By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

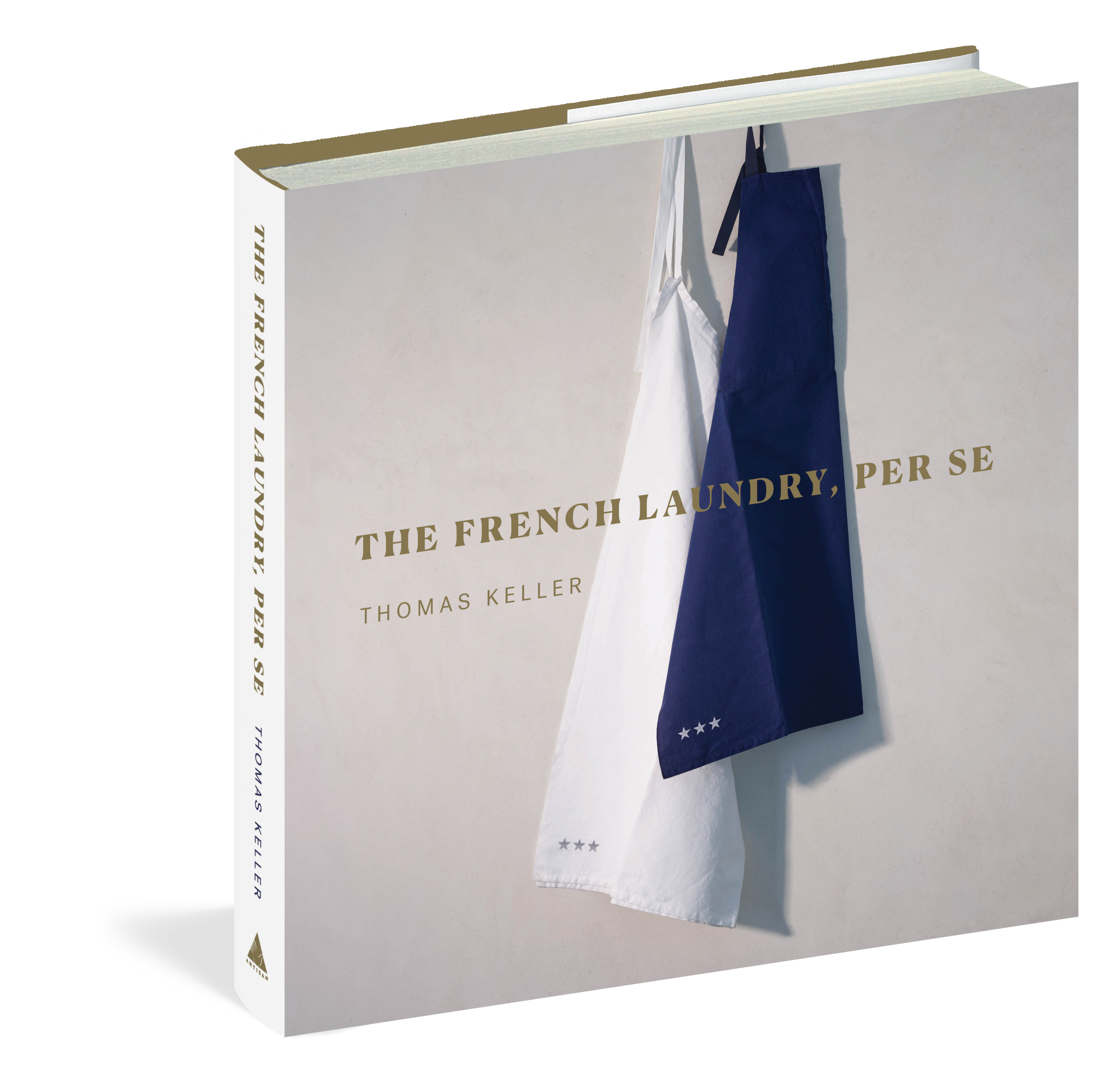

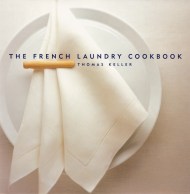

The French Laundry, Per Se

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 27, 2020

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Artisan

- ISBN-13

- 9781579658496

Price

$75.00Price

$95.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $75.00 $95.00 CAD

- ebook $54.99 $71.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 27, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Named a Best Cookbook of 2020 by Amazon and Barnes & Noble

“Every elegant page projects Keller’s high standard of ‘perfect culinary execution’. . . . This superb work is as much philosophical treatise as gorgeous cookbook.”

