Promotion

Sign up for our newsletters to receive 20% off! Shop now. Exclusions apply.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

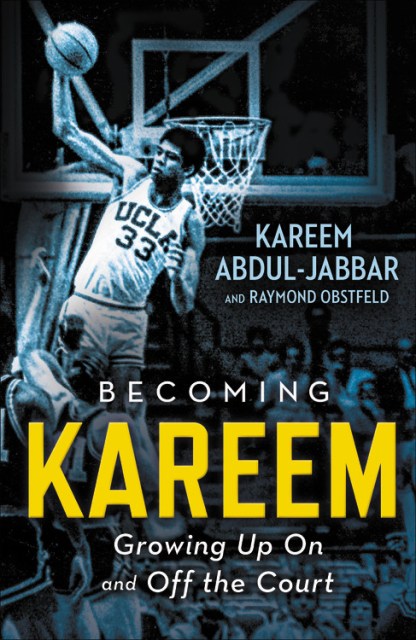

Becoming Kareem

Growing Up On and Off the Court

Contributors

By Raymond Obstfeld

Formats and Prices

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Hardcover $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Audiobook CD (Unabridged) $25.00 $32.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 6, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

At one time, Lew Alcindor was just another kid from New York City with all the usual problems: He struggled with fitting in, pleasing a strict father, and overcoming shyness that made him feel socially awkward. But with a talent for basketball, and an unmatched team of supporters, Lew Alcindor was able to transform and to become Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

From a childhood made difficult by racism and prejudice to a record-smashing career on the basketball court as an adult, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar's life was packed with ""coaches"" who taught him right from wrong and led him on the path to greatness. His parents, coaches Jack Donahue and John Wooden, Muhammad Ali, Bruce Lee, and many others played important roles in Abdul-Jabbar's life and sparked him to become an activist for social change and advancement. The inspiration from those around him, and his drive to find his own path in life, are highlighted in this personal and awe-inspiring journey.

Written especially for young readers, Becoming Kareem chronicles how Kareem Abdul-Jabbar become the icon and legend he is today, both on and off the court.

-

* "In our current moment when black athletes are joining the national confrontation with the nation's overwhelming legacy of racial injustice, few are better suited to provide context than Abdul-Jabbar.... Wrestling with what it means to be black, determining his own responsibility and capacity to respond to injustice, and becoming the "kindest, gentlest, smartest, lovingest version" of himself takes center stage in this retelling of the early part of his life. Like the author's unstoppable skyhook, this timely book is a clear score."Kirkus, starred review

-

* "More than a play-by-play sports story, it's an honest, powerful exposition of what it means to be black in white America, offering a de facto history of the civil rights movement."Booklist, starred review

-

* "This timely and unforgettable memoir is essential for middle and high school collections, and affords rich opportunities for classroom and book club discussions."SLJ, starred review

-

"Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is... as gifted an intellect as he is an athlete... It's a tale by a wise elder-- about basketball, sure, but also about cultural, political, social, and religious awakenings, big stuff narrated in a very accessible way."The New York Times Book Review

- On Sale

- Nov 6, 2018

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316555418

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use