Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

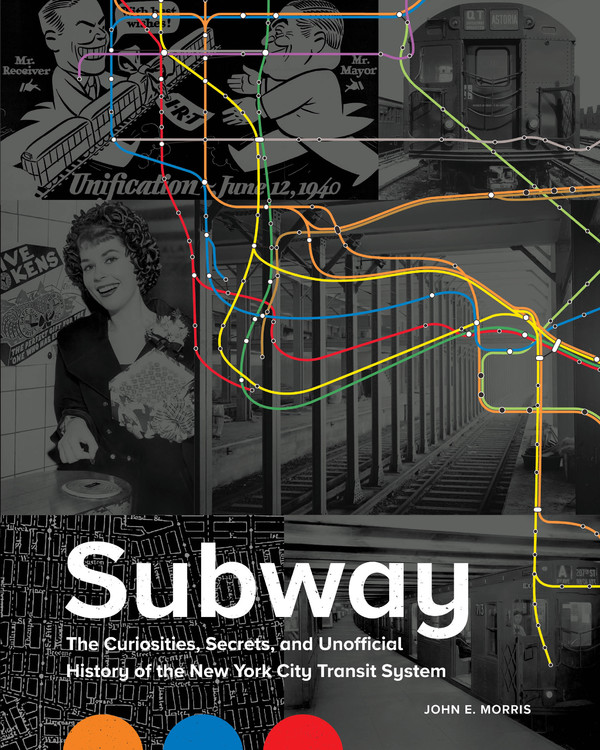

Subway

The Curiosities, Secrets, and Unofficial History of the New York City Transit System

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$30.00Price

$39.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $39.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 6, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This dynamic visual history of the world’s largest transit system — in all its intriguing, colorful, and even seedy glory — is packed with fascinating facts and hundreds of compelling photographs.

When the first New York subway line opened in 1904, it was the most advanced in the world and a source of enormous civic pride. Today, it is an essential function to the lives of New Yorkers and a perennial cultural touchstone. To be a New Yorker is to take the train. To celebrate it, or grumble about it.

Subway: The History, Curiosities, and Secrets of the New York City Transit System by John E. Morris is both a vivid history of this great transportation system and an exploration of its impact on the city and popular culture. The book covers every remarkable moment, from the technical obstacles and corruption that impeded plans for an underground rail line in the 1800s, to the current state of the system and plans for the future; profiles of the colorful, forgotten characters who built and restored the subway; graphics and imagery showing the evolution of subway cars and the way fares are collected; how subway etiquette rules have evolved with society; great subway chase scenes and songs about the subway; a look at abandoned stations and half-built tunnels; and more.

In this visually stunning work, packed with original research, journalist and bestselling author John Morris brings life to this one-time engineering marvel that has united and expanded the city for the last 116 years.

Genre:

-

"With a culture all its own, the subway truly is a city beneath the city. In Subway, John Morris takes readers on a breezy ride through that world that will inform and entertain everyday straphangers, transit aficionados, and even those who've never passed through the turnstiles."Jose Martinez, senior transit reporter at Thecity.nyc

-

"In a rollicking, fact-filled narrative and with hundreds of rarely seen images, John Morris tells the story of the birth of the New York City subway system, and how this underground world of tunnels and rails forever changed the shape and feel of the city."Esther Crain, founder of the website Ephemeral New York and author of The Gilded Age in New York, 1870-1910

-

"An encyclopedic history of the subway system. It's the historical record."Richard Ravitch, former chairman of the Metropolitan Transit Authority

-

"This beautiful tome to the subway would make a great coffee table book, but it’s also the perfect gift for any NYC history or transit buff, as it’s full of gorgeous vintage images and tons of fascinating facts."6Sqft.com

- On Sale

- Oct 6, 2020

- Page Count

- 264 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780762467907

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use