Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

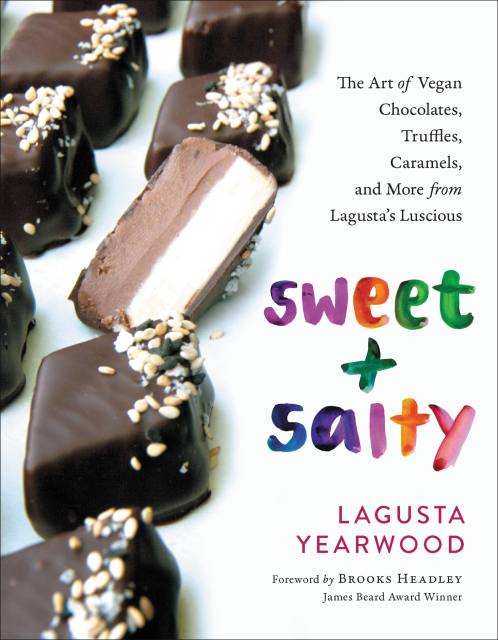

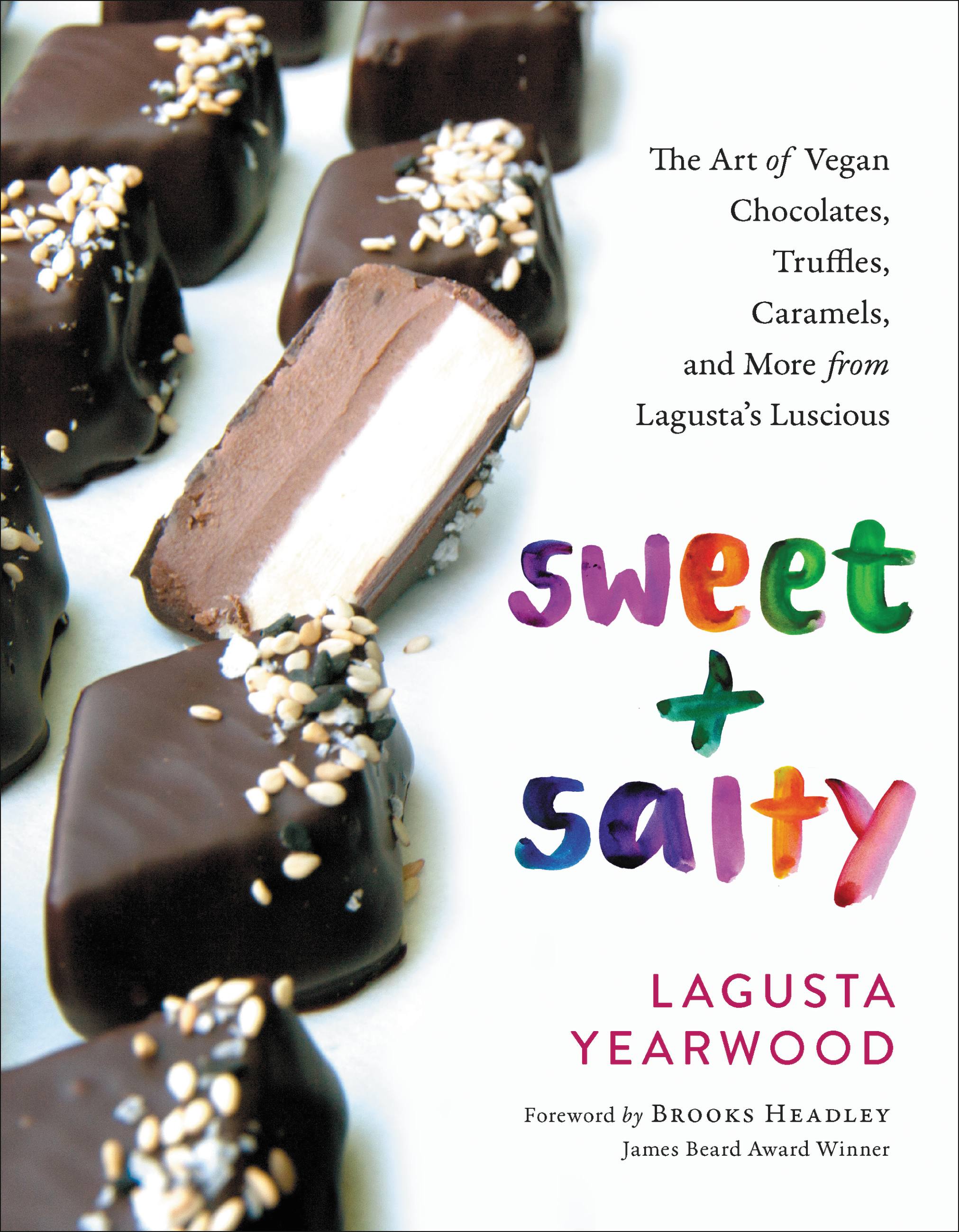

Sweet + Salty

The Art of Vegan Chocolates, Truffles, Caramels, and More from Lagusta's Luscious

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 24, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

At her East Coast confectionery shops, Lagusta Yearwood takes vegan sweets to the next level, going beyond cookies, cupcakes, and pies. Sweet + Salty features over 100 luscious recipes for caramels, chocolates, bonbons, truffles, and more for anyone looking to make their own vegan confections at home. With everything from the most basic caramel to bold, arresting flavors incorporating unexpected spices and flavors such as miso caramel sauce, thyme-preserved lemon sea-salt caramels, matzo toffee, and more, Sweet + Salty is a smart, sassy, completely innovative introduction to vegan confections.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 24, 2019

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Lifelong Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780738235066

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use