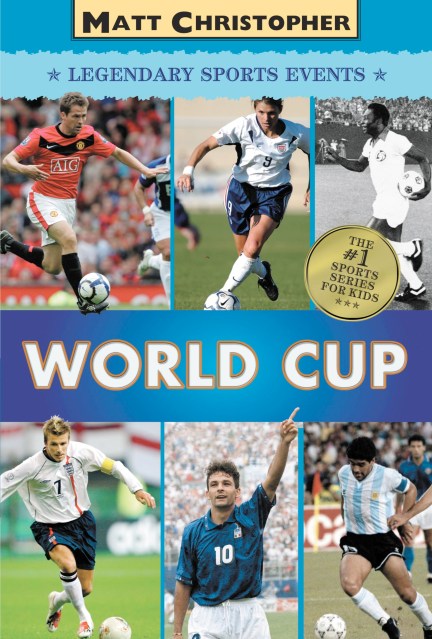

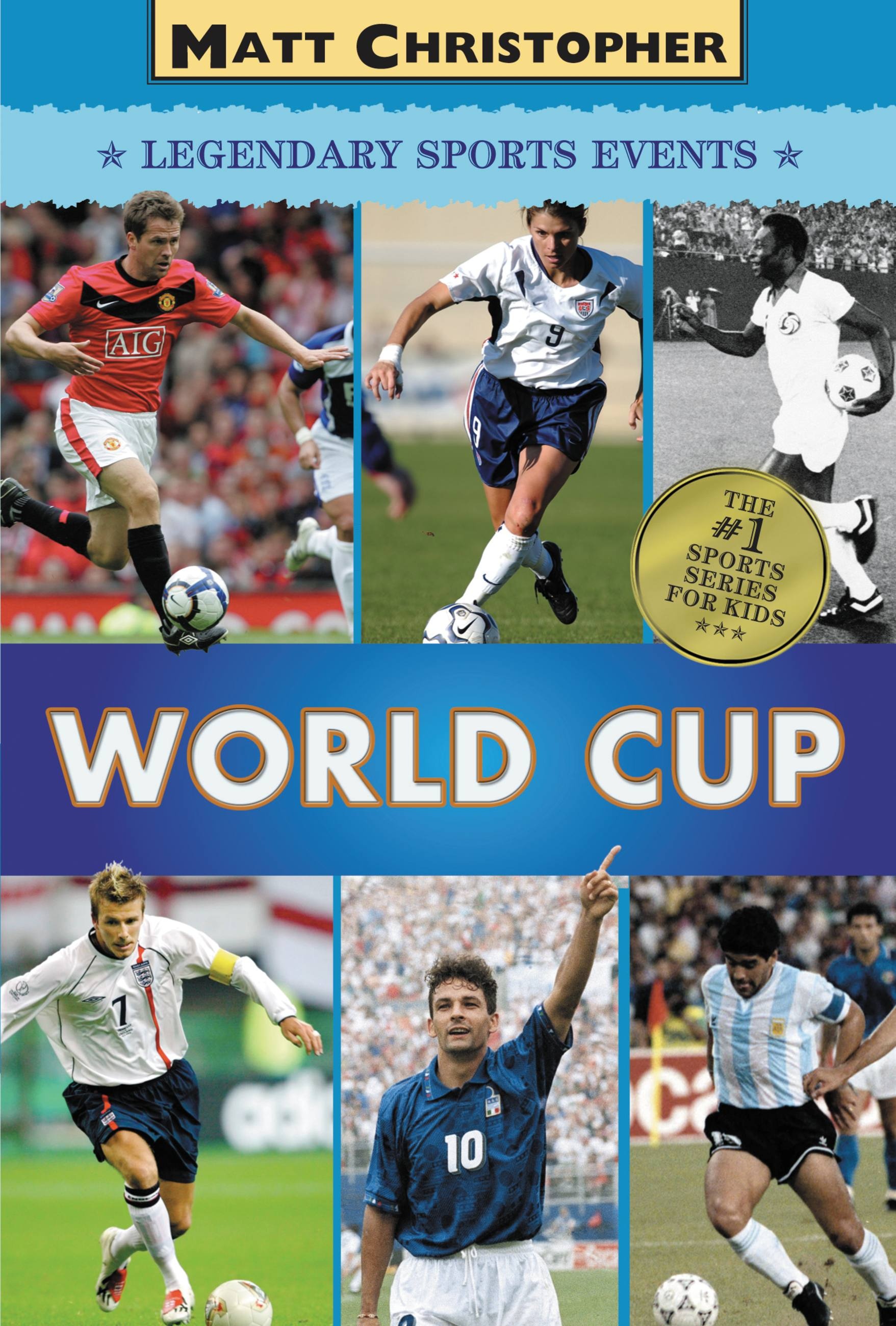

World Cup

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$3.99Price

$4.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $3.99 $4.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Audiobook CD (Unabridged) $12.98 $15.98 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 1, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Want to know who was behind the biggest surprise defeat of the 1950 tournament? It’s in here. Curious about what happened to the Jules Rimet trophy when it was in England? Turn to the chapter on World Cup 1966. Wondering what the term Total Football means? You’ll find the answer here — along with much, much more, including a bonus chapter on the Women’s World Cup and lists of winners, runners-up, and scores of past Cups. And because it all comes from Matt Christopher, young readers know they’re getting the best sports writing on the shelf.

- On Sale

- Jun 1, 2010

- Page Count

- 128 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316088572

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use