Promotion

Sign up for our newsletters to receive 20% off! Shop now. Exclusions apply.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

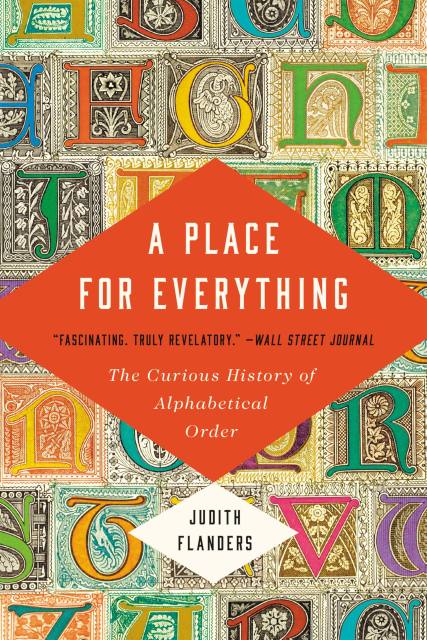

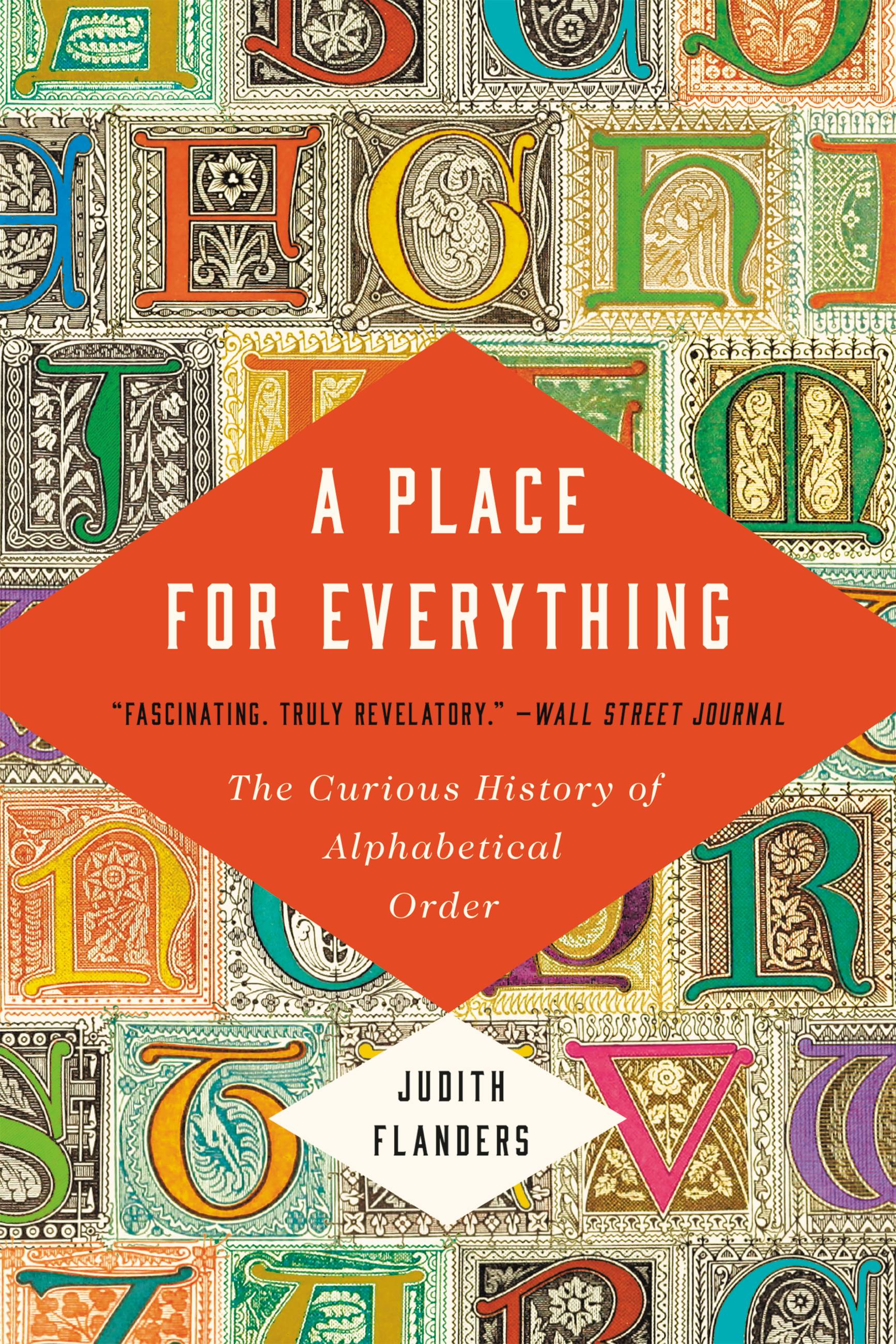

A Place for Everything

The Curious History of Alphabetical Order

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 3, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From a New York Times bestselling historian, the “truly revelatory” (Wall Street Journal) story of how the alphabet ordered our world

A Place for Everything is the first-ever history of alphabetization, from the Library of Alexandria to Wikipedia. Once we’ve learned our ABCs as children, few of us ever think of them again, but alphabetical order plays a material role in our adult lives. From school registers to electoral rolls, from dictionaries and encyclopedias to library shelves, the alphabet has ordered our lives, often invisibly. Yet the birth of alphabetization was a constant struggle: Medieval clergy felt that its use would upend the divine order of creation; elite institutions like Harvard and Yale long ranked students by the social status of their parents, rather than ordering them from A to Z. But eventually alphabetical order triumphed.

With wry humor, historian Judith Flanders offers a fascinating history of how the alphabet ordered our world.

-

"Fascinating... A Place for Everything rewards us with a fresh take on our quest to stockpile knowledge. It feels particularly relevant now that search engines are rendering old ways of organizing information obsolete...That we have acquired so much knowledge is astounding; that we have devised ways to find what we need to know quickly is what merits this original and impressive book."New York Times

-

"Fascinating . . . truly revelatory"Wall Street Journal

-

"One of the many fascinations of Judith Flanders's book is that it reveals what a weird, unlikely creation the alphabet is...an intriguing history not just of alphabetical order but of the human need for both pattern and intellectual efficiency."Guardian

