Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

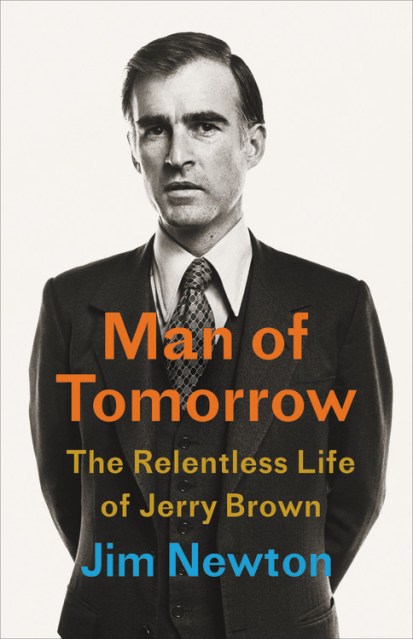

Man of Tomorrow

The Relentless Life of Jerry Brown

Contributors

By Jim Newton

Formats and Prices

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 12, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Visionary. Iconoclast. Political Survivor. “A powerful and entertaining look” (Governor Gavin Newsom) at the extraordinary life and political career of Governor Jerry Brown.

Jerry Brown is no ordinary politician. Like his state, he is eclectic, brilliant, unpredictable and sometimes weird. And, as with so much that California invents and exports, Brown’s life story reveals a great deal about this country.

With the exclusive cooperation of Governor Brown himself, Jim Newton has written the definitive account of Jerry Brown’s life. The son of Pat Brown, who served as governor of California through the 1960s, Jerry would extend and also radically alter the legacy of his father through his own service in the governor’s mansion. As governor, first in the 1970s and then again, 28 years later in his remarkable return to power, Jerry Brown would propound an alternative menu of American values: the restoration of the California economy while balancing the state budget, leadership in the international campaign to combat climate change and the aggressive defense of California’s immigrants, no matter by which route they arrived. It was a blend of compassion, far-sightedness and pragmatism that the nation would be wise to consider.

The story of Jerry Brown’s life is in many ways the story of California and how it became the largest economy in the United States. Man of Tomorrow traces the blueprint of Jerry Brown’s off beat risk-taking: equal parts fiscal conservatism and social progressivism. Jim Newton also reveals another side of Jerry Brown, the once-promising presidential candidate whose defeat on the national stage did nothing to diminish the scale of his political, intellectual and spiritual ambitions.

To the same degree that California represents the future of America, Jim Newton’s account of Jerry Brown’s life offers a new way of understanding how politics works today and how it could work in the future.

Genre:

-

A Los Angeles Times Bestseller One of LitHub's Most Anticipated Books of 2020A New & Noteworthy New York Times Selection

-

"Jerry Brown gets the biography he deserves...Man of Tomorrow, is a thoughtful look at the governor who shaped the state that has always reached the American future before the rest of the country. It is the play of this man of the mind against the experience of a veteran newsman that makes this volume a formidable contribution to the history of both the state and the country."David Shribman, Los Angeles Times

-

"A vivid and admiring biography of Brown"Mark Brilliant, Washington Post

-

"Newton brings his deep knowledge of California politics to an engaging, sympathetic biography of the state's 34th and 39th governor, Jerry Brown ...Newton follows all of Brown's ups and downs in a fluid, highly readable biography. A well-delineated portrait of an accomplished leader."Kirkus Reviews, starred

-

"Veteran journalist Jim Newton provides a thorough and sympathetic take on one of California's most significant and unconventional politicians."Anisse Gross, San Francisco Chronicle

-

"Newton brings serious cred to this project, having spent 25 years covering California government as a reporter, columnist, editorial-page editor, and editor at large for the Los Angeles Times. All of which is needed to trace the political life of one of the more thoughtful, influential, enigmatic, and resilient public servants in modern America. Newton avoids the quicksand of detail while still laying out the issues closest to Brown's heart and the political races he ran...Very nearly a must for the politics collection."Booklist

-

"An insider political biography that will have national appeal."Library Journal

-

"It's more than just a biography of the man; Newton believes Brown's career in California shows how politics works now and how it could work in the future, with Brown's signature blend of pragmatism and compassion."Napa Valley Register

-

"Jim Newton...explores in unparalleled detail the rich, varied and complex spiritual forces that have shaped the former governor and made him such a challenging political leader...There is much to be learned from his book."Fox and Hounds Daily

-

"Jim Newton tells Brown's story, finding in it the seeds of possibility for an America that is truly great."LitHub

-

"This is a powerful and entertaining look at California's one and only Jerry Brown. Newton gives the definitive account of Jerry's life and of the times and state that produced him. Man of Tomorrow is an important contribution to the history of California and the nation -- and an especially important one today."Governor Gavin Newsom

-

"A quirky, brilliant iconoclast, Jerry Brown led California twice-four decades apart. Newton's engrossing retelling of Brown's remarkable career and the history he lived and shaped is a must read for students of politics!"David Axelrod, author of Believer: My Forty Years in Politics

-

"In his splendid and fascinating book, Man of Tomorrow, Newton deftly traces the myriad reasons for Brown's stumbles and successes against the background of California's changing political demography. Brown gave the author exceptional access and Newton has responded with a revealing portrait of him and an important commentary on California. Whatever readers think of Brown, they will leave this book feeling that they know this hitherto enigmatic politician. That's quite an accomplishment."Lou Cannon, author ofGovernor Reagan and President Reagan

-

"Jerry Brown is one of the most intriguing and misunderstood figures in American history. To follow the man who was known as Governor Moonbeam and Linda Ronstadt's boyfriend-but who was also the savvy pol who saved the state of California-is a strange and fascinating trip. There is no better guide than Jim Newton, a vivid and insightful writer who knows his subject cold."Evan Thomas, authorof Robert Kennedy: His Life and First: Sandra Day O'Connor

-

"Jim Newton does an excellent job weaving California's modern history with the legacy of Jerry Brown, its longest-serving governor. His book captures the complexities of a man who is both a bold visionary and a practical leader, someone who transformed California into the model for fighting climate change while building the fifth-largest economy in the world."U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein

-

"In Man of Tomorrow: The Relentless Life of Jerry Brown, Jim Newton captures how the story of California parallels with the story of Jerry Brown. Whether it was the movements for worker rights, fair elections, the environment, or the importance of balanced budgets-Jerry gave Californians a steady hand of leadership through times that shaped California into the state we have today."U.S. Senator Kamala Harris, author of The Truths We Hold

- On Sale

- May 12, 2020

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316392464

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use