Promotion

Sign up for our newsletters to receive 20% off! Shop now. Exclusions apply.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

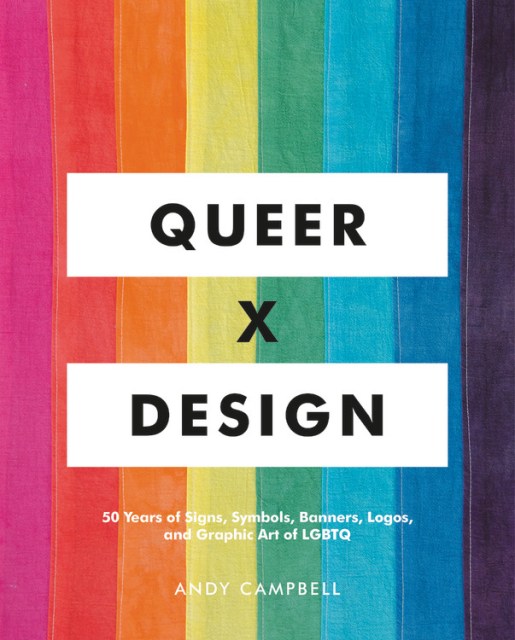

Queer X Design

50 Years of Signs, Symbols, Banners, Logos, and Graphic Art of LGBTQ

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.00Price

$34.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $34.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 7, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The first-ever illustrated history of the iconic designs, symbols, and graphic art representing more than 5 decades of LGBTQ pride and activism.

Beginning with pre-liberation and the years before the Stonewall uprising, spanning across the 1970s and 1980s and through to the new millennium, Queer X Design celebrates the inventive and subversive designs that have powered the resilient and ever-evolving LGBTQ movement.

The diversity and inclusivity of these pages is as inspiring as it is important, both in terms of the objects represented as well as in the array of creators; from buttons worn to protest Anita Bryant, to the original ‘The Future is Female’ and ‘Lavender Menace’ t-shirt; from the logos of Pleasure Chest and GLAAD, to the poster for Cheryl Dunye’s queer classic The Watermelon Woman; from Gilbert Baker’s iconic rainbow flag, to the quite laments of the AIDS quilt and the impassioned rage conveyed in ACT-UP and Gran Fury ephemera.

More than just an accessible history book, Queer X Design tells the story of queerness as something intangible, uplifting, and indestructible. Found among these pages is sorrow, loss, and struggle; an affective selection that queer designers and artists harnessed to bring about political and societal change. But here is also: joy, hope, love, and the enduring fight for free expression and representation. Queer X Design is the potent, inspiring, and colorful visual history of activism and pride.

-

"Since Queer X Design was published, it has become a touchstone for the modern history of the graphic design that accompanies queer movements."BookRiot

-

"Sometimes, a rebellion begins with a rebrand. In Queer X Design, the professor Andy Campbell weaves a telling visual tapestry of an emerging L.G.B.T.Q. language and identity."The New York Times

-

"This illuminating compendium by art historian and curator Andy Campbell is a deep dive into more than 50 years of the extraordinary art and design that came to represent the LGBTQ movement...Queer X Design is a must-read for anyone interested in the convergence of design, politics, and activism."Metropolis Magazine

-

"A beautifully bound, well-researched book that draws a lineage of LGBTQ designs richer than a thousand rainbow Ralph Lauren polos. Campbell's book details an uncut LGBTQ artistry, spanning digital, print, paint, and even ink n' skin work (check out the Phil Sparrow's Tattoo Flash for that good stuff) -- tracing back to the days of pre-liberation and upward into the 21st century."The Austin Chronicle

-

"An entertaining, insightful, beautifully illustrated book that explains and celebrates the role of LGBTQ graphic design, and designers, since the Stonewall uprising in 1969 -- a sort of history of LGBTQ life and activism told through our symbols... [Campbell's] writing is insightful and entertaining and always interesting."A&U Magazine

-

"A pretty comprehensive illustrated history of the gay rights movement and how it's changed over the years.... Discover the stories behind some of the most memorable symbols of the past five decades."HeSaid Magazine

-

"[Queer X Design] is an anthology of our trek from invisibility into Pride and beyond. It's a fascinating record that contains images that also predate the Stonewall rebellion by more than a quarter century... Between the covers of Queer X Design, you'll find photos that delight, artwork that seethes with rage, and images that have united the LGBTQ community in victories and setbacks throughout the struggle for equality."Metrosource

-

"An empowering visual history of the iconic symbols and designs that defined many eras of the LGBTQ movement."The Globe and Mail

-

"Queer X Design highlights and celebrates the many inventive and subversive designs that have helped drive the LGBTQ movement over the years...it's an inspiring and colourful visual history of design harnessed to bring about political and societal change."CreativeBloq

-

"A big, bold, and inspiring collection of the visual imagery that both represented and shaped the identity of the LGBTQ movement."The Advocate

-

"For the first time, a colorful, visual collection coalesces the iconic posters, symbols and graphic designs that have defined 50 years of LGBTQ pride and activism. By decade, Andy Campbell's Queer X Design traces the lineage of lGBTQ artistry through pre-Stonewall to the present day."Azure Magazine

- On Sale

- May 7, 2019

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780762467853

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use