Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

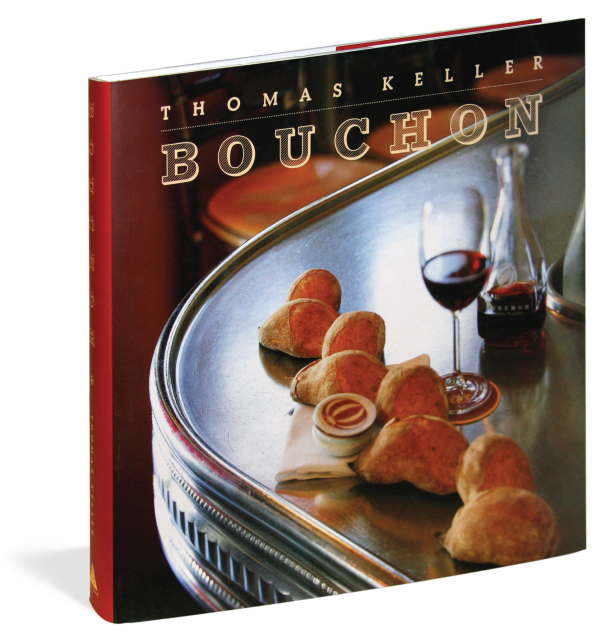

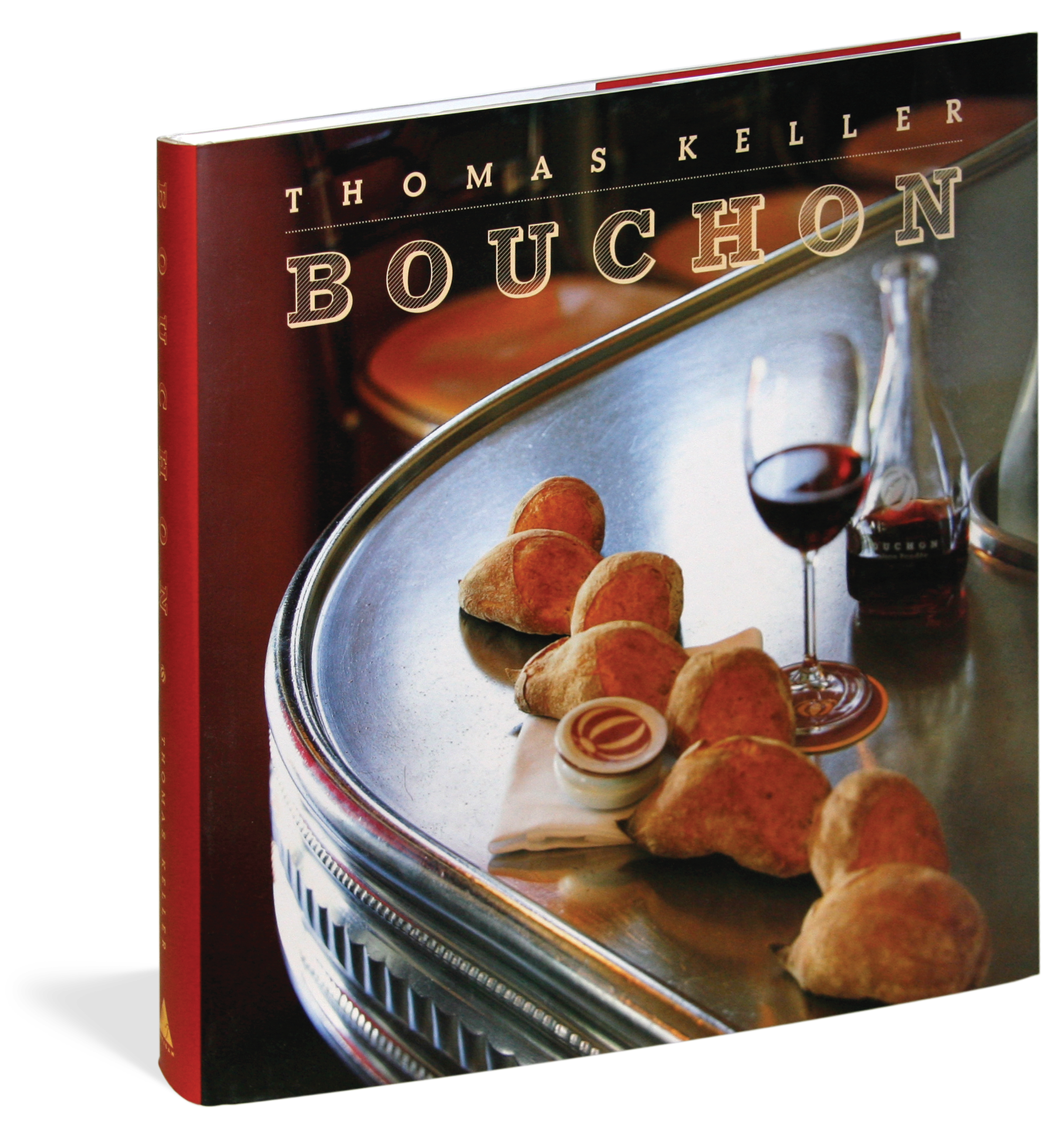

Bouchon

Contributors

With Jeffrey Cerciello

With Susie Heller

Photographs by Deborah Jones

With Michael Ruhlman

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 15, 2004

- Page Count

- 360 pages

- Publisher

- Artisan

- ISBN-13

- 9781579652395

Price

$60.00Price

$75.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $60.00 $75.00 CAD

- ebook $43.99 $56.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 15, 2004. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

James Beard Award Winner

IACP Award Winner

Thomas Keller, chef/proprieter of Napa Valley’s French Laundry, is passionate about bistro cooking. He believes fervently that the real art of cooking lies in elevating to excellence the simplest ingredients; that bistro cooking embodies at once a culinary ethos of generosity, economy, and simplicity; that the techniques at its foundation are profound, and the recipes at its heart have a powerful ability to nourish and please.

So enamored is he of this older, more casual type of cooking that he opened the restaurant Bouchon, right next door to the French Laundry, so he could satisfy a craving for a perfectly made quiche, or a gratinéed onion soup, or a simple but irresistible roasted chicken. Now Bouchon, the cookbook, embodies this cuisine in all its sublime simplicity.

But let’s begin at the real beginning. For Keller, great cooking is all about the virtue of process and attention to detail. Even in the humblest dish, the extra thought is evident, which is why this food tastes so amazing: The onions for the onion soup are caramelized for five hours; lamb cheeks are used for the navarin; basic but essential refinements every step of the way make for the cleanest flavors, the brightest vegetables, the perfect balance—whether of fat to acid for a vinaigrette, of egg to liquid for a custard, of salt to meat for a duck confit.

Because versatility as a cook is achieved through learning foundations, Keller and Bouchon executive chef Jeff Cerciello illuminate all the key points of technique along the way: how a two-inch ring makes for a perfect quiche; how to recognize the right hazelnut brown for a brown butter sauce; how far to caramelize sugar for different uses.

But learning and refinement aside—oh those recipes! Steamed mussels with saffron, bourride, trout grenobloise with its parsley, lemon, and croutons; steak frites, beef bourguignon, chicken in the pot—all exquisitely crafted. And those immortal desserts: the tarte Tatin, the chocolate mousse, the lemon tart, the profiteroles with chocolate sauce. In Bouchon, you get to experience them in impeccably realized form.

This is a book to cherish, with its alluring mix of recipes and the author’s knowledge, warmth, and wit: “I find this a hopeful time for the pig,” says Keller about our yearning for the flavor that has been bred out of pork. So let your imagination transport you back to the burnished warmth of an old-fashioned French bistro, pull up a stool to the zinc bar or slide into a banquette, and treat yourself to truly great preparations that have not just withstood the vagaries of fashion, but have improved with time. Welcome to Bouchon.

IACP Award Winner

Thomas Keller, chef/proprieter of Napa Valley’s French Laundry, is passionate about bistro cooking. He believes fervently that the real art of cooking lies in elevating to excellence the simplest ingredients; that bistro cooking embodies at once a culinary ethos of generosity, economy, and simplicity; that the techniques at its foundation are profound, and the recipes at its heart have a powerful ability to nourish and please.

So enamored is he of this older, more casual type of cooking that he opened the restaurant Bouchon, right next door to the French Laundry, so he could satisfy a craving for a perfectly made quiche, or a gratinéed onion soup, or a simple but irresistible roasted chicken. Now Bouchon, the cookbook, embodies this cuisine in all its sublime simplicity.

But let’s begin at the real beginning. For Keller, great cooking is all about the virtue of process and attention to detail. Even in the humblest dish, the extra thought is evident, which is why this food tastes so amazing: The onions for the onion soup are caramelized for five hours; lamb cheeks are used for the navarin; basic but essential refinements every step of the way make for the cleanest flavors, the brightest vegetables, the perfect balance—whether of fat to acid for a vinaigrette, of egg to liquid for a custard, of salt to meat for a duck confit.

Because versatility as a cook is achieved through learning foundations, Keller and Bouchon executive chef Jeff Cerciello illuminate all the key points of technique along the way: how a two-inch ring makes for a perfect quiche; how to recognize the right hazelnut brown for a brown butter sauce; how far to caramelize sugar for different uses.

But learning and refinement aside—oh those recipes! Steamed mussels with saffron, bourride, trout grenobloise with its parsley, lemon, and croutons; steak frites, beef bourguignon, chicken in the pot—all exquisitely crafted. And those immortal desserts: the tarte Tatin, the chocolate mousse, the lemon tart, the profiteroles with chocolate sauce. In Bouchon, you get to experience them in impeccably realized form.

This is a book to cherish, with its alluring mix of recipes and the author’s knowledge, warmth, and wit: “I find this a hopeful time for the pig,” says Keller about our yearning for the flavor that has been bred out of pork. So let your imagination transport you back to the burnished warmth of an old-fashioned French bistro, pull up a stool to the zinc bar or slide into a banquette, and treat yourself to truly great preparations that have not just withstood the vagaries of fashion, but have improved with time. Welcome to Bouchon.

Series:

-

"It may be the best cookbook ever about bistros and bistro food."

—The New York Times