—Publishers Weekly, STARRED REVIEW

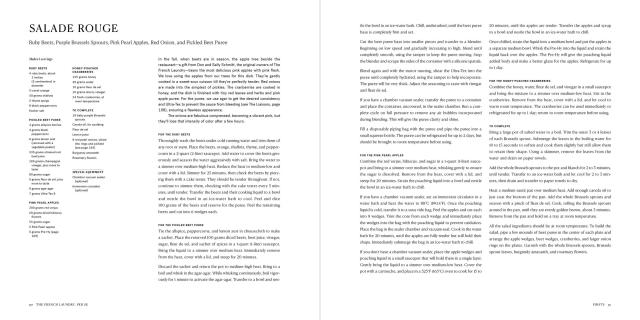

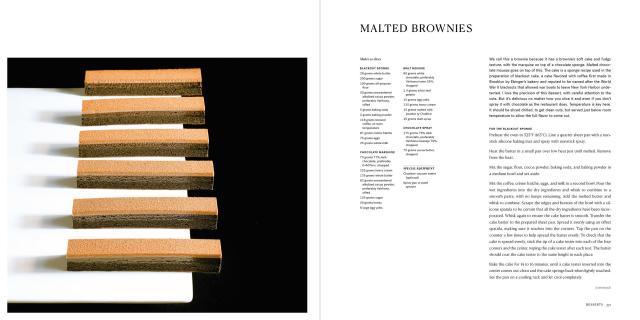

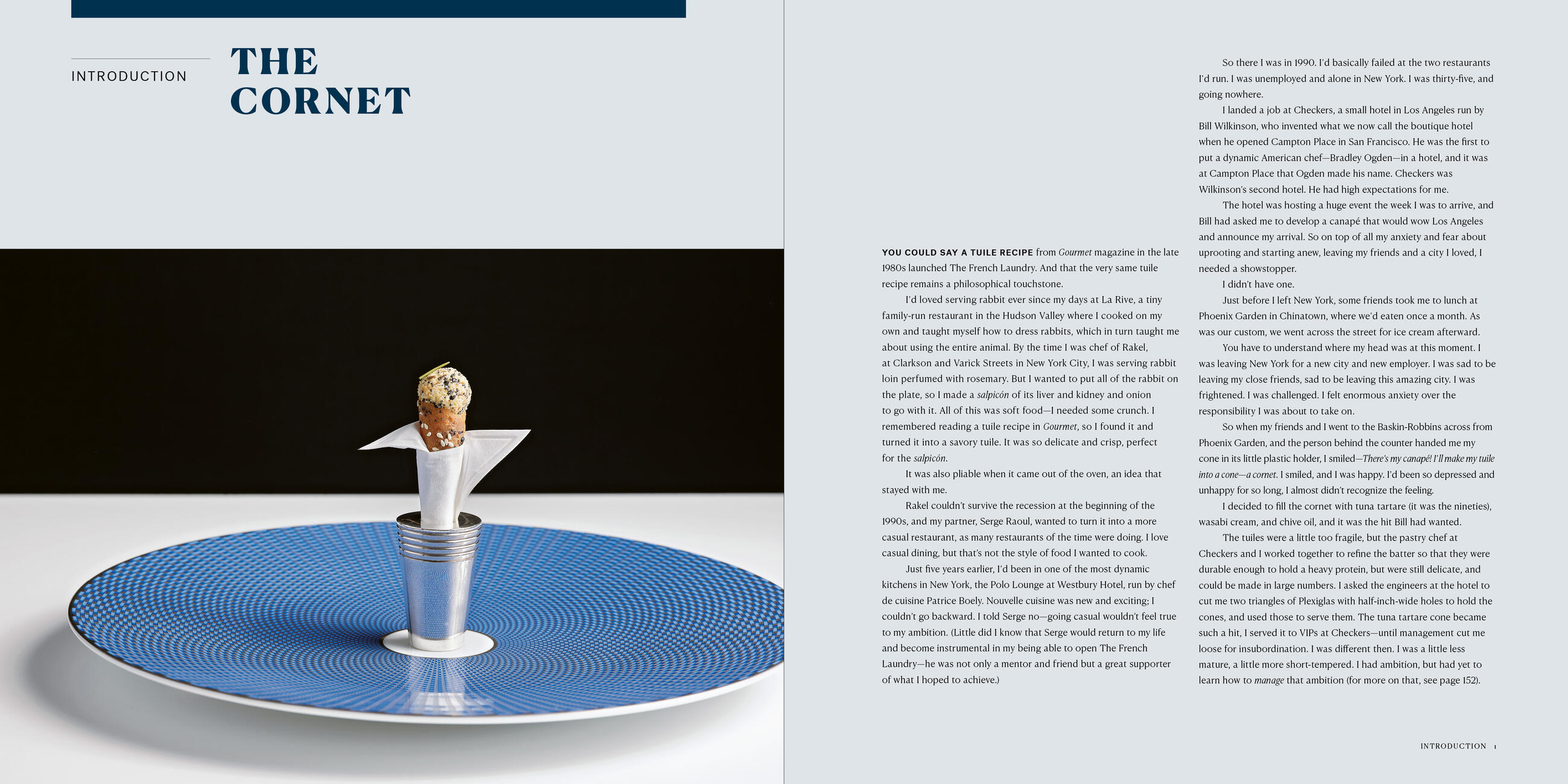

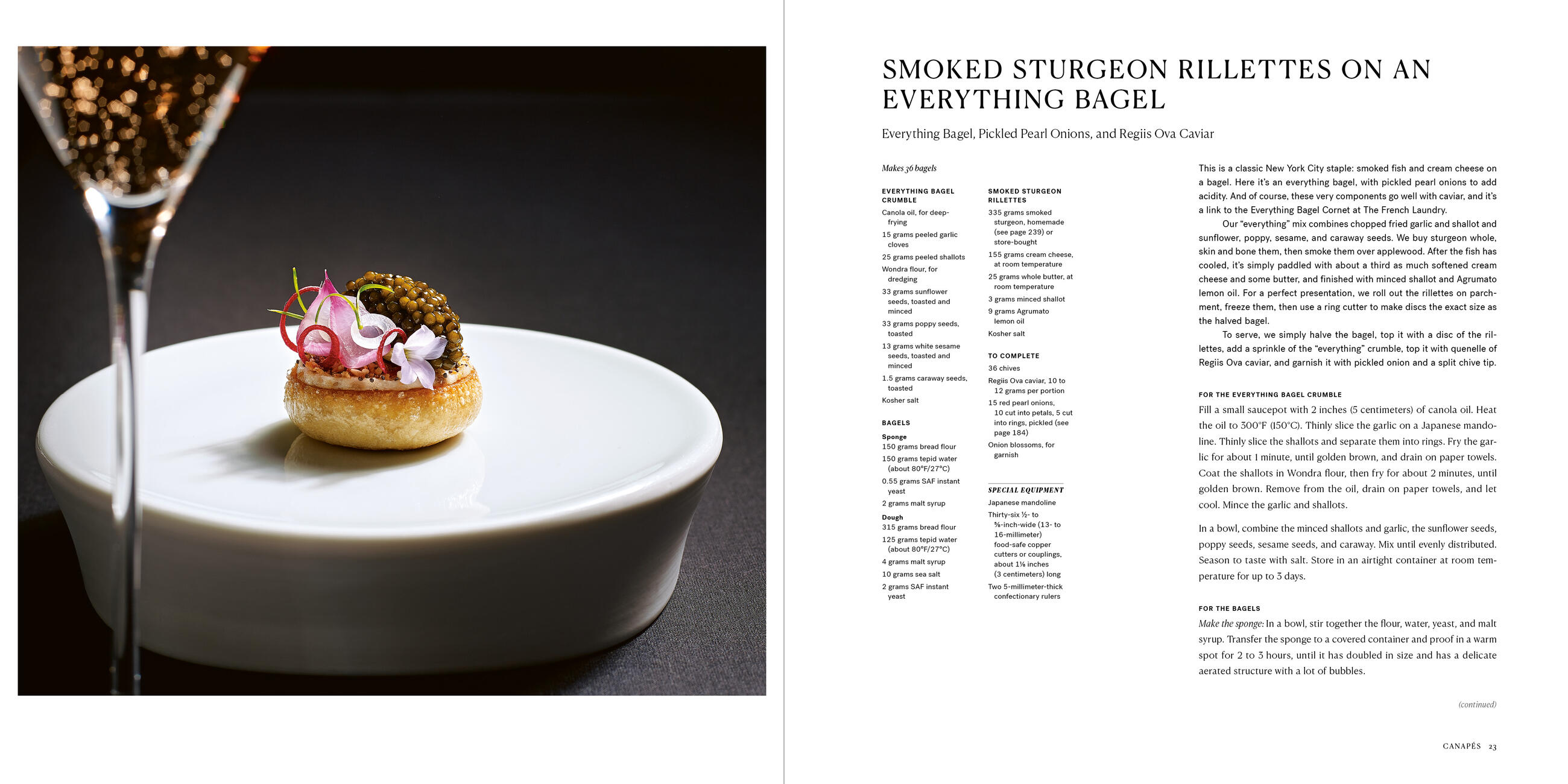

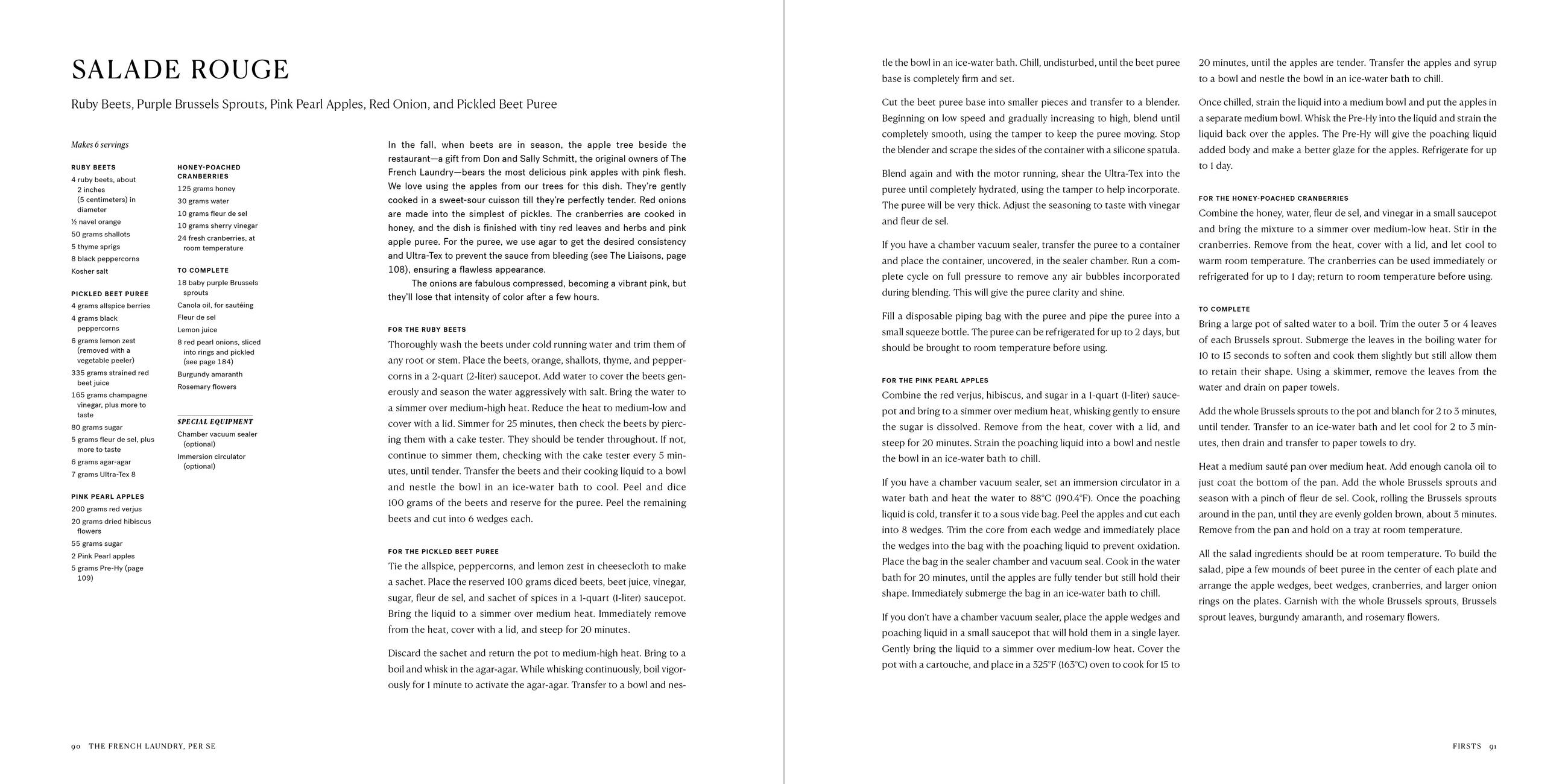

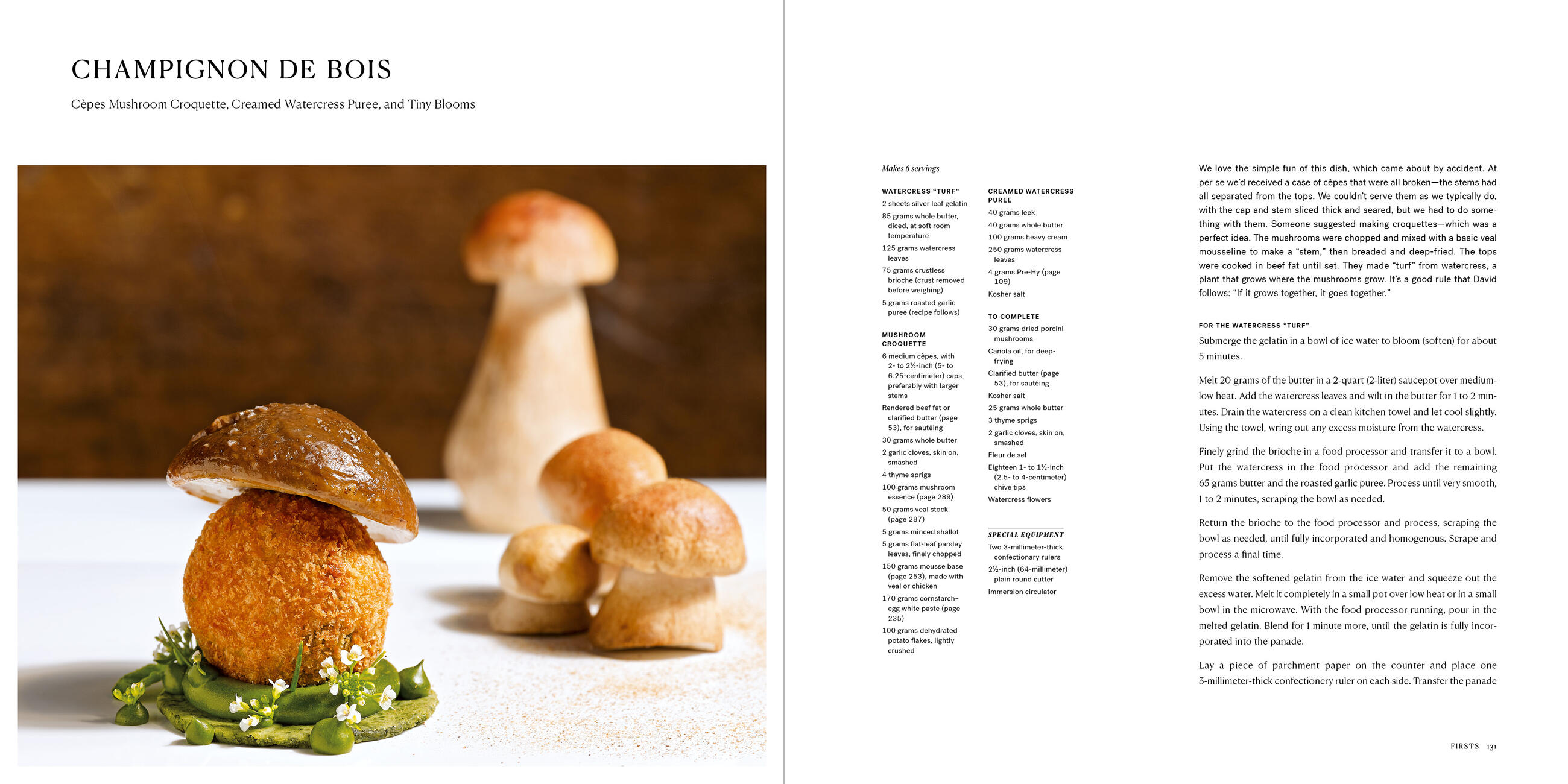

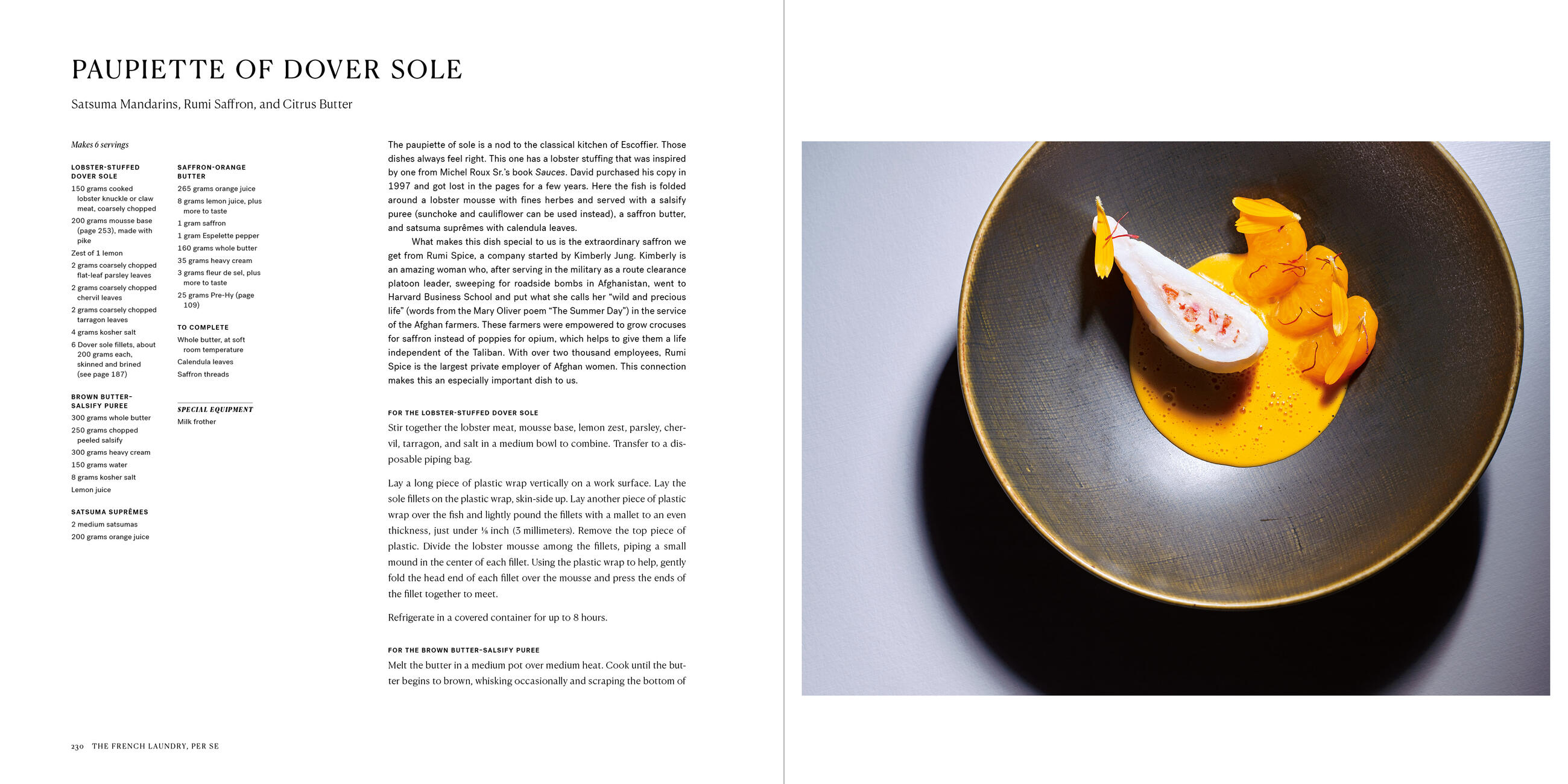

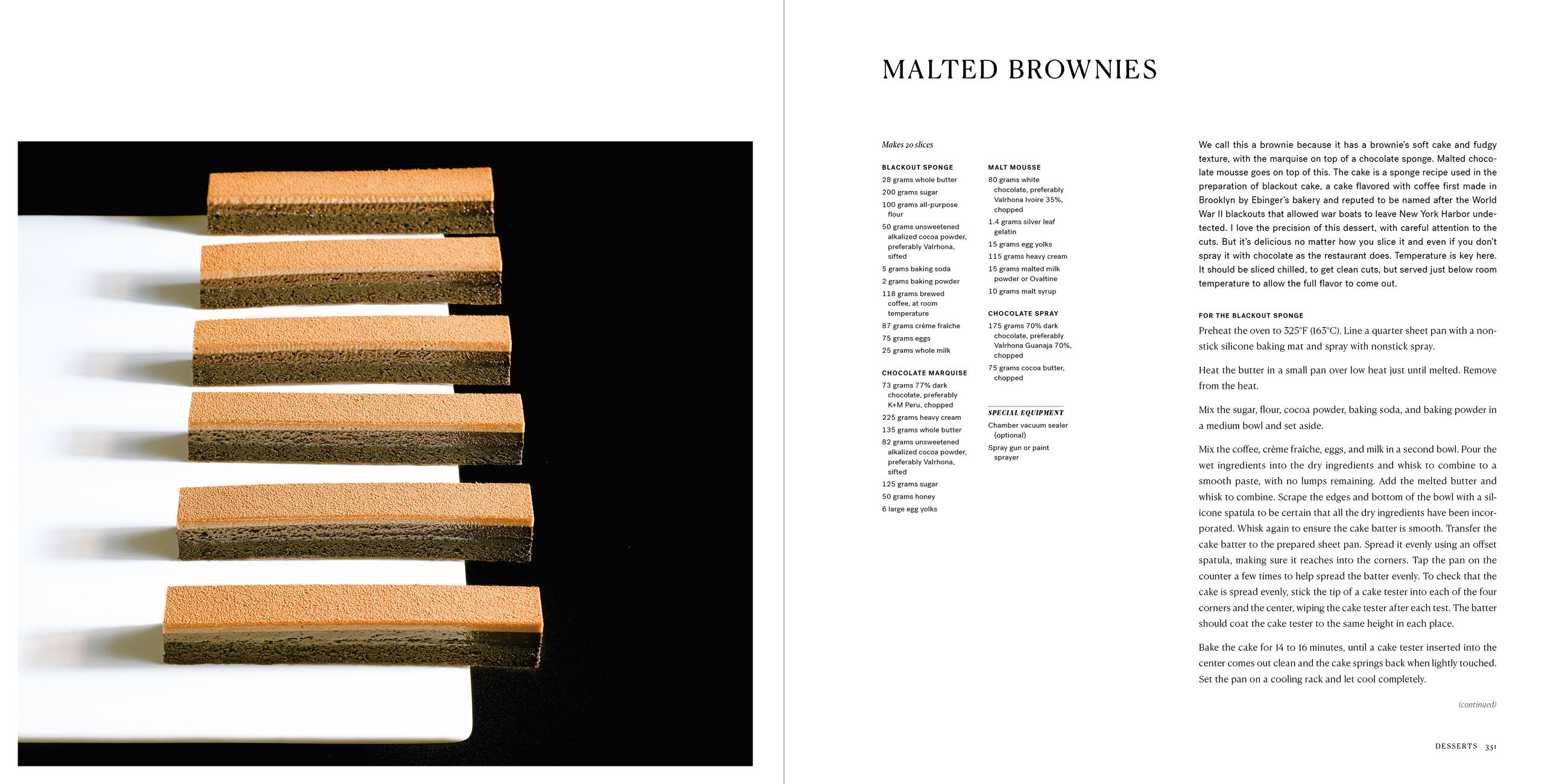

Bound by a common philosophy, linked by live video, staffed by a cadre of inventive and skilled chefs, the kitchens of Thomas Keller’s celebrated restaurants—The French Laundry in Yountville, California, and per se, in New York City—are in a relationship unique in the world of fine dining. Ideas bounce back and