By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

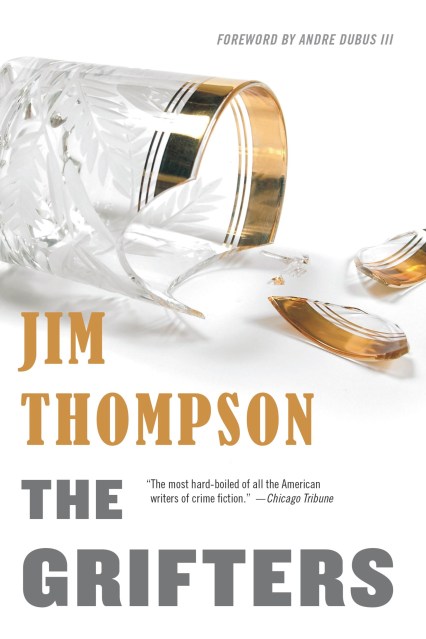

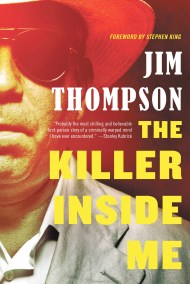

The Grifters

Contributors

Foreword by Andre Dubus III

By Jim Thompson

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 5, 2014

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Mulholland Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316404051

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 5, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

To his friends, to his coworkers, and even to his mistress Moira, Roy Dillon is an honest hardworking salesman. He lives in a cheap hotel just within his pay bracket. He goes to work every day. He has hundreds of friends and associates who could attest to his good character.

Yet, hidden behind three gaudy clown paintings in Roy’s pallid hotel room, sits fifty-two thousand dollars — the money Roy makes from his short cons, his “grifting.” For years, Roy has effortlessly maintained control over his house-of-cards life — until the simplest con goes wrong, and he finds himself critically injured and at the mercy of the most dangerous woman he ever met: his own mother.

Series:

-

"The best suspense writer going, bar none."The New York Times

-

"My favorite crime novelist-often imitated but never duplicated."Stephen King

-

"If Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett and Cornell Woolrich would have joined together in some ungodly union and produced a literary offspring, Jim Thompson would be it...His work...casts a dazzling light on the human condition."Washington Post

-

"Like Clint Eastwood's pictures it's the stuff for rednecks, truckers, failures, psychopaths and professors ... one of the finest American writers and the most frightening, [Thompson] is on best terms with the devil. Read Jim Thompson and take a tour of hell."The New Republic

-

"The master of the American groin-kick novel."Vanity Fair

-

"The most hard-boiled of all the American writers of crime fiction."Chicago Tribune

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use