Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

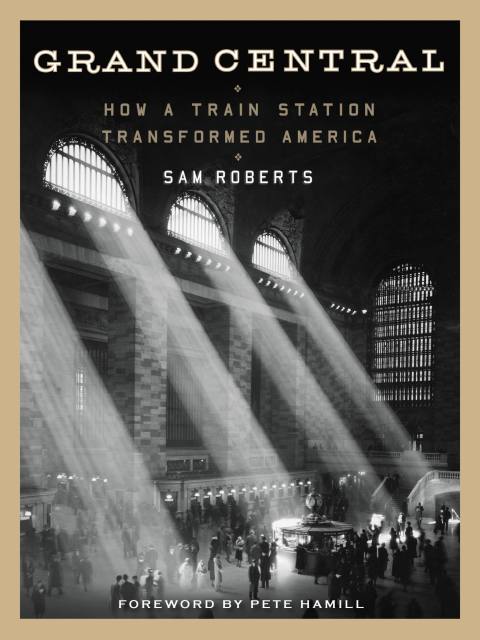

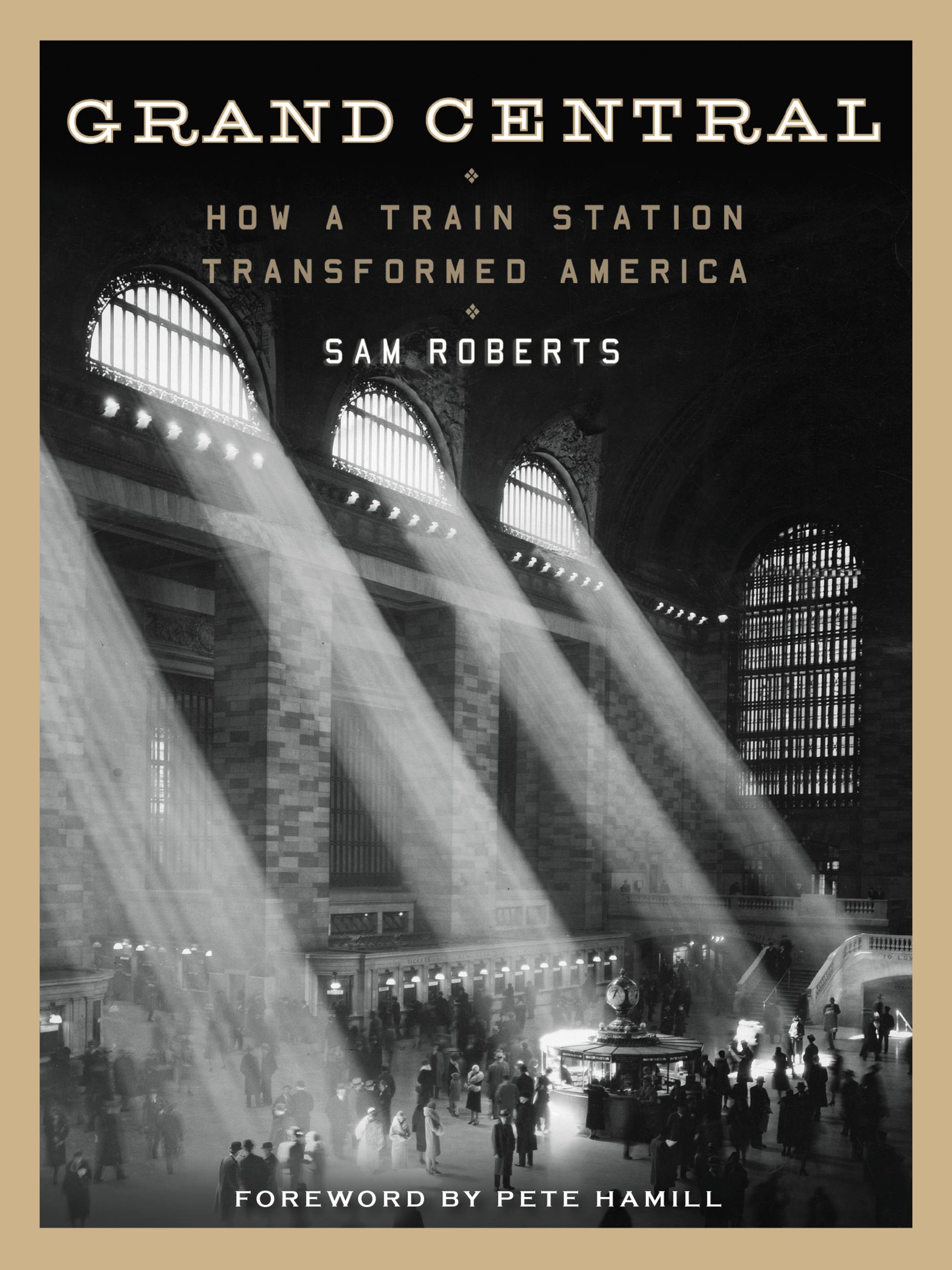

Grand Central

How a Train Station Transformed America

Contributors

By Sam Roberts

Foreword by Pete Hamill

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 12, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A rich, illustrated – and entertaining — history of the iconic Grand Central Terminal, from one of New York City’s favorite writers, just in time to celebrate the train station’s 100th fabulous anniversary.

In the winter of 1913, Grand Central Station was officially opened and immediately became one of the most beautiful and recognizable Manhattan landmarks. In this celebration of the one hundred year old terminal, Sam Roberts of The New York Times looks back at Grand Central’s conception, amazing history, and the far-reaching cultural effects of the station that continues to amaze tourists and shuttle busy commuters.

Along the way, Roberts will explore how the Manhattan transit hub truly foreshadowed the evolution of suburban expansion in the country, and fostered the nation’s westward expansion and growth via the railroad.

Featuring quirky anecdotes and behind-the-scenes information, this book will allow readers to peek into the secret and unseen areas of Grand Central — from the tunnels, to the command center, to the hidden passageways.

With stories about everything from the famous movies that have used Grand Central as a location to the celestial ceiling in the main lobby (including its stunning mistake) to the homeless denizens who reside in the building’s catacombs, this is a fascinating and, exciting look at a true American institution.

