Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

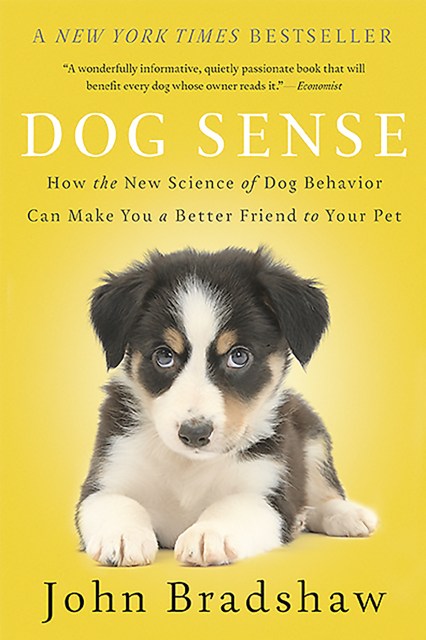

Dog Sense

How the New Science of Dog Behavior Can Make You A Better Friend to Your Pet

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 9, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

What dogs really need is a spokesperson, someone who will assert their specific needs. Renowned anthrozoologist Dr. John Bradshaw has made a career of studying human-animal interactions, and in Dog Sense he uses the latest scientific research to show how humans can live in harmony with — not just dominion over — their four-legged friends. From explaining why positive reinforcement is a more effective (and less damaging) way to control dogs’ behavior than punishment to demonstrating the importance of weighing a dog’s unique personality against stereotypes about its breed, Bradshaw offers extraordinary insight into the question of how we really ought to treat our dogs.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 9, 2014

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465053742

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use