid detail, he shows us, through his own experience of working with them, the lives of these young people of color as they struggle through the neglect of adults, the indifference of bureaucracies, and the harsh realities of fending for themselves in a cold world. Again and again, what they are denied is dignity. Which is what this book tries in its own way to give them back, and which is what any social cause requires to initiate lasting change—the opening of empathy." —Adam Haslett, National Book Award Finalist and author of Union Atlantic

"Ryan Berg opens a window into the troubled, often ignored world of New York City's foster care system, and by extension, America. No House to Call My Home is an important work that will be a revelation for many." —Saïd Sayrafiezadeh, author of Brief Encounters With the Enemy and When Skateboards Will Be Free -

"In No House to Call My Home Ryan Berg takes us into the New York foster care system—where he worked for two years as a residential counselor in a group home for LGBTQ youth of color—and gives us, along the way, an earnest, heartfelt, and deeply compassionate portrait of that most fundamental of human needs: to be loved unconditionally. Berg is a brave and clear-eyed writer, and this profoundly important book should be required reading for anyone wishing to be a better ally—or, for that matter, for anyone wishing to be a better human being." —Lacy M. Johnson, National Book Critics Circle Award Finalist and author of The Other Side

-

"Ryan Berg's No House to Call My Home takes readers inside the New York State foster care system, where LGBTQ youth who have been abandoned or abused are housed in order to keep them off the streets and out of harm. Residential counselors advise and advocate for these kids, helping them to negotiate institutional red tape, visits with their real families, education, employment and recovery. Berg's chronicle of the lives of the young residents at the 401 and Keap Street shows how much adversity they face and how much strength they draw from one another. These kids are smart, resourceful, brave and fierce. But they are also kids. No House to Call My Home is a call for greater understanding, support and advocacy for these children struggling to stand on their own as they 'age out' of the system and enter adulthood. Challenge and change are the daily currency for them. How are they to succeed with so many obstacles? This book offers suggestions and hope.” —D. A. Powell, author of Useless Landscape, or A Guide for Boys and Chronic

-

"Sometimes we don't understand the life we find ourselves in the midst of living. Sometimes our longing for home can drive us toward oblivion. Sometimes the best we can do is to create who we have to be in order to get what we need. Sometimes, by immersing ourselves in something larger than ourselves, we can discover who we are. In this moving and clear-eyed account, Ryan Berg reminds us that this moment is more precious than we think, and that sometimes the best we can do is to love each other (damn it). —Nick Flynn, bestselling author of Another Bullshit Night in Suck City

"Managing to be both journalistic and novelistic, Berg provides intimate portraits of LGBTQ youths who are left to fend for themselves. Compelling from the first page No House to Call My Home is unflinchingly candid in its portrayal of a broken system, and a broken society where abandoning youths is overlooked. Berg allows the brilliance and resilience of these young people to shine bright. The adversity they face should enrage you; their courage and grace will move you.” —Richard Blanco, author of The Prince of los Cocuyos: A Miami Childhood -

"What do we owe our children? Who will keep the company of those children forgotten or lost? Ryan Berg ventures an unforgettable tribute to the youth he encountered in the New York foster care system. Zooming in on LGBT youth of color and the forgotten stories of homeless youth in America, No House to Call My Home recalls, remembers, recovers the lives and bodies and truths of the children we leave behind. Home is a story told by children who had to write the fiction of a family for themselves in order to survive. All those voices, in these pages, becoming song." —Lidia Yuknavitch, author of The Chronology of Water: A Memoir and The Small Backs of Children: A Novel

-

“An important and revelatory read.” —The Rumpus

“Just as there is a school-to-prison pipeline in this country, so too, this grim report reveals, is there a home-to-homeless paradigm for many young people. Life on the streets is tough. It is tougher still for LGBT—or, as writer, activist, and former counselor Berg would have it, LGBTQ, the last element meaning "questioning"—kids, who constitute as much as 40 percent of the population of young homeless people... Berg's portraits are arresting… His fraught encounters with individuals become universal, offering a touch of hope…Particularly important for caseworkers and social service specialists, who, by Berg's account, are likely to encounter more young people in the LGBTQ population in the near future.” —Kirkus Reviews

“Ryan's Berg's No House to Call My Home is a searing, harrowing, and ultimately inspiring story of the struggles all too many transgender people experience. Berg's heroes, denied the common decency of house and home, nonetheless refuse to surrender their humanity. Sobering, moving and stirring, No House to Call My Home is a must read for anyone wishing to understand the challenges of transgender men and women—and their caregivers." —Jennifer Finney Boylan, author of She's Not There and Stuck In The Middle With You

- On Sale

- Aug 25, 2015

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568585109

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use