By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

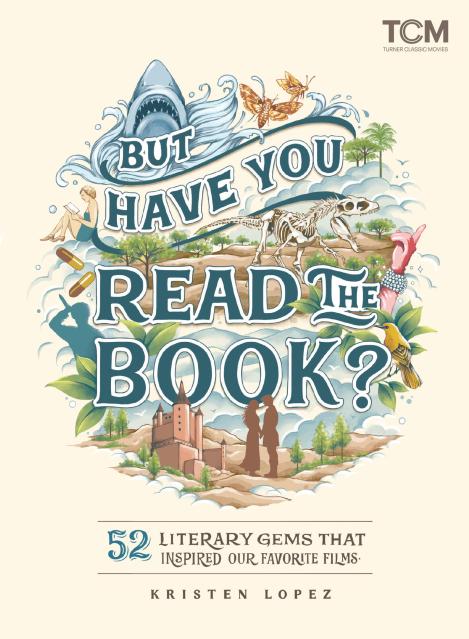

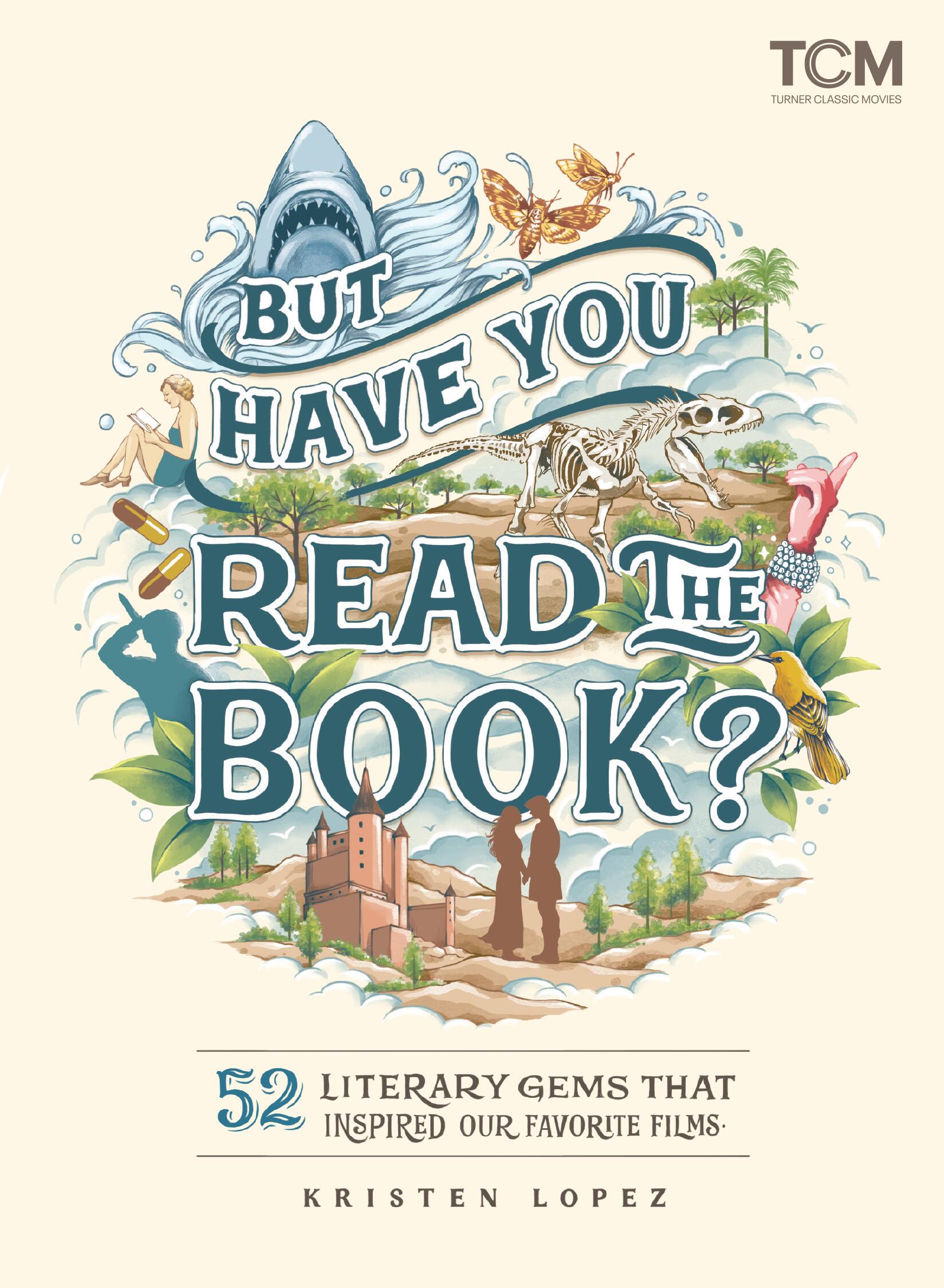

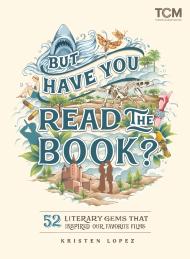

But Have You Read the Book?

52 Literary Gems That Inspired Our Favorite Films

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 7, 2023

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762480982

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $20.00 $26.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 7, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“I love that movie!”

“But have you read the book?”

Within these pages, Turner Classic Movies offers an endlessly fascinating look at 52 beloved screen adaptations and the great reads that inspired them. Some films, like Clueless—Amy Heckerling’s interpretation of Jane Austen’s Emma—diverge wildly from the original source material, while others, like One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, shift the point of view to craft a different experience within the same story. Author Kristen Lopez explores just what makes these works classics of both the page and screen, and why each made for an exceptional adaptation—whether faithful to the book or exemplifying cinematic creative license.

Other featured works include:

Children of Men · The Color Purple · Crazy Rich Asians · Dr. No · Dune · Gentlemen Prefer Blondes · Kiss Me Deadly · The Last Picture Show · Little Women · Passing · The Princess Bride · The Shining · The Thin Man · True Grit · Valley of the Dolls · The Virgin Suicides · Wuthering Heights

Series:

-

“If you’re a big reader who also loves movies, you’ll get a kick out of [this] cleverly designed anthology . . . Irresistible.”Ron Charles, The Washington Post

-

"An impressively entertaining and erudite collection of essays . . . 'But Have You Read The Book?' does its job well: it's the kind of read that'll leave you running to both your reading list and your watchlist to add several titles to the top."Valerie Ettenhofer, Slash Film

-

"An engaging tour of various routes from page to film, be they departures, copies or—not implausibly—both simultaneously . . . Spanning Frankenstein to Fight Club, The Lord of the Rings to Little Women, Lopez shows how the art of adaptation is about negotiation, not simply rejection or reverence. And, if nothing else, she gives you a fine reading list to follow."Total Film

-

“Lopez compiles the best film adaptations in a sweet, compact volume . . . Lopez's writing is lively . . . A good resource for book clubs and movie buffs alike.”Booklist

-

“A compendium of 52 stories taken from print to screen [that] parses differences between the versions of each story, pointing out actor credits and box office facts for the movies and themes explored in the books. So is But Have You Read the Book? for film buffs or book nerds? I say both.”Susannah Felts, BookPage

-

"A fun and handy guide for book lovers who wonder if they should watch the film adaptation, and for movie lovers who wonder if they should read the source material for a favorite flick."Shelf Awareness

-

"With [this] lovely book readers and cinephiles will now have a wonderful guide to assist with finding their next favorite read or watch."MovieJawn

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use