By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

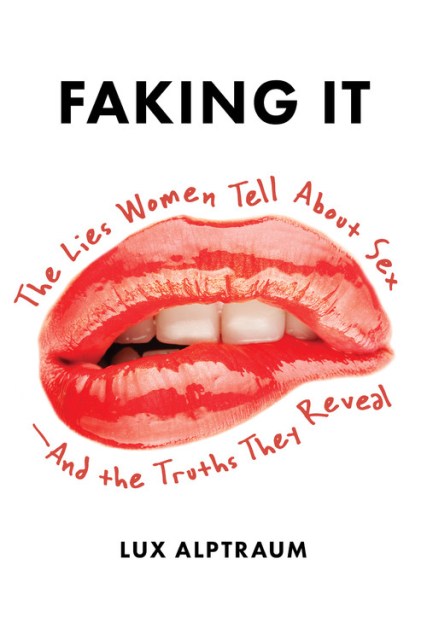

Faking It

The Lies Women Tell about Sex--And the Truths They Reveal

Contributors

By Lux Alptraum

Formats and Prices

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 6, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

When we talk about sex, we talk about women as mysterious, deceptive, and – above all – untrustworthy. Women lie about orgasms. Women lie about being virgins. Women lie about who got them pregnant, about whether they were raped, about how many people they’ve had sex with and what sort of experiences they’ve had – the list goes on and on. Over and over we’re reminded that, on dates, in relationships, and especially in the bedroom, women just aren’t telling the truth. But where does this assumption come from? Are women actually lying about sex, or does society just think we are?

In Faking It, Lux Alptraum tackles the topic of seemingly dishonest women; investigating whether women actually lie, and what social situations might encourage deceptions both great and small. Using her experience as a sex educator and former CEO of Fleshbot (the foremost blog on sexuality), first-hand interviews with sexuality experts and everyday women, Alptraum raises important questions: are lying women all that common – or is the idea of the dishonest woman a symptom of male paranoia? Are women trying to please men, or just avoid their anger? And what affect does all this dishonesty – whether real or imagined – have on women’s self-images, social status, and safety?

Through it all, Alptraum posits that even if women are lying, we’re doing it for very good reason — to protect ourselves (“My boyfriend will be here any minute,” to a creep who won’t go away, for one), and in situations where society has given us no other choice.

-

"Forthright, provocative, and studded with irony, Alptraum's incisive discussion calls for more flexibility, openness, conversation, and variety around sexual narratives and, most crucially, believing women."Publishers Weekly **starred review**

-

"Alptraum holds social codes, pop-culture narratives, and media myths up to the light to help readers understand why women internalize sexual shame-but also to encourage us to stop doing so."Bitch

-

"This book is a brilliant and necessary part of the conversation, and it cements Alptraum as one of our most essential contemporary voices on sex and gender."Carmen Maria Machado, author of Her Body and Other Parties

-

"Quite literally a revelation....Alptraum sets a cleansing fire to myths about sex, shame, and deception that have been hiding in plain sight for centuries."Andi Zeisler, author of We Were Feminists Once

-

"This is a mind blower of a read. A completely fresh perspective."Jenny Lumet, screenwriter, Rachel Getting Married

-

"Lux Alptraum is a fearless and frequently hilarious guide through the murky waters of 21st-century sexual politics, one who never settles for the easy answers. Faking It shows that in sex -- as in so much else -- what women do matters less than why they do it."Sady Doyle, author of Trainwreck

-

"Alptraum's work announces itself as an essential part of a vital conversation."Library Journal (starred review)

-

"Alptraum explores the persistence of a cultural narrative whose wide-ranging repercussions harm all humans. The book holds social codes, pop-culture narratives, and media myths up to the light to help readers understand why women internalize sexual shame-but also to encourage us to stop doing so."BUST

-

"Alptraum explores the way women tend to have very good reasons for the lies they tell and asks readers to think beyond snap moral judgments and take a look at the larger social traps women are put in that make them feel lying is necessary at all."Salon

- On Sale

- Nov 6, 2018

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580057653

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use