By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

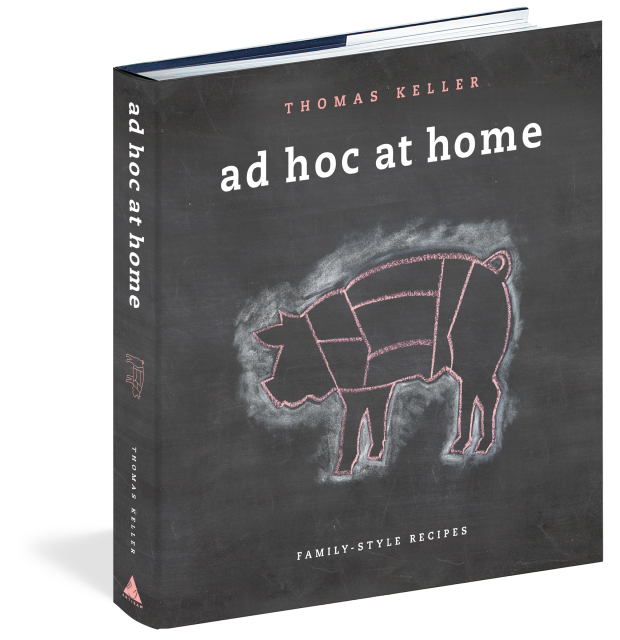

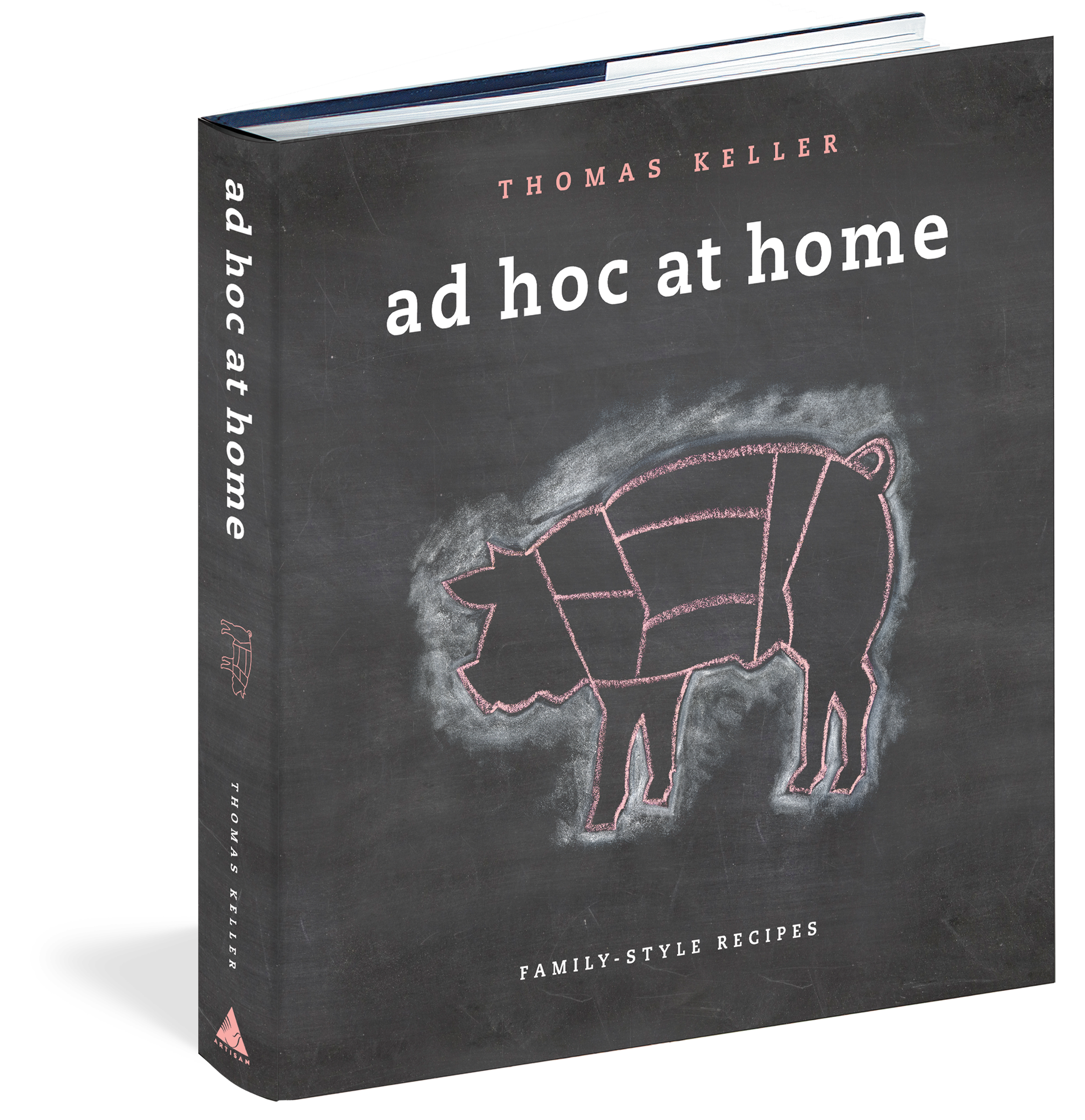

Ad Hoc at Home

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 6, 2009

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Artisan

- ISBN-13

- 9781579653774

Price

$60.00Price

$75.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $60.00 $75.00 CAD

- ebook $43.99 $56.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 6, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

New York Times bestseller

IACP and James Beard Award Winner

“Spectacular is the word for Keller’s latest . . . don’t miss it.”

—People

“A book of approachable dishes made really, really well.”

—The New York Times

Thomas Keller shares family-style recipes that you can make any or every day. In the book every home cook has been waiting for, the revered Thomas Keller turns his imagination to the American comfort foods closest to his heart—flaky biscuits, chicken pot pies, New England clam bakes, and cherry pies so delicious and redolent of childhood that they give Proust’s madeleines a run for their money. Keller, whose restaurants The French Laundry in Yountville, California, and Per Se in New York have revolutionized American haute cuisine, is equally adept at turning out simpler fare.

In Ad Hoc at Home—a cookbook inspired by the menu of his casual restaurant Ad Hoc in Yountville—he showcases more than 200 recipes for family-style meals. This is Keller at his most playful, serving up such truck-stop classics as Potato Hash with Bacon and Melted Onions and grilled-cheese sandwiches, and heartier fare including beef Stroganoff and roasted spring leg of lamb. In fun, full-color photographs, the great chef gives step-by-step lessons in kitchen basics— here is Keller teaching how to perfectly shape a basic hamburger, truss a chicken, or dress a salad. Best of all, where Keller’s previous best-selling cookbooks were for the ambitious advanced cook, Ad Hoc at Home is filled with quicker and easier recipes that will be embraced by both kitchen novices and more experienced cooks who want the ultimate recipes for American comfort-food classics.

IACP and James Beard Award Winner

“Spectacular is the word for Keller’s latest . . . don’t miss it.”

—People

“A book of approachable dishes made really, really well.”

—The New York Times

Thomas Keller shares family-style recipes that you can make any or every day. In the book every home cook has been waiting for, the revered Thomas Keller turns his imagination to the American comfort foods closest to his heart—flaky biscuits, chicken pot pies, New England clam bakes, and cherry pies so delicious and redolent of childhood that they give Proust’s madeleines a run for their money. Keller, whose restaurants The French Laundry in Yountville, California, and Per Se in New York have revolutionized American haute cuisine, is equally adept at turning out simpler fare.

In Ad Hoc at Home—a cookbook inspired by the menu of his casual restaurant Ad Hoc in Yountville—he showcases more than 200 recipes for family-style meals. This is Keller at his most playful, serving up such truck-stop classics as Potato Hash with Bacon and Melted Onions and grilled-cheese sandwiches, and heartier fare including beef Stroganoff and roasted spring leg of lamb. In fun, full-color photographs, the great chef gives step-by-step lessons in kitchen basics— here is Keller teaching how to perfectly shape a basic hamburger, truss a chicken, or dress a salad. Best of all, where Keller’s previous best-selling cookbooks were for the ambitious advanced cook, Ad Hoc at Home is filled with quicker and easier recipes that will be embraced by both kitchen novices and more experienced cooks who want the ultimate recipes for American comfort-food classics.

Series:

-

New York Times bestsellerFine Cooking

“Accessible and dazzlingly beautiful. . . . This collection is what legions of Keller fans have been waiting for, a book that allows them to replicate the merest glimmer of his culinary genius in their own homes.”

I>Publishers Weekly, starred review

“Spectacular is the word for Keller’s latest . . . don’t miss it.”

I>People

“Fun and approachable.”

I>Chicago Tribune

“A book of approachable dishes made really, really well.”

I>The New York Times

“High-class down-home cooking.”

I>New York Post

“This is real, uncomplicated home cooking. [Keller] offers everything your could want . . . and lots of bright ideas that will make you a much smarter cook.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use