By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

Nothing More than Murder

Contributors

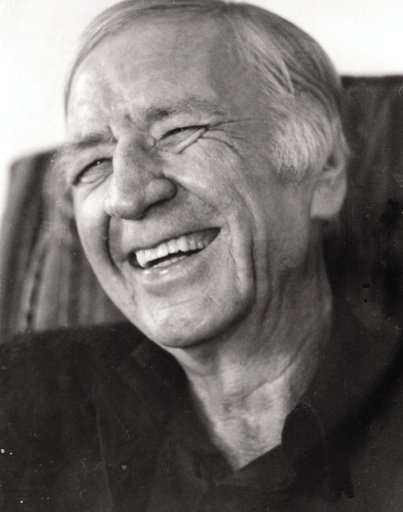

By Jim Thompson

Foreword by Joe R. Lansdale

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 5, 2014

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Mulholland Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316403931

Price

$15.00Price

$17.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $15.00 $17.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 5, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Joe Wilmot can’t stand his wife Elizabeth. But he sure loves her movie theater. It’s a modest establishment in a beat-down town–but Joe has the run of the place, and inside its walls, he’s king. Without the theater, he’d be sunk. Without his leadership, the theater would close in a heartbeat. If it isn’t the life Joe imagined for himself, at the very least, it’s livable.

Everything changes when Joe falls for the housemaid Carol, and the two can’t keep it a secret from Elizabeth. Elizabeth won’t leave Joe the theater unless he provides for her…but he’s put all his money into the show house.

Carol and Joe’s only hope is the life insurance policies they’ve taken out on each other. If one of them were to be presumed dead, they’d have more than enough money to solve all their problems…

No one knows murder better than Jim Thompson and in this incisive foray into the dark dealings of the mid-20th century movie industry, he doesn’t disappoint, in the riveting story of a love triangle gone horribly wrong, and just how far one man will go to hold on to a desperate dream.

Everything changes when Joe falls for the housemaid Carol, and the two can’t keep it a secret from Elizabeth. Elizabeth won’t leave Joe the theater unless he provides for her…but he’s put all his money into the show house.

Carol and Joe’s only hope is the life insurance policies they’ve taken out on each other. If one of them were to be presumed dead, they’d have more than enough money to solve all their problems…

No one knows murder better than Jim Thompson and in this incisive foray into the dark dealings of the mid-20th century movie industry, he doesn’t disappoint, in the riveting story of a love triangle gone horribly wrong, and just how far one man will go to hold on to a desperate dream.

Series:

-

"The best suspense writer going, bar none."The New York Times

-

"My favorite crime novelist-often imitated but never duplicated."Stephen King

-

"If Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett and Cornell Woolrich would have joined together in some ungodly union and produced a literary offspring, Jim Thompson would be it...His work...casts a dazzling light on the human condition."Washington Post

-

"Like Clint Eastwood's pictures it's the stuff for rednecks, truckers, failures, psychopaths and professors ... one of the finest American writers and the most frightening, [Thompson] is on best terms with the devil. Read Jim Thompson and take a tour of hell."The New Republic

-

"The master of the American groin-kick novel."Vanity Fair

-

"The most hard-boiled of all the American writers of crime fiction."Chicago Tribune

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use