By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

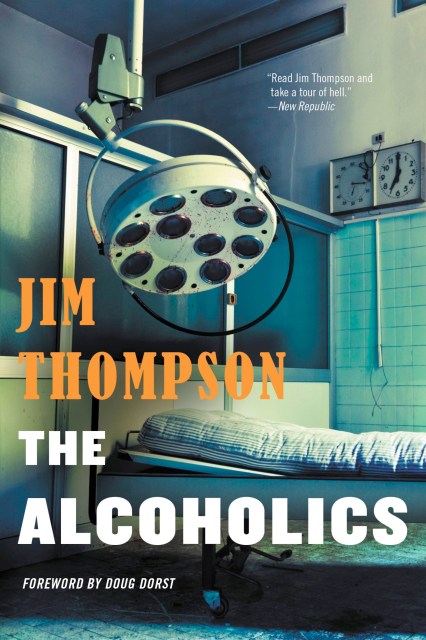

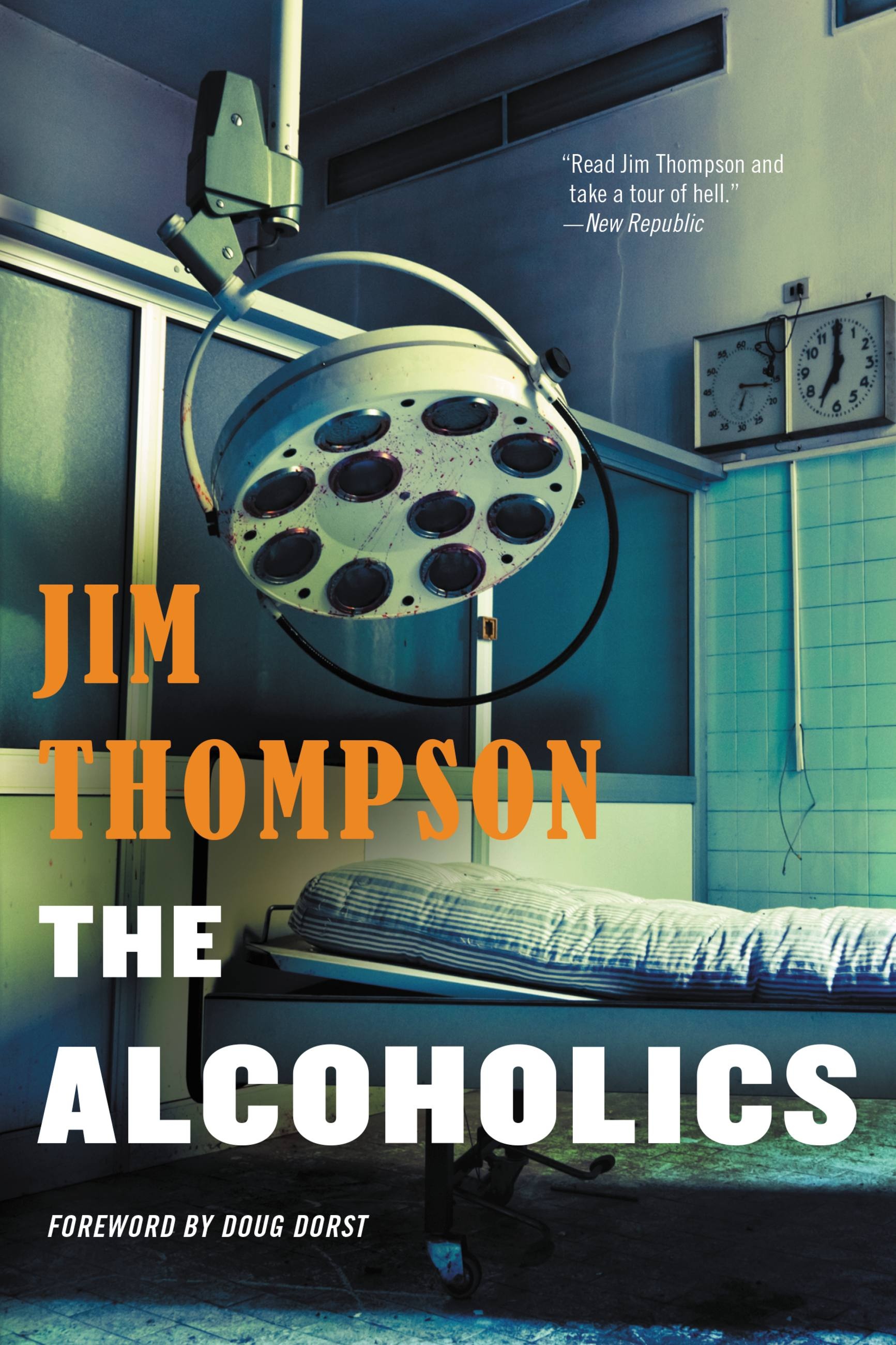

The Alcoholics

Contributors

By Jim Thompson

Foreword by Doug Dorst

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 5, 2014

- Page Count

- 192 pages

- Publisher

- Mulholland Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316403955

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 5, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Dr. Peter S. Murphy needs fifteen thousand dollars by the end of the day, or the city of Los Angeles can say goodbye to the El Healtho clinic. A recovery center for the most severe cases of alcoholism in the state — even if no one ever does quite seem to get dry there — El Healtho has been the bane of Dr. Murphy’s existence ever since he started running it. But now that its doors are about to close forever, Dr. Murphy finds he’ll do anything to keep it open.

Up to and including admitting Humphrey Van Twyne III, a patient with an extremely violent past whose wealthy family has the means to keep El Healtho open for business. Sure, the man isn’t exactly an alcoholic. And yes, what he really needs is to be under the care of the surgeons who performed the lobotomy that’s rendered Van Twyne all but a vegetable. But the money’s good — until the rag-tag group of ne’er-do-wells at El Healtho begin to wreak havoc with Dr. Murphy’s plans, and suddenly no one day has ever seemed so long.

A literary precursor to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, The Alcoholics is Thompson like you’ve never read him before, a pitch-black, mad-cap portrait of deviant behavior that is at once darkly comic, humane and harrowing.

Up to and including admitting Humphrey Van Twyne III, a patient with an extremely violent past whose wealthy family has the means to keep El Healtho open for business. Sure, the man isn’t exactly an alcoholic. And yes, what he really needs is to be under the care of the surgeons who performed the lobotomy that’s rendered Van Twyne all but a vegetable. But the money’s good — until the rag-tag group of ne’er-do-wells at El Healtho begin to wreak havoc with Dr. Murphy’s plans, and suddenly no one day has ever seemed so long.

A literary precursor to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, The Alcoholics is Thompson like you’ve never read him before, a pitch-black, mad-cap portrait of deviant behavior that is at once darkly comic, humane and harrowing.

Series:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use