Promotion

Sign up for our newsletters to receive 20% off! Shop now. Exclusions apply.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

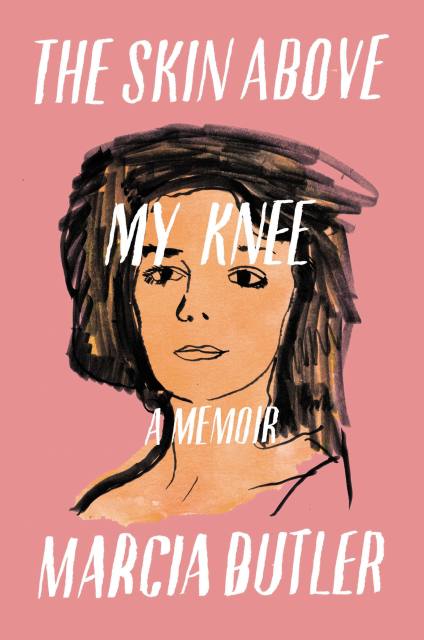

The Skin Above My Knee

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 21, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The unflinching story of a professional oboist who finds order and beauty in music as her personal life threatens to destroy her.

Music was everything for Marcia Butler. Growing up in an emotionally desolate home with an abusive father and a distant mother, she devoted herself to the discipline and rigor of the oboe, and quickly became a young prodigy on the rise in New York City’s competitive music scene.

But haunted by troubling childhood memories while balancing the challenges of a busy life as a working musician, Marcia succumbed to dangerous men, drugs and self-destruction. In her darkest moments, she asked the hardest question of all: Could music truly save her life?

A memoir of startling honesty and subtle, profound beauty, The Skin Above My Knee is the story of a woman finding strength in her creative gifts and artistic destiny. Filled with vivid portraits of 1970’s New York City, and fascinating insights into the intensity and precision necessary for a career in professional music, this is more than a narrative of a brilliant musician struggling to make it big in the big city. It is the story of a survivor.

One of 2017’s 35 over 35 One of the Washington Post‘s Top 10 Classical Music Moments of the Year

- On Sale

- Feb 21, 2017

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316392266

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use