In the winter of 1913, Grand Central Station was officially opened and immediately became one of the most beautiful and recognizable Manhattan landmarks. In this celebration of the one hundred year old terminal, Sam Roberts of The New York Times looks back at Grand Central’s conception, amazing history, and the far-reaching cultural effects of the station that continues to amaze tourists and shuttle busy commuters.

Along the way, Roberts will explore how the Manhattan transit hub truly foreshadowed the evolution of suburban expansion in the country, and fostered the nation’s westward expansion and growth via the railroad.

Featuring quirky anecdotes and behind-the-scenes information, this book will allow readers to peek into the secret and unseen areas of Grand Central — from the tunnels, to the command center, to the hidden passageways.

With stories about everything from the famous movies that have used Grand Central as a location to the celestial ceiling in the main lobby (including its stunning mistake) to the homeless denizens who reside in the building’s catacombs, this is a fascinating and, exciting look at a true American institution.

Genre:

-

"This well-done piece of urban history will appeal to both railroad enthusiasts and general readers."Booklist

-

"A wonderful volume for New York City buffs or railroad aficionados, Roberts closes with discussions of some of the terminal's quirks and mysteries like the ubiquitous decorative acorns, the secret staircase, and various secret underground locations."Publishers Weekly

-

"Sam Roberts' book integrates a historical perspective with contemporary storytelling. This compelling narrative invites the reader into an immersive world of Grand Central that is personal, historically rich, and peppered with engaging anecdotes."American Institute of Architects

- On Sale

- Sep 12, 2017

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455525973

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use