By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

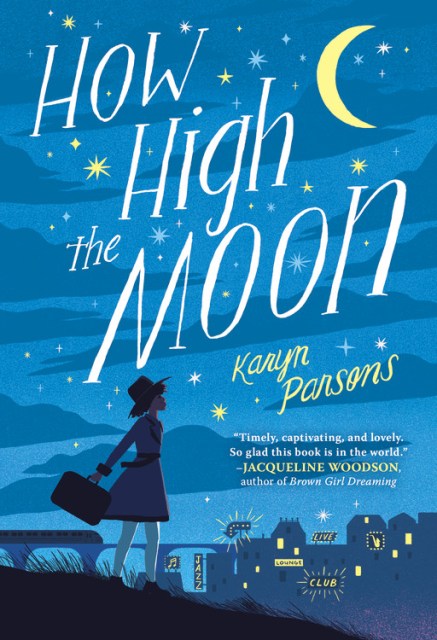

How High the Moon

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$22.49 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $16.99 $22.49 CAD

- ebook $6.99 $8.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $8.99 $11.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 5, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“Timely, captivating, and lovely. So glad this book is in the world.” —Jacqueline Woodson, author of Brown Girl Dreaming

In the small town of Alcolu, South Carolina, in 1944, 12-year-old Ella spends her days fishing and running around with her best friend Henry and cousin Myrna. But life is not always so sunny for Ella, who gets bullied for her light skin tone and whose mother is away pursuing her dream as a jazz singer.

So Ella is ecstatic when her mother invites her to visit for Christmas. Little does she expect the truths she will discover about her mother, the father she never knew, and her family’s most unlikely history.

After a life-changing month, Ella returns South and is shocked by the news that her schoolmate George has been arrested for the murder of two local white girls.

Poignant and eye-opening, How High the Moon is a timeless novel about a girl finding herself in a world all but determined to hold her down.

So Ella is ecstatic when her mother invites her to visit for Christmas. Little does she expect the truths she will discover about her mother, the father she never knew, and her family’s most unlikely history.

After a life-changing month, Ella returns South and is shocked by the news that her schoolmate George has been arrested for the murder of two local white girls.

Poignant and eye-opening, How High the Moon is a timeless novel about a girl finding herself in a world all but determined to hold her down.

-

"How High the Moon is at once historical and timely, captivating, and lovely. In Karyn Parsons brilliant hands, I feel like I've traveled a lifetime into the heartbreaking and beautiful south of the 1940s, spent time with Ella, Myrna and Henry and the many other amazing people I've met in this book, then landed back here in the present day having left a part of me behind. So glad this book is in the world."Jacqueline Woodson, author of Brown Girl Dreaming

-

"In How High the Moon, Karyn Parson brings the same verve, timing, and emotive brilliance that she brought to the screen. Equal parts mystery, historical fiction, and coming-of-age, this is a story full of warmth and light and drama that will captivate you. That will haunt you. And that will ultimately enlighten you."Kwame Alexander, New York Times bestselling author of The Door of No Return

-

"A talented, engaging new voice. A brave, compassionate, and lovable heroine."Jewell Parker Rhodes, author of Ghost Boys

-

"Parson's sparkling debut grabs us by the heart and leads us by the hand into a painful past filled with revelations, hope, and homecoming. Absolutely glorious!"Rita Williams Garcia, author of One Crazy Summer

-

"A tender and compelling story about loving and belonging. Parsons masterfully takes us on a journey where the political is personal, where the most heartbreaking moments are also profound and beautiful. Ella is a character readers will care about, cry with, and cheer for. How High the Moon is a stunning debutthat promises to have readers wanting more and more from Parsons."Renee Watson, author of Piecing Me Together

-

"A timeless tale that uncovers family secrets and hidden histories for readers of all ages and backgrounds. Masterfully done!"Tami Charles, author of Like Vanessa

-

"A stirring, emotionally resonant debut, How High the Moon opens a fresh and sensitive window on a terrifying time, even as it introduces us to a lovable new heroine—Ella Louise!"Tony Abbott, author of Firegirl and The Great Jeff

-

* "As compelling as Brown Girl Dreaming, as character-driven as One Crazy Summer, and as historically illuminating as Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. A captivating novel that sheds new light on black childhood."Kirkus Reviews, starred review

-

* "Parsons has penned a vivid, compelling tale that will stay with readers long after they turn the final page."School Library Journal, starred review

-

"....wonderful voices and character interactions, and an evocative cover will draw readers."Booklist

-

"...a welcome addition to middle school readers."School Library Connection

-

"....historical fiction fans may nonetheless appreciate this look at racial tensions in both the South and the North in the World War II era."BCCB

- On Sale

- Mar 5, 2019

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316484008

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use