Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

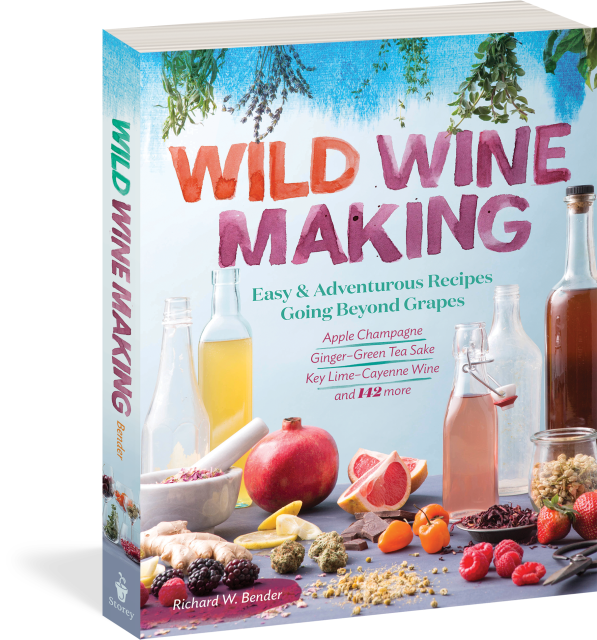

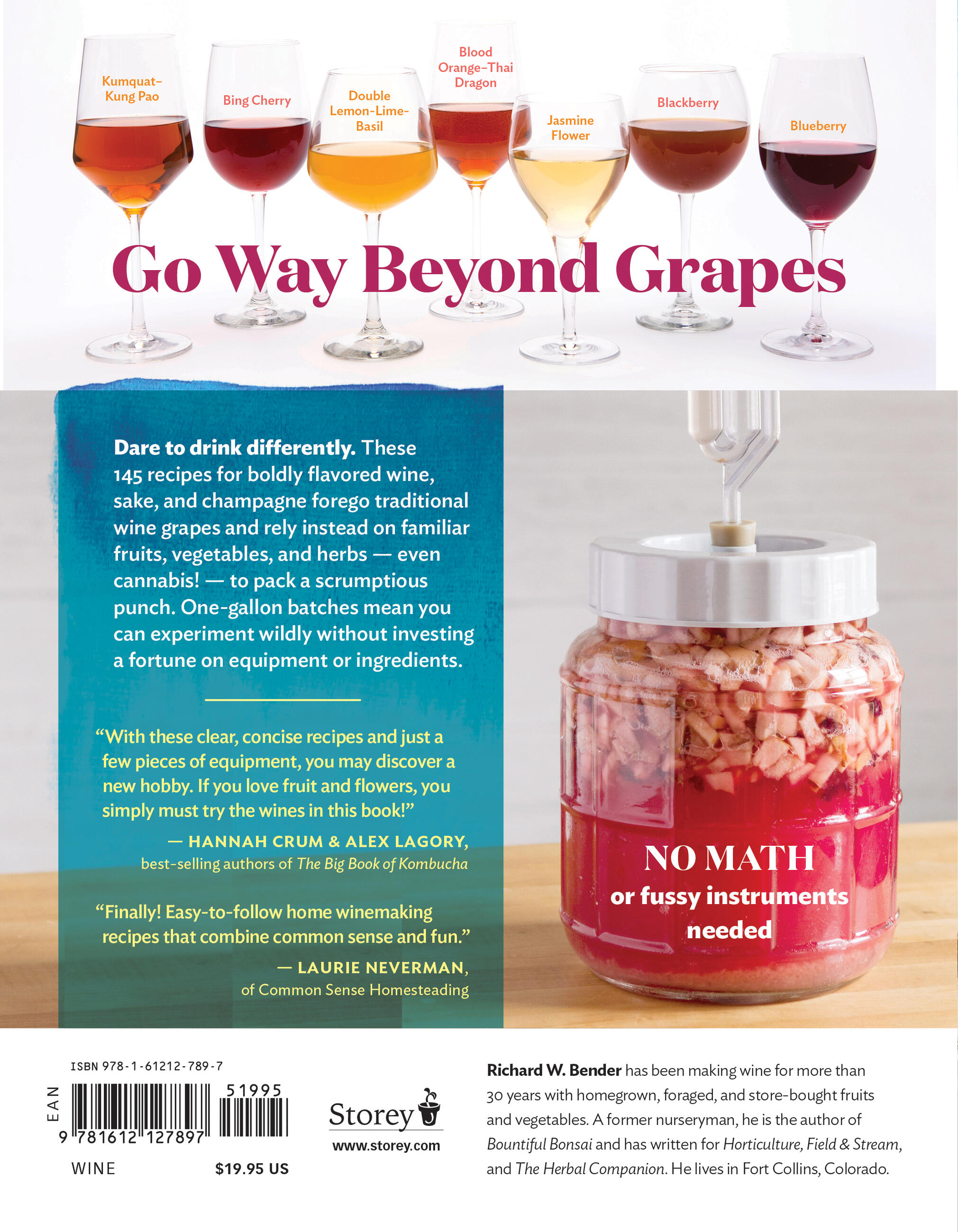

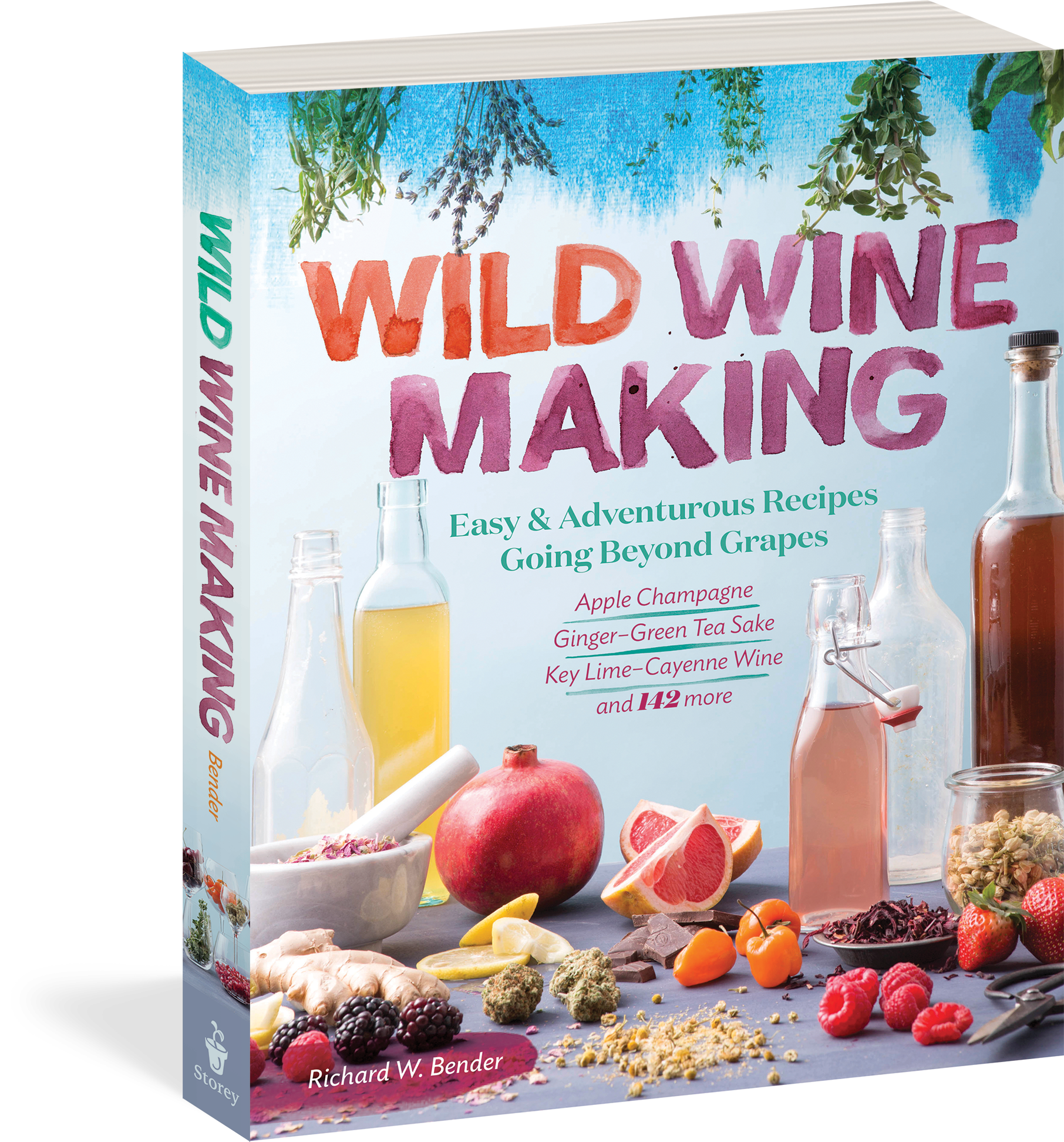

Wild Winemaking

Easy & Adventurous Recipes Going Beyond Grapes, Including Apple Champagne, Ginger–Green Tea Sake, Key Lime–Cayenne Wine, and 142 More

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 20, 2018

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Storey

- ISBN-13

- 9781612127897

Price

$19.95Price

$24.95 CADFormat

Format:

Trade Paperback $19.95 $24.95 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 20, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

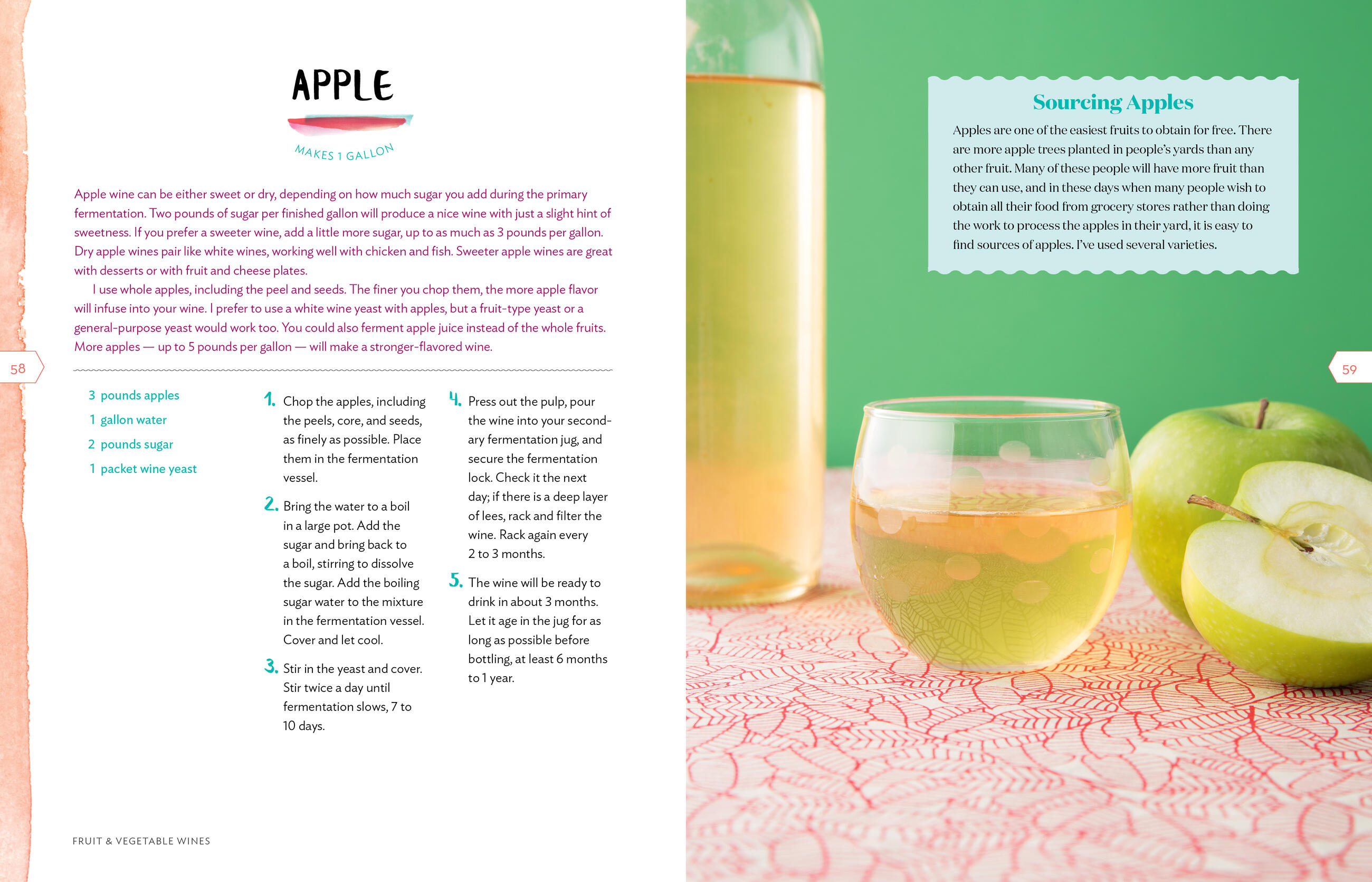

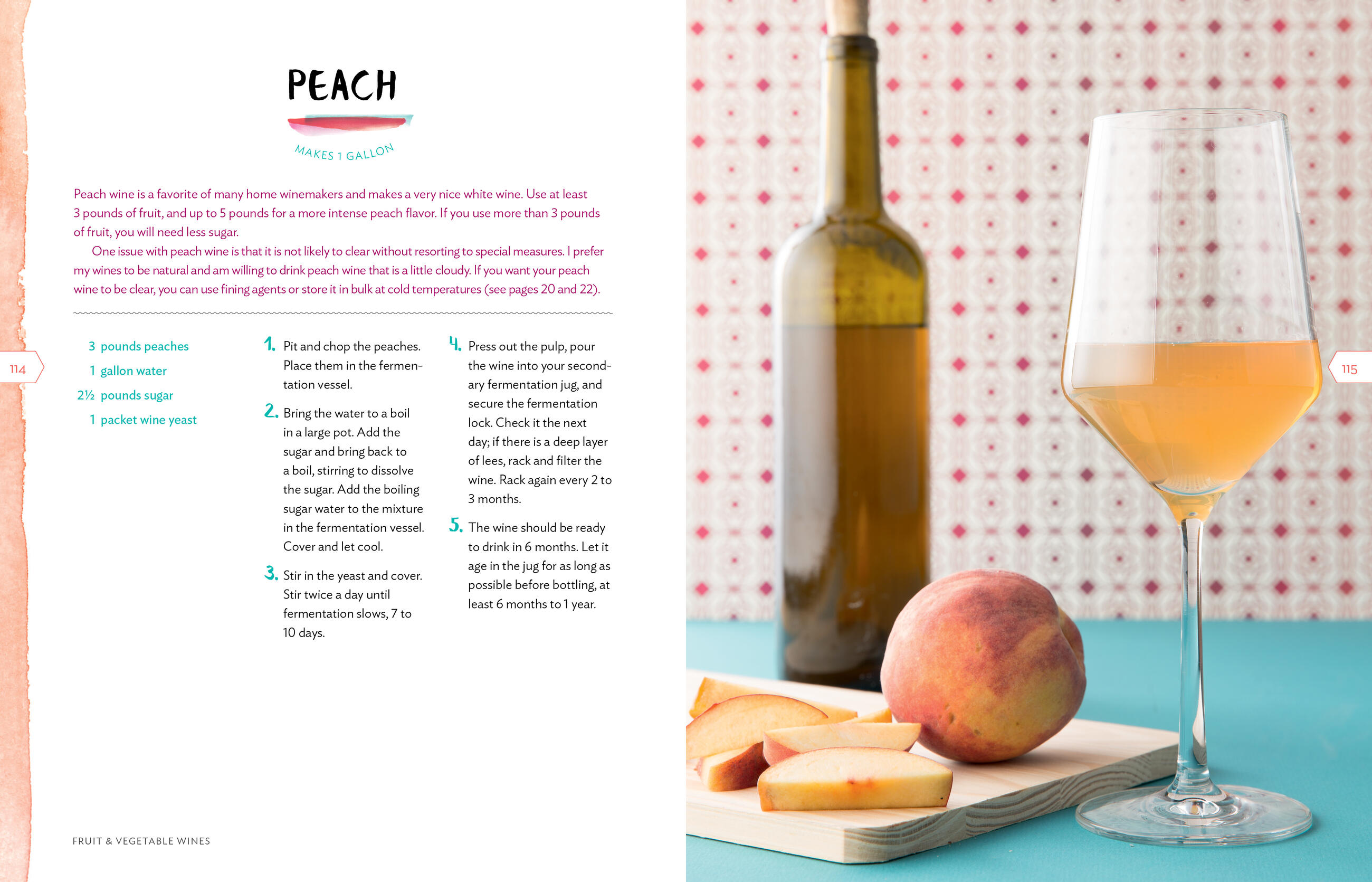

Making wine at home just got more fun, and easier, with Richard Bender’s experiments. Whether you’re new to winemaking or a seasoned pro, you’ll find this innovative manual accessible, thanks to its focus on small batches that require minimal equipment and use an unexpected range of readily available fruits, vegetables, flowers, and herbs. The ingredient list is irresistibly curious. How about banana wine or dark chocolate peach? Plum champagne or sweet potato saké? Chamomile, sweet basil, blood orange Thai dragon, kumquat cayenne, and even cannabis rhubarb wines have earned a place in Bender’s flavor collection. Go ahead, give it a try.

-

“Finally! Easy-to-follow home winemaking recipes that combine common sense and fun.” — Laurie Neverman, of Common Sense Homesteading

“A beautiful ode to the magical meeting of the harvest and friendly microbes. If you have tried your hand at fermentation and love fruit and flowers, you must try the wines in this book!” — Hannah Crum Alex LaGory, best-selling authors of The Big Book of Kombucha and founders of KombuchaKamp.com