Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

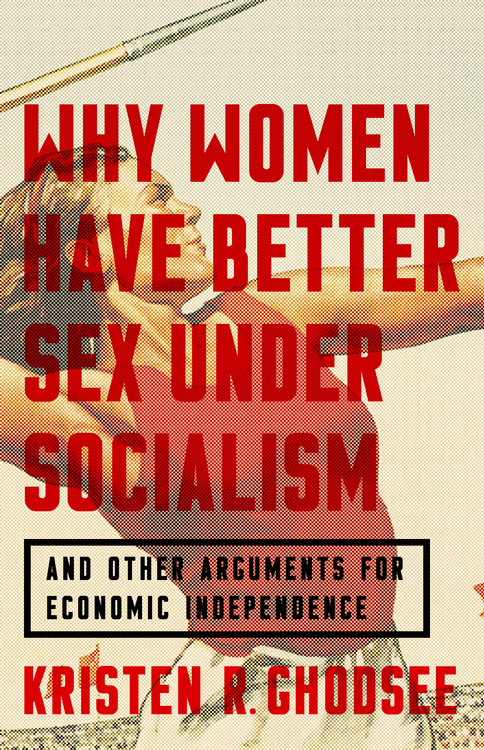

Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism

And Other Arguments for Economic Independence

Contributors

Read by Esther Wane

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.99Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 20, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In a witty, irreverent op-ed piece that went viral, Kristen Ghodsee argued that women had better sex under socialism. The response was tremendous — clearly she articulated something many women had sensed for years: the problem is with capitalism, not with us.

Ghodsee, an acclaimed ethnographer and professor of Russian and East European Studies, spent years researching what happened to women in countries that transitioned from state socialism to capitalism. She argues here that unregulated capitalism disproportionately harms women, and that we should learn from the past. By rejecting the bad and salvaging the good, we can adapt some socialist ideas to the 21st century and improve our lives.

She tackles all aspects of a woman's life – work, parenting, sex and relationships, citizenship, and leadership. In a chapter called "Women: Like Men, But Cheaper," she talks about women in the workplace, discussing everything from the wage gap to harassment and discrimination. In "What To Expect When You're Expecting Exploitation," she addresses motherhood and how "having it all" is impossible under capitalism.

Women are standing up for themselves like never before, from the increase in the number of women running for office to the women's march to the long-overdue public outcry against sexual harassment. Interest in socialism is also on the rise — whether it's the popularity of Bernie Sanders or the skyrocketing membership numbers of the Democratic Socialists of America. It's become increasingly clear to women that capitalism isn't working for us, and Ghodsee is the informed, lively guide who can show us the way forward.

Genre:

-

"Wonderful ... Kristen Ghodsee doesn't wear rose-tinted spectacles ... but she seeks with great brio and nuance to lay out what some socialist states achieved for women ... That Ghodsee also makes this a joyous read is the cherry on the cake."Suzanne Moore, Observer

-

"Brilliant ... engaging ... Ghodsee is not naive [and] brings the necessary scepticism to her thesis [which] comes into sharp focus when she looks at what happened after the Wall fell ... [a] valuable record of how things were and how they could be."Rosie Boycott, Financial Times

-

"Convincing, provocative and useful."Times Higher Education

-

"The virtue of Ghodsee's smart, accessible book is that it illustrates how it might be possible for a woman-or, for that matter, a man-to have an entirely different structural relationship to something as fundamental as sex, or health...Rebecca Mead, TheNew Yorker

Ghodsee approvingly notes the growing appeal of socialist ideas among young people in the United States and Western Europe, and her book is a useful reminder that the spread of these ideas would not just advantage the Bernie bros but might also better women's lives in significant ways. More orgasms alone might be a fine thing. But a change in the structural conditions under which more orgasms might be possible is another level of turn-on entirely." -

"With acumen and wit, [Ghodsee] lays bare the inequities women face under capitalism and the desirability of decoupling 'love and intimacy from economic considerations.'"O Magazine

-

"What if all it takes to get laid more is to embrace democratic socialism?... Ghodsee demonstrates how, historically, women have reported greater sexual satisfaction under democratic socialist (and even communist) governments."Sophia Benoit, GQ Magazine

-

"[A] short, crisp and wonderfully engaging polemic [that] couldn't be more urgent.... A tonic for a badly ailing discourse.... Ghodsee's book shows that for women, socialism can at least improve the conditions for pleasure, and perhaps inextricably, love."Liza Featherstone, Jacobin

-

"A provocative and deftly argued text."Broadly

-

"Capitalism has fundamentally shaped and warped the ways we relate to each other, sexually and otherwise...leading us to view intimacy and love as things that only exist in finite quantities, and that are only worth investing in worthy relationships. Ghodsee's book offers an alternative to this model, looking back at the state-socialist regimes in the 20th century, under which the state liberalized divorce laws, legalized abortion, invested in collective laundries and nurseries, and enabled women to attain more economic freedom-and in turn, better sex."The Cut

-

"A straightforward account of how capitalism harms women-including, yes, in our intimate lives... It made me want to do much more than vote."Jewish Currents

-

"Ghodsee's focus...on sex and sexual relations emerges elegantly from the argument she has developed: that a feminist politics is central to socialism because it cannot avoid its foundation in economic principles. So long as women are economically dependent on men, there can be no equality; without such equality, she argues, heterosexual relations will suffer and so will the experience of sex itself."In These Times

-

"There are many reasons to revisit socialist policies in a time of widening inequality, but a feminist perspective offers some of the most powerful incentives."The Guardian

-

"Reliant on the commodification of everything, capitalism's triumph is a calamity for most women. Their hard slog as mothers and careers can never be remunerated within market societies which, by design, are compelled to commodify their sexuality, robbing them in the process of their autonomy, even of the opportunity to enjoy sex for-themselves. Without romanticizing formerly communist regimes, Ghodsee's new book retrieves brilliantly the plight of hundreds of millions of women in those countries as they were being stripped of state support and thrust into brutal, unfettered markets. Employing personal anecdotes, forays into the history of the women's movement and an incisive mind, Ghodsee is enabling us to overcome the unnecessary tension between identity and class politics on the road towards the inclusive, progressive movement for societal change we so desperately need."Yanis Varoufakis, author of Adults in the Room

-

"A quietly damning indictment of the Lean In approach to women's empowerment through the corporate boardroom. Ghodsee makes a compelling case for a more expansive understanding of feminism, where remaking the economy is central. A necessary reminder that today's socialism should be as much about pleasure as it is about power and production."Kate Aronoff, coeditor of Democratic Socialism, American Style

-

"This book is funny, angry, and urgent-it's going to make readers think very differently about how they work, and how they live. Ghodsee is going to start a revolution. I'm already making a placard."Daisy Buchanan, author of How To Be a Grown-Up

-

"A passionate but reasoned feminist socialist manifesto for the 21st century... Ghodsee's treatise will be of interest to women becoming disillusioned with the capitalism under which they were raised."Publishers Weekly

-

"A pointed examination of the Soviet experiment... Using her years living in Bulgaria as fodder for the narrative, along with decades of research, [Ghodsee] makes the case that there are lessons capitalist countries can and should learn from socialism... At the same time, the author isn't blind to the failures of socialist regimes... While the title is the literary version of click-bait, the book is chock-full of hard-hitting real talk."Kirkus Reviews

- On Sale

- Nov 20, 2018

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549171178

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use