By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

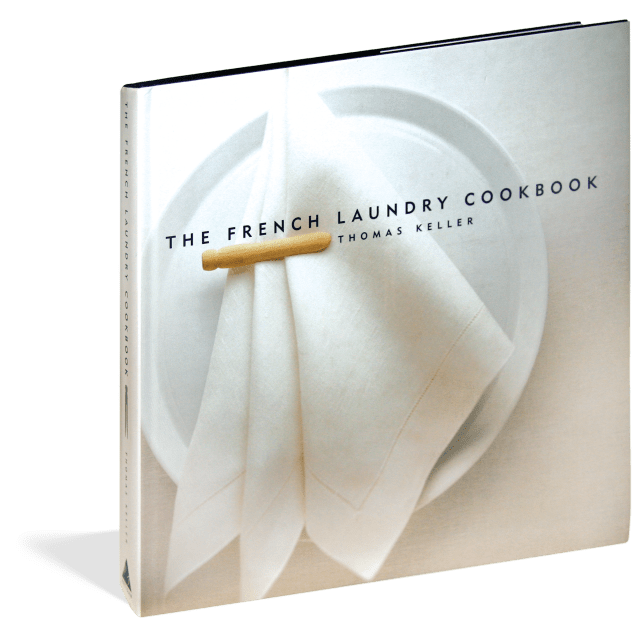

The French Laundry Cookbook

Contributors

Contributions by Susie Heller

Photographs by Deborah Jones

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 1, 1999

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Artisan

- ISBN-13

- 9781579651268

Price

$60.00Price

$75.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $60.00 $75.00 CAD

- ebook $43.99 $56.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 1, 1999. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

IACP Award Winner * Named one of “The 25 Most Influential Cookbooks From the Last 100 Years” by T: The New York Times Style Magazine

2024 marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of The French Laundry Cookbook, and the thirtieth anniversary of the acclaimed French Laundry restaurant in the Napa Valley—“the most exciting place to eat in the United States” (The New York Times). The most transformative cookbook of the century celebrates this milestone by showcasing the genius of chef/proprietor Thomas Keller himself. Keller is a wizard, a purist, a man obsessed with getting it right. And this, his first cookbook, is every bit as satisfying as a French Laundry meal itself: a series of small, impeccable, highly refined, intensely focused courses.

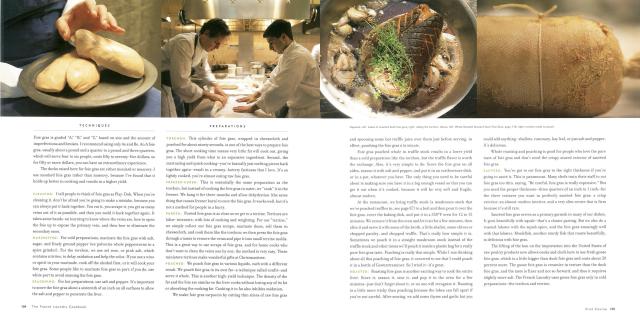

Most dazzling is how simple Keller’s methods are: squeegeeing the moisture from the skin on fish so it sautées beautifully; poaching eggs in a deep pot of water for perfect shape; the initial steeping in the shell that makes cooking raw lobster out of the shell a cinch; using vinegar as a flavor enhancer; the repeated washing of bones for stock for the cleanest, clearest tastes.

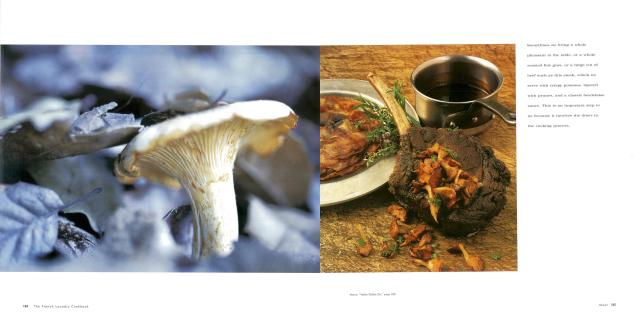

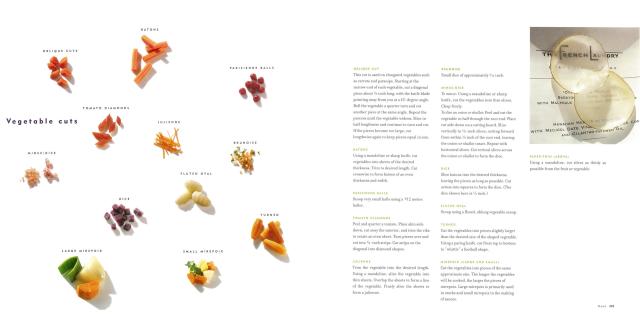

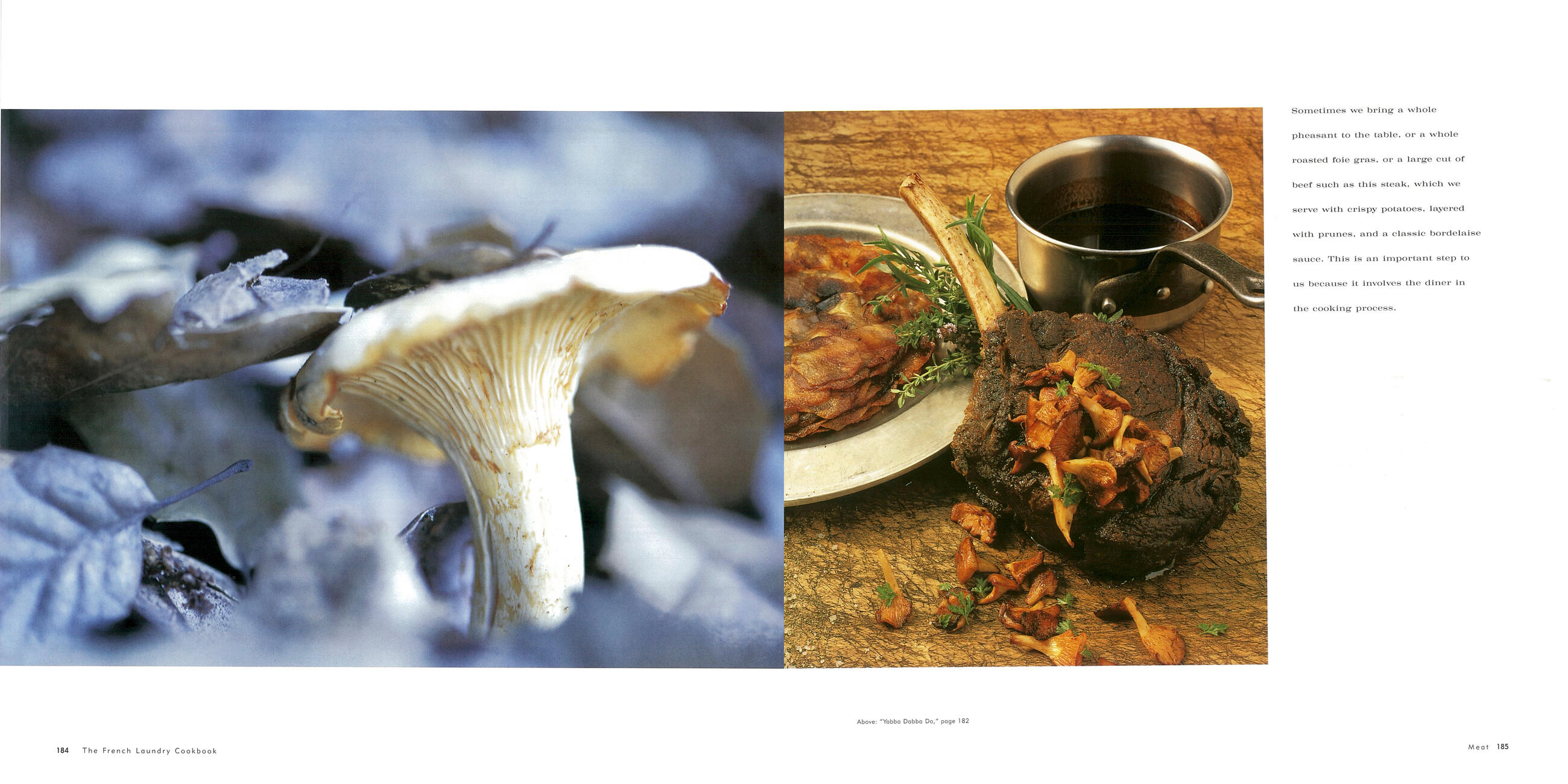

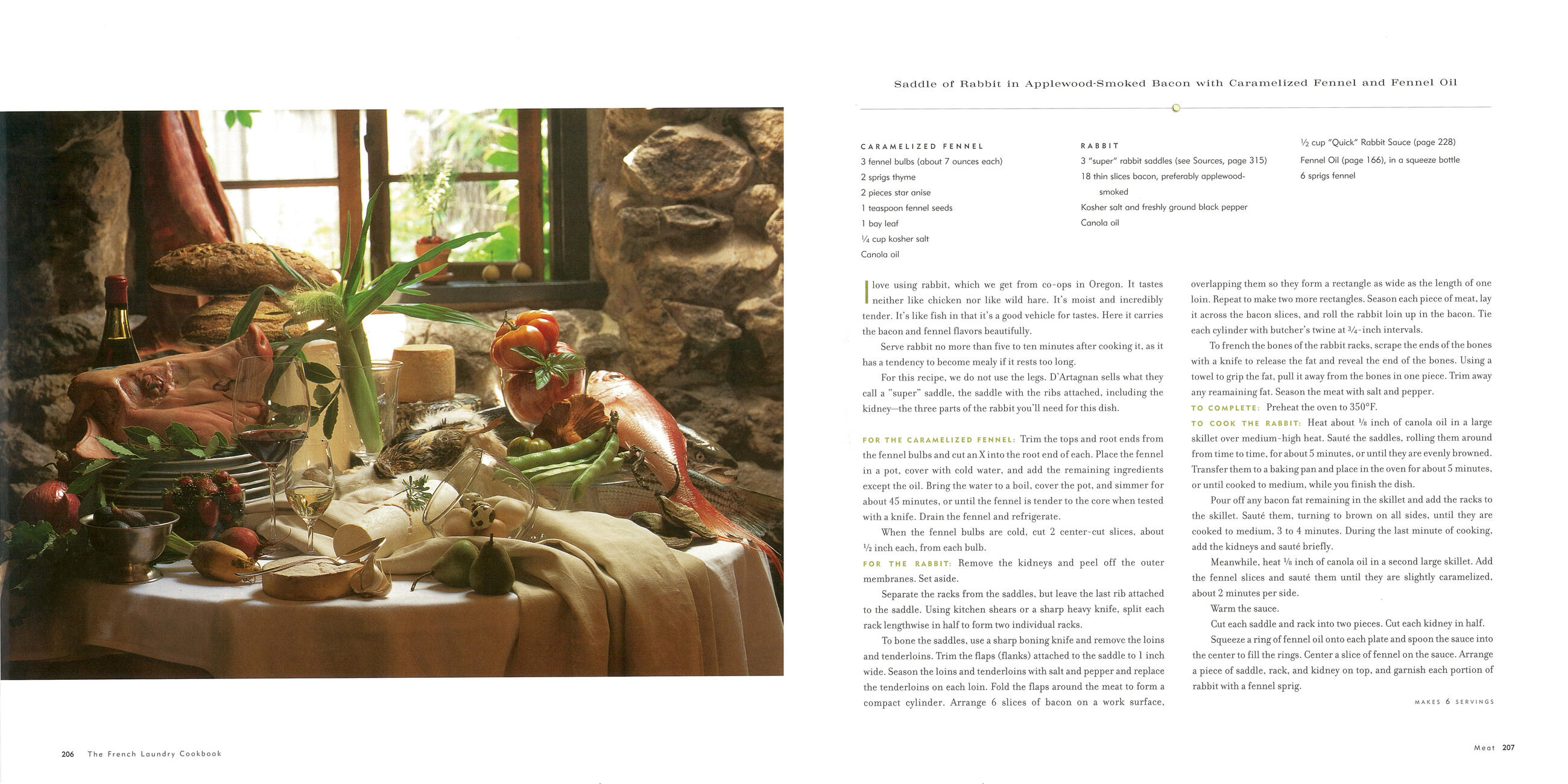

From innovative soup techniques, to the proper way to cook green vegetables, to secrets of great fish cookery, to the creation of breathtaking desserts; from beurre monté to foie gras au torchon, to a wild and thoroughly unexpected take on coffee and doughnuts, The French Laundry Cookbook captures, through recipes, essays, profiles, and extraordinary photography, one of America’s great restaurants, its great chef, and the food that makes both unique.

One hundred and fifty superlative recipes are exact recipes from the French Laundry kitchen—no shortcuts have been taken, no critical steps ignored, all have been thoroughly tested in home kitchens. If you can’t get to the French Laundry, you can now re-create at home the very experience Wine Spectator described as “as close to dining perfection as it gets.”

2024 marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of The French Laundry Cookbook, and the thirtieth anniversary of the acclaimed French Laundry restaurant in the Napa Valley—“the most exciting place to eat in the United States” (The New York Times). The most transformative cookbook of the century celebrates this milestone by showcasing the genius of chef/proprietor Thomas Keller himself. Keller is a wizard, a purist, a man obsessed with getting it right. And this, his first cookbook, is every bit as satisfying as a French Laundry meal itself: a series of small, impeccable, highly refined, intensely focused courses.

Most dazzling is how simple Keller’s methods are: squeegeeing the moisture from the skin on fish so it sautées beautifully; poaching eggs in a deep pot of water for perfect shape; the initial steeping in the shell that makes cooking raw lobster out of the shell a cinch; using vinegar as a flavor enhancer; the repeated washing of bones for stock for the cleanest, clearest tastes.

From innovative soup techniques, to the proper way to cook green vegetables, to secrets of great fish cookery, to the creation of breathtaking desserts; from beurre monté to foie gras au torchon, to a wild and thoroughly unexpected take on coffee and doughnuts, The French Laundry Cookbook captures, through recipes, essays, profiles, and extraordinary photography, one of America’s great restaurants, its great chef, and the food that makes both unique.

One hundred and fifty superlative recipes are exact recipes from the French Laundry kitchen—no shortcuts have been taken, no critical steps ignored, all have been thoroughly tested in home kitchens. If you can’t get to the French Laundry, you can now re-create at home the very experience Wine Spectator described as “as close to dining perfection as it gets.”

Series:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use