Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

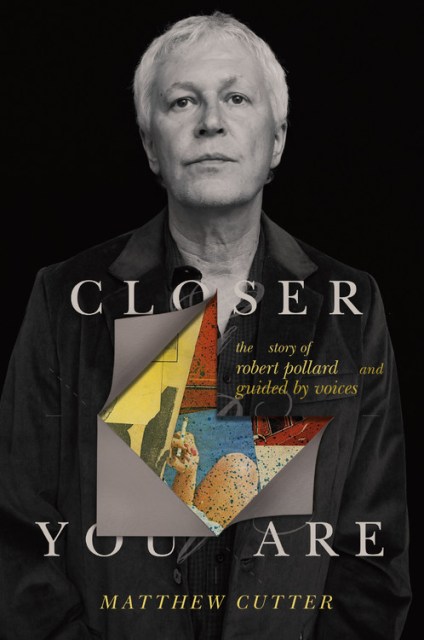

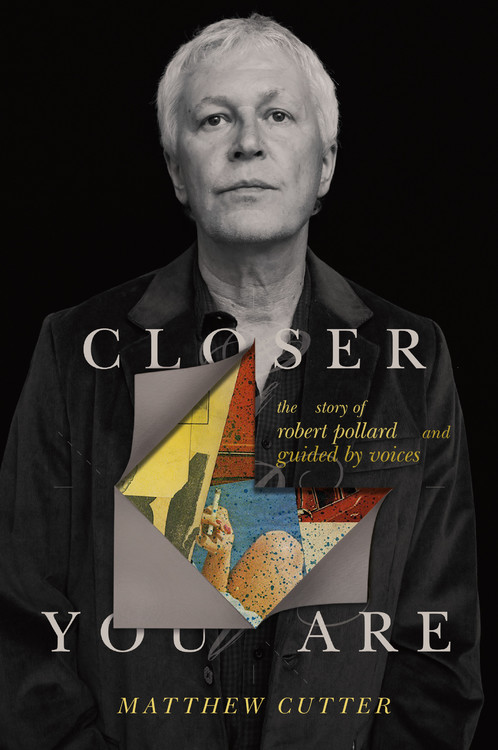

Closer You Are

The Story of Robert Pollard and Guided By Voices

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 21, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Robert Pollard has been a staple of the indie rock scene since the early ’80s, along with his band Guided By Voices. Pollard was a longtime grade school teacher who toiled endlessly on his music, finding success only after adopting a do-it-yourself approach, relying on lo-fi home recordings for much of his and his band’s career. A prolific artist, Pollard continues to churn out album after album, much to the acclaim of critics and his obsessive and devoted fans. But his story has never been faithfully told in its entirety. Until now.

Author Matthew Cutter is a longtime friend of Pollard and, with Pollard’s blessing, he’s set out to tell the whole, true story of Guided By Voices. Closer You Are is the first book to take an in-depth look at the man behind it all, with interviews conducted by the author with Pollard’s friends, family, and bandmates, along with unfettered access to Pollard himself and his extensive archives.

Robert Pollard has had an amazing and seemingly endless career in rock music, but he’s also established himself as a consummate artist who works on his own terms. Now fans can at long last learn the full story behind one of America’s greatest living songwriters.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 21, 2018

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306825767

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use