forth in a dance of creativity, knowledge, innovation, and excellence. It’s a relationship that’s the very embodiment of collaboration, and of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts. And all of it is captured in The French Laundry, Per Se, with meticulously detailed recipes for 70 beloved dishes, including Smoked Sturgeon Rillettes on an Everything Bagel, “The Whole Bird,” Tomato Consommé, Celery Root Pastrami, Steak and Potatoes, Peaches ’n’ Cream.

Just reading these recipes is a master class in the state of the art of cooking today. We learn to use a dehydrator to intensify the flavor and texture of fruits and vegetables. To make the crunchiest coating with a cornstarch–egg white paste and potato flakes. To limit waste in the kitchen by fermenting vegetable trimmings for sauces with an unexpected depth of flavor. And that essential Keller trait, to take a classic and reinvent it: like the French onion soup, with a mushroom essence stock and garnish of braised beef cheeks and Comté mousse, or a classic crème brûlée reimagined as a rich, creamy ice cream with a crispy sugar tuile to mimic the caramelized coating.

Throughout, there are 40 recipes for the basics to elevate our home cooking. Some are old standbys, like the best versions of beurre manié and béchamel, others more unusual, including a ramen broth (aka the Super Stock) and a Blue-Ribbon Pickle.

And with its notes on technique, stories about farmers and purveyors, and revelatory essays from Thomas Keller—“The Lessons of a Dishwasher,” “Inspiration Versus Influence,” “Patience and Persistence”—The French Laundry, Per Se will change how young chefs, determined home cooks, and dedicated food lovers understand and approach their cooking.

Series:

-

“Recipes, beautiful photographs, and lessons learned from [Keller’s] decades of cooking.”Napa Valley Register

—NPR

“Inspirational and elaborate. . . . Every elegant page projects Keller’s high standard of ‘perfect culinary execution’. . . . This superb work is as much philosophical treatise as gorgeous cookbook.”

I>Publishers Weekly, STARRED REVIEW

“The French Laundry, Per Se vividly depicts the synergy between these celebrated kitchens through a series of iconic recipes, personal essays, gorgeous photography, stories about suppliers, and tips on fine cooking techniques. . . . Revelations include [Keller’s] approach to sourcing superior ingredients, encouraging young talent, and what it takes to cook and lead a business at the highest level. With nearly 400 pages, The French Laundry, Per Se is a fascinating and eloquent exploration of one of the most significant restaurant relationships in modern times.

I>Departures

“Culinary demigod Thomas Keller’s [new] cookbook . . . is a compendium of signature recipes from his two 3-Michelin star restaurants, an intimate look at how they operate in parallel, as well as a masterclass in fine dining kitchen fundamentals.”

I>Sunset

“If you’re looking to level up your home cooking, consider Thomas Keller’s new cookbook a masterclass.”

I>WWD

“Keller poured his lifetime of knowledge from The French Laundry and Per Se into this cookbook that includes meticulously detailed recipes for seventy beloved dishes ranging from Smoked Sturgeon Rillettes on an Everything Bagel and Celery Root Pastrami to Steak and Potatoes and Peaches ‘n’ Cream. There are also a number of recipes for elevated basics like bechamel and ramen broth, along with notes on technique, stories about farmers and purveyors, and revelatory essays from the man himself. This is the foodie book of 2020.”

I>Cool Material

“To peruse The French Laundry, Per Se, it is to fall into a foodie wonderland created by a culinary imagination without borders, at least in terms of the fanciful, the elusive, the startling, the amusing, and the doubtlessly delicious. In this world, even the familiar is something different. . . . It’s a book to inspire dreams, like the 2020 version of the old Sears Roebuck ‘Dreambook,’ a catalog for foodies as well as young chefs.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use