Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

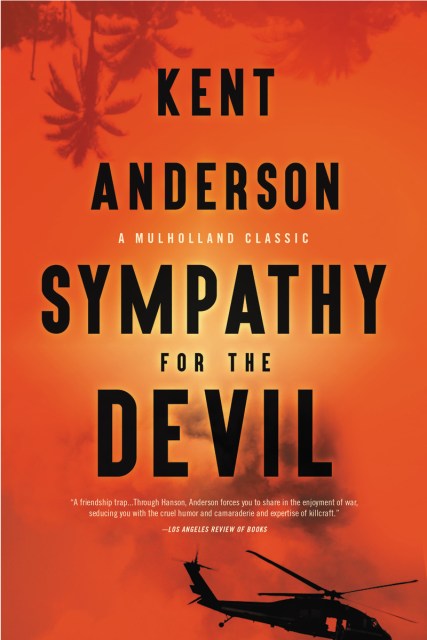

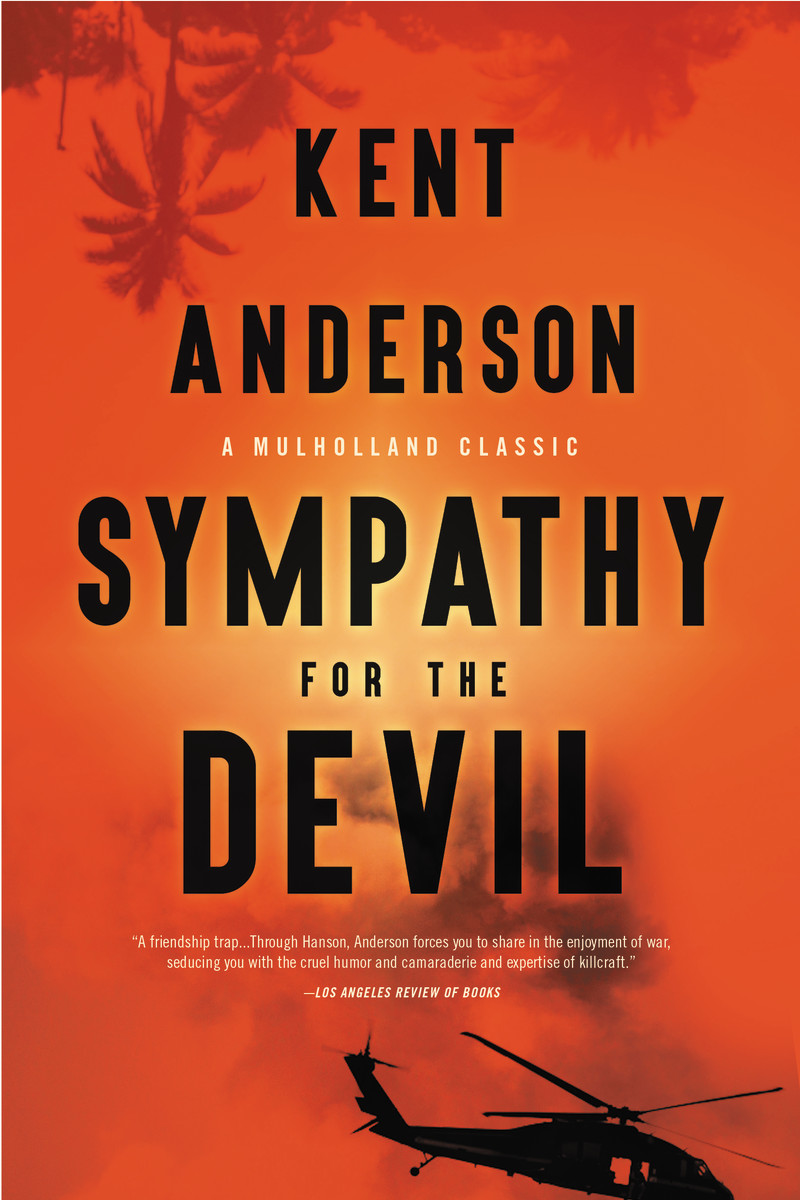

Sympathy for the Devil

Contributors

Foreword by David Morrell

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 30, 2019

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Mulholland Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316489485

Price

$16.99Price

$22.49 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.49 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 30, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Kent Anderson’s stunning debut novel is a modern classic, a harrowing, authentic picture of one American soldier’s experience of the Vietnam War–“unlike anything else in war literature” (Los Angeles Review of Books).

Hanson joins the Green Berets fresh out of college. Carrying a volume of Yeats’s poems in his uniform pocket, he has no idea of what he’s about to face in Vietnam–from the enemy, from his fellow soldiers, or within himself. In vivid, nightmarish, and finely etched prose, Kent Anderson takes us through Hanson’s two tours of duty and a bitter, ill-fated return to civilian life in-between, capturing the day-to-day process of war like no writer before or since.

Genre:

-

"Fiction that wounds and stings.... Sympathy for the Devil is a wonderful achievement , written fluently andperceptively, and with the kind of unsparing intelligence that is rooted in careful observation.... Kent Anderson has outwritten just about everybody who preceded him in trying to make fictional sense out of the war."Peter Straub, Washington Post

-

"An ending unlike anything else in war literature ... a nihilist ordeal of such power that comedy and tragedy flow into one another, and you can only watch numbly as your values float away facedown in the river."Los Angeles Review of Books