Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

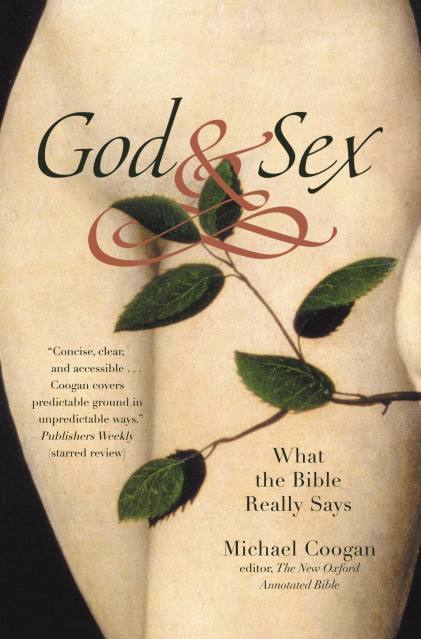

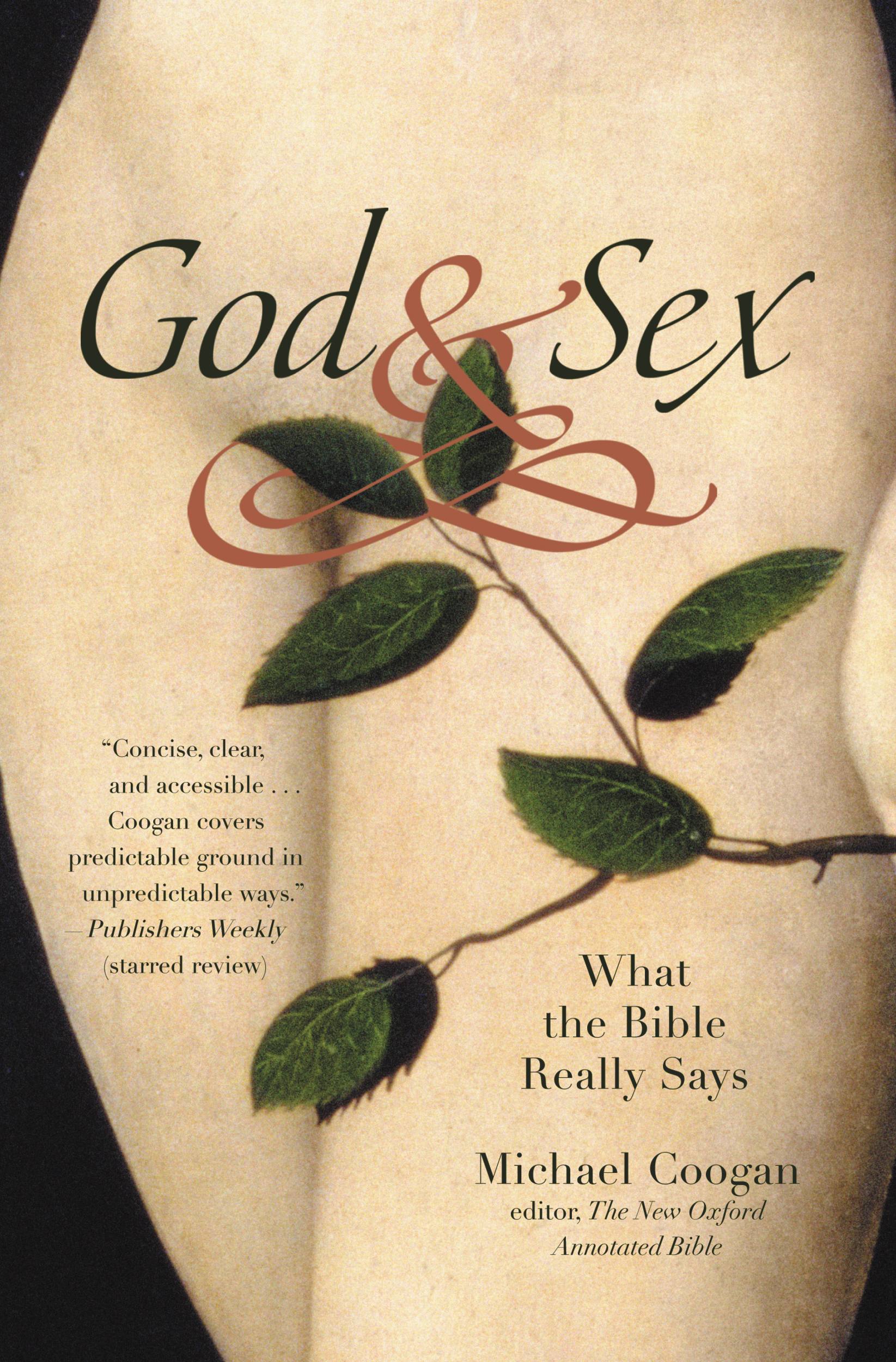

God and Sex

What the Bible Really Says

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 1, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

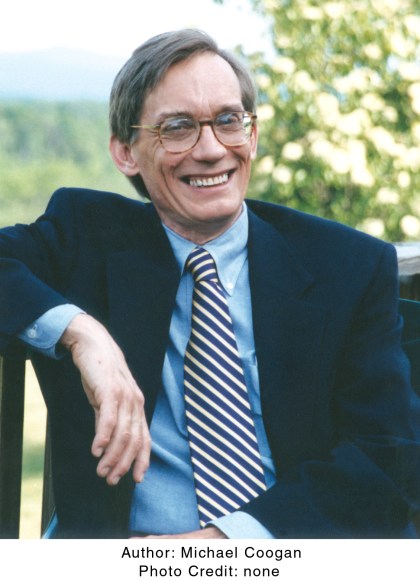

An examination of sex and the Bible by one of the leading biblical scholars in the United States.

For several decades, Michael Coogan's introductory course on the Old Testament has been a perennial favorite among students at Harvard University. In God and Sex, Coogan examines one of the most controversial aspects of the Hebrew Scripture: What the Old Testament really says about sex, and how contemporary understanding of those writings is frequently misunderstood or misrepresented. In the engaging and witty voice generations of students have appreciated, Coogan explores the language and social world of the Bible, showing how much innuendo and euphemism is at play, and illuminating the sexuality of biblical figures as well as God. By doing so, Coogan reveals the immense gap between popular use of Scripture and its original context. God and Sex is certain to provoke, entertain, and enlighten readers.

For several decades, Michael Coogan's introductory course on the Old Testament has been a perennial favorite among students at Harvard University. In God and Sex, Coogan examines one of the most controversial aspects of the Hebrew Scripture: What the Old Testament really says about sex, and how contemporary understanding of those writings is frequently misunderstood or misrepresented. In the engaging and witty voice generations of students have appreciated, Coogan explores the language and social world of the Bible, showing how much innuendo and euphemism is at play, and illuminating the sexuality of biblical figures as well as God. By doing so, Coogan reveals the immense gap between popular use of Scripture and its original context. God and Sex is certain to provoke, entertain, and enlighten readers.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 1, 2010

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9780446574136

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use