By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

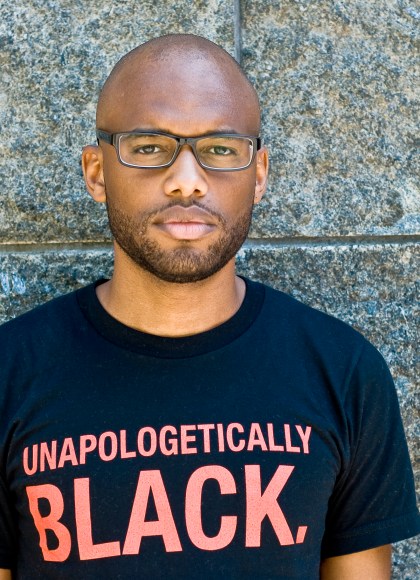

Stakes Is High

Life After the American Dream

Contributors

Read by Mychal Denzel Smith

Formats and Prices

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $14.99 $18.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 15, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Brave, clear-eyed, and passionate, Stakes Is High is the book we need to guide us past crisis mode and through an uncertain future.

The events of the past decade have forced us to reckon with who we are and who we want to be. We have been invested in a set of beliefs about our American identity: our exceptionalism, the inevitable rightness of our path, the promise that hard work and determination will carry us to freedom. But in Stakes Is High, Mychal Denzel Smith confronts the shortcomings of these stories — and with the American Dream itself — and calls on us to live up to the principles we profess but fail to realize.

The events of the past decade have forced us to reckon with who we are and who we want to be. We have been invested in a set of beliefs about our American identity: our exceptionalism, the inevitable rightness of our path, the promise that hard work and determination will carry us to freedom. But in Stakes Is High, Mychal Denzel Smith confronts the shortcomings of these stories — and with the American Dream itself — and calls on us to live up to the principles we profess but fail to realize.

In a series of incisive essays, Smith exposes the stark contradictions at the heart of American life, holding all of us, individually and as a nation, to account. We’ve gotten used to looking away, but the fissures and casual violence of institutional oppression are ever-present.

There is a future that is not as grim as our past. In this profound work, Smith helps us envision it with care, honesty, and imagination.

-

"[Smith] is sharply self-aware, and he would seem to expect his reader to approach his fine-honed argument with the same seriousness. Doing so is well worth the effort. An urgent and provocative work that deserves the broadest possible audience."Kirkus Reviews, starred

-

"Slim, impactful....Stakes Is High is a polemic in the best sense of the word, holding up a mirror to America in the hope that a clear-eyed glimpse of its failings will assist in the never-ending struggle to bring about the righteous nation it has always aspired to be."Booklist, starred

-

"A clear-eyed and down-to-earth analysis of the broken foundation of the American Dream and how our culture can move past it....As the book's title and its author suggest: the stakes are high."TheGrio

-

"Smith's galvanizing rhetoric implores a commitment to honesty.... This passionate book is a plea for the U.S. to recognize the delusions casting it as an equal, just country and to see revolution as necessary."Shelf Awareness

-

"[Stakes Is High] is beautiful, grim, yet hopeful of a future in which we choose to act collectively and work together to create a new narrative of America."Electric Literature

-

"With searing vision and unwavering clarity, Mychal Denzel Smith dismantles our most enduring myths and dangerous national illusions. His argument is personal, intimate. It calls on us, line by line, to do the hard work of truthful living: to hold past and present, love and criticism, up in equal measure. Stakes Is High will undoubtedly prove to be one of the most important works of the decade; as social critique, as personal essay, as a master class in language. Keep it within arm's length; you'll be reaching for it long after you've read the last line."Téa Obreht, author of Inland

-

"Stakes Is High is Mychal Denzel Smith's gift to us. With compassion and intelligence, he shows us what justice is meant to be in America."Common

-

"Mychal Denzel Smith has written an emotional break-up letter with hope. In his meditations on the pillars of American life, Smith challenges us to accept our complicity in the systems that link our fortunes to our oppressions. It is elegantly written and lovingly argued."Tressie McMillan Cottom, author of Thick: And Other Essays

-

"I want this book in the hands of everyone it would affect, which is to say, those with power and those lacking power; those of every race and ethnicity who are affected by the United States government; those who have hope, those who do not, and those who are somewhere in between. Smith writes with urgency and brilliance, honing prose to a fine glimmer as he demonstrates, again and again, life after the American Dream."Esmé Weijun Wang, author of The Collected Schizophrenias

-

"Mychal Denzel Smith's Stakes is High is the book we need. It dismantles American lies and instead offers a truth that feels like fire. Smith moves from point to point with a brilliant agility founded on a deep understanding of our history. A truly spectacular book."Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, author of Friday Black

-

"Stakes Is High is that rare book written before the pandemic that predicts the American response to the pandemic and also provides a soulful, rigorous way out of the destruction. Mychal Denzel Smith is the rarest of tenacious writers who remind us that the only way into a dignified free future is backwards. And our refusal to go walk back together makes the stakes highest for the most vulnerable children of tomorrow."Kiese Laymon, author of Heavy: An American Memoir

-

"Nuanced, intimate, and sharp in its view of America's history and present, Mychal Denzel Smith's Stakes Is High offers a clear-eyed view of this nation's inequities, shortcomings, and self-deceptions. It's a beautifully written, timely and illuminating book."Rebecca Traister, author of Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women's Anger

-

"Stakes Is High is a passionate, urgent book, a personal account of a contemporary New York political education, and a call to confront the emergency with clarity and truthfulness about the history that brought us here."Hari Kunzru, author of White Tears

-

"From one of our country's clearest truth-tellers comes this collection detailing why we've arrived at this current moment and how we can move beyond it. Stakes Is High confronts the inherent failures of the American dream, the dangers and delusions of American empire, and helps us imagine ourselves into a more just future."Lisa Ko, author of The Leavers

-

"A fresh, modern, thrilling call for humanity to come together as well as a brilliant investigation into what it means to be an American. Stakes Is High is required reading."Jami Attenberg, author of All This Could Be Yours

-

"Stakes is High is a marvel, and each page shines with miraculously unfailing clarity and grace. I want this radiant book to be a common read for our entire troubled country."R.O. Kwon, author of The Incendiaries

- On Sale

- Sep 15, 2020

- Page Count

- 192 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549170034

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use