Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

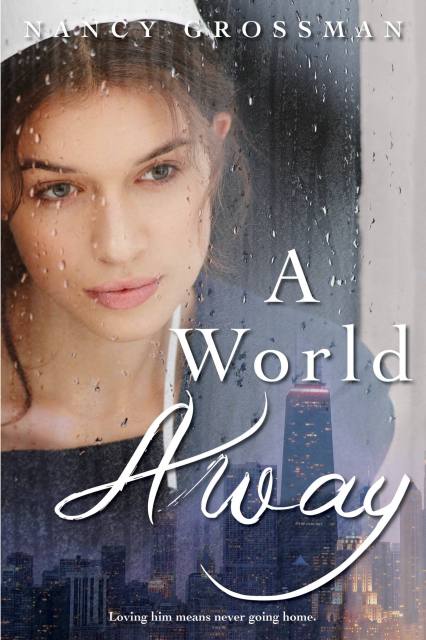

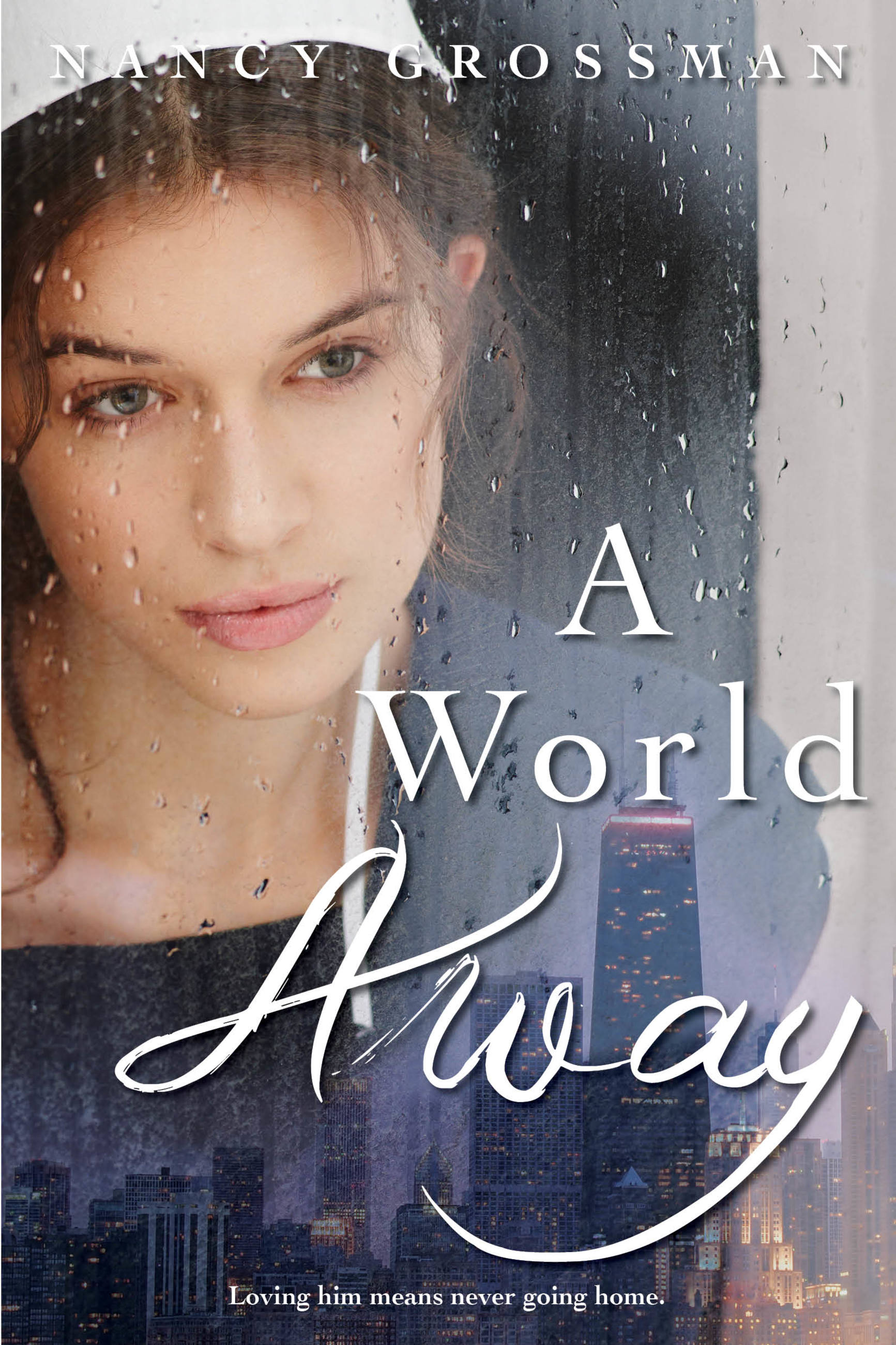

A World Away

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$7.99Price

$9.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $7.99 $9.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 17, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Sixteen-year-old Eliza Miller has never made a phone call, never tried on a pair of jeans, never sat in a darkened theater waiting for a movie to start. She’s never even talked to someone her age who isn’t Amish, like her.

A summer of good-byes.

When she leaves her close-knit family to spend the summer as a nanny in suburban Chicago, a part of her can’t wait to leave behind everything she knows. She can’t imagine the secrets she will uncover, the friends she will make, the surprises and temptations of a way of life so different from her own.

A summer of impossible choice.

Every minute Eliza spends with her new friend Josh feels as good as listening to music for the first time, and she wonders whether there might be a place for her in his world. But as summer wanes, she misses the people she has left behind, and the Plain life she once took for granted. Eliza will have to decide for herself where she belongs. Whichever choice she makes, she knows she will lose someone she loves.

- On Sale

- Jul 17, 2012

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781423178095

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use