Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

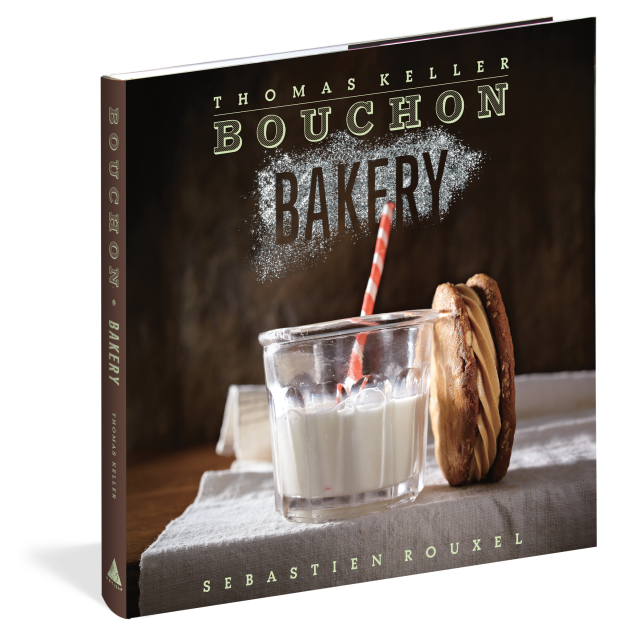

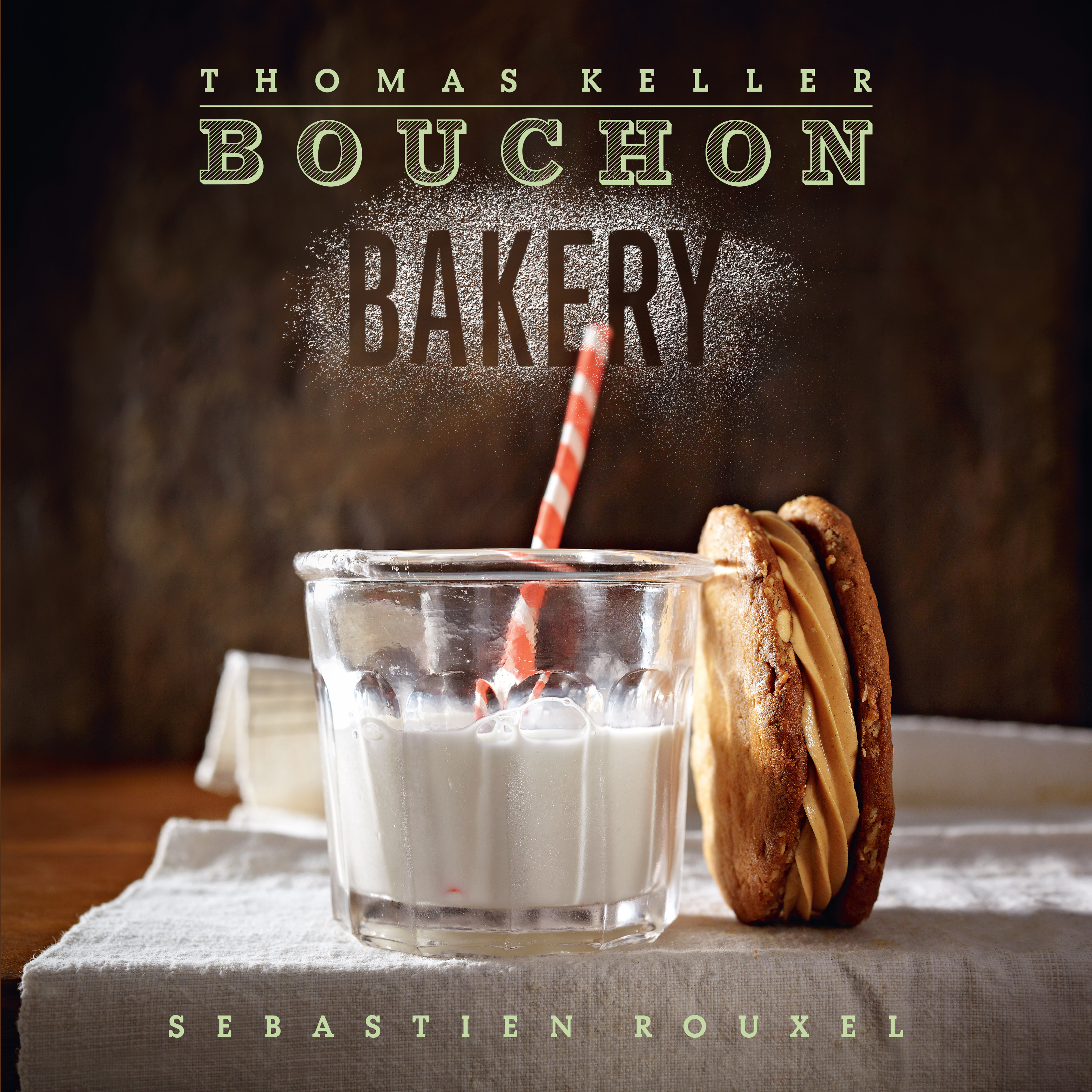

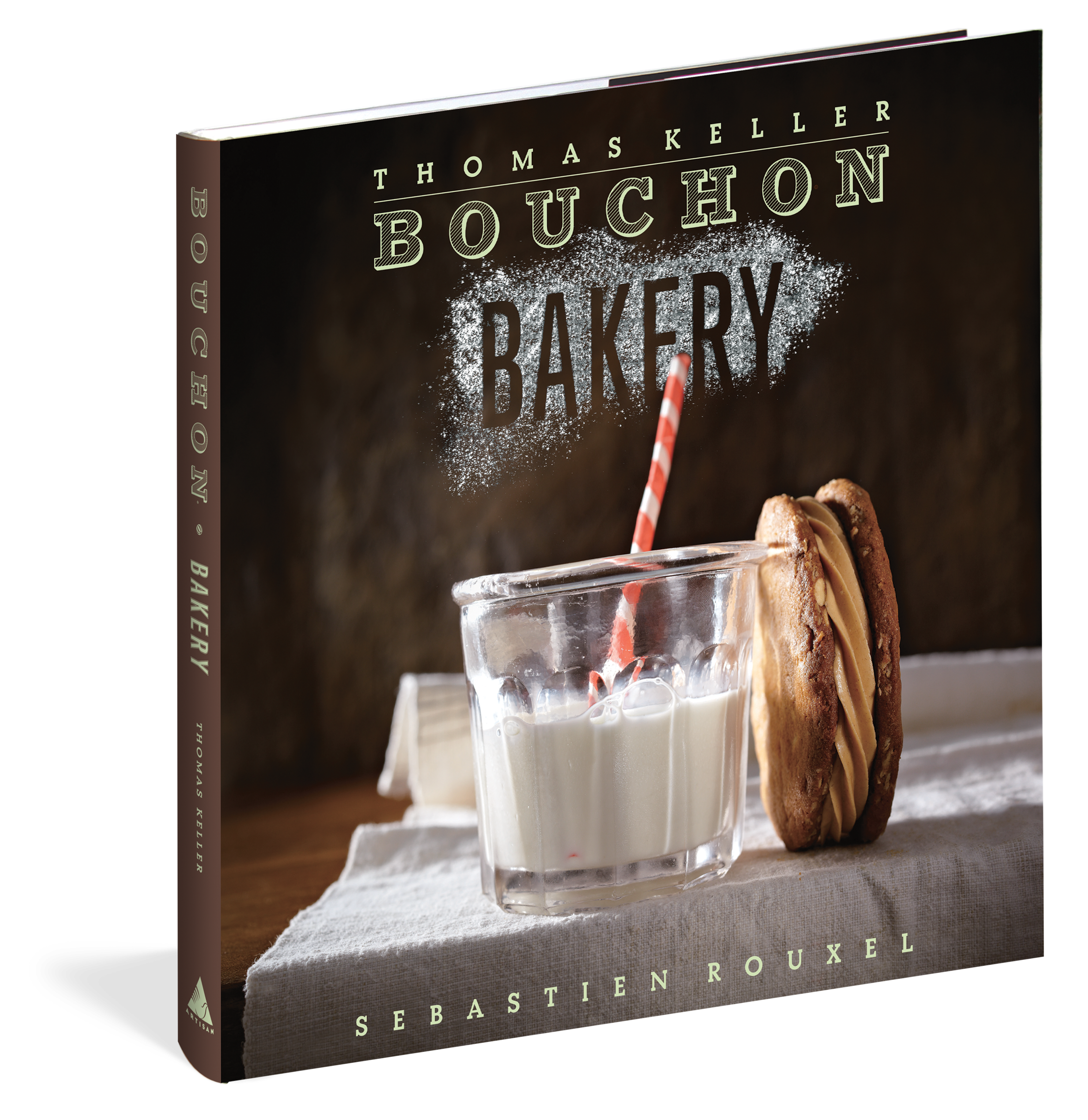

Bouchon Bakery

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 23, 2012

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Artisan

- ISBN-13

- 9781579654351

Price

$60.00Price

$75.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $60.00 $75.00 CAD

- ebook $43.99 $56.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 23, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

#1 New York Times Bestseller

Winner, IACP Cookbook Award for Food Photography & Styling (2013)

Baked goods that are marvels of ingenuity and simplicity from the famed Bouchon Bakery

The tastes of childhood have always been a touchstone for Thomas Keller, and in this dazzling amalgam of American and French baