Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

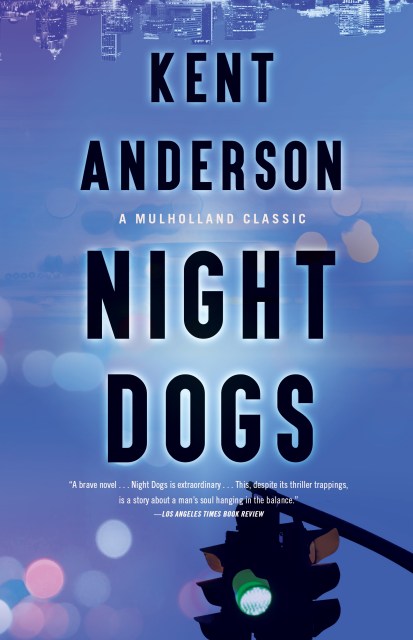

Night Dogs

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Prices

- Sale Price $2.99

- Regular Price $9.99

- Discount (70% off)

Prices

- Sale Price $2.99 CAD

- Regular Price $12.99 CAD

- Discount (77% off)

Format

Format:

- ebook $2.99 $2.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 13, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

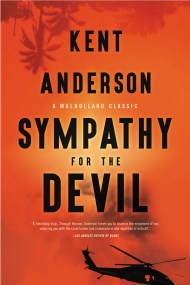

Two kinds of cops find their way to Portland’s North Precinct: those who are sent there for punishment, and those who come for the action. Officer Hanson is the second kind, a veteran who survived the war in Vietnam only to decide he wanted to keep fighting at home. Hanson knows war, and in this battle for the Portland streets, he fights not for the law but for his own code of justice.

Yet Hanson can’t outrun his memories of another, warmer battleground. A past he thought he’d left behind, that now threatens to overshadow his future. An enemy, this time close to home, is prying into his war record. Pulling down the shields that protect the darkest moments of that fevered time. Until another piece of his past surfaces, and Hanson risks his career, his sanity–even his life–for honor.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Nov 13, 2018

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Mulholland Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316489515

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use