-

"A charming repository of idiosyncrasy, a love letter to literacy that rightly delights in alphabetisation's exceptions as much as its rules."Financial Times

-

“This is an utterly charming book, packed with engrossing details.”The Times (UK)

-

"For readers who love language or armchair historians interested in the evolution of linguistics, this is catnip. For the mildly curious, it's accessible, narratively adventurous, and surprisingly insightful about how the alphabet marks us all in some way...A rich cultural and linguistic history."Kirkus

-

"A Place for Everything presents itself as a history of alphabetical order, but in fact it is much more than that. Rather, as the title suggests, it offers something like a general history of the various ways humans have sorted and filed the world around them."The Spectator

-

"A library and academic essential rather than a catchpenny popular read (that, by the way, is a compliment)."The Times of London

-

"Quirky and compelling... [Flanders] is a meticulous historian with a taste for the offbeat; the story of alphabetical order suits her well."Dan Jones, Sunday Times (UK)

-

"Surprising and copiously researched."Times Literary Supplement

-

"Flanders is one of our outstanding popular historians.... [A Place for Everything] is an exemplar of the form on which it focuses."The Critic

-

"Judith Flanders has a knack for making odd subjects accessible."i

-

“Flanders is especially good in discussing when and why alphabetical order was not used, or was resisted, even after it was available....The prose is engaging [and] the examples are to the point[.]”Jack Lynch, Dictionaries: Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America

- On Sale

- May 3, 2022

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541601161

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use