Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

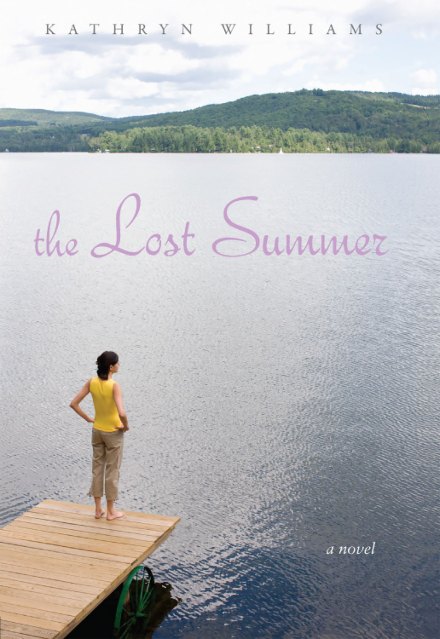

The Lost Summer

Contributors

By Kathryn Williams

Formats and Prices

Price

$7.99Price

$9.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $7.99 $9.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 26, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“I died one summer, or I almost did. Part of me did. I don’t say that to be dramatic, only because it’s true.”

For the past nine years, Helena Waite has been returning to summer camp at Southpoint. Every year the camp and its familiar routines, landmarks, and people have welcomed her back like a long-lost family member. But this year she is returning not as a camper, but as a counselor, while her best friend, Katie Bell remains behind. All too quickly, Helena discovers that the innocent world of campfires, singalongs, and field days have been pushed aside for late night pranks on the boys’ camp, skinny dipping in the lake, and stolen kisses in the hayloft. As she struggles to define herself in this new world, Helena begins to lose sight of what made camp special and the friendships that have sustained her for so many years. And when Ransome, her longtime crush, becomes a romantic reality, life gets even more confusing.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 26, 2010

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781423141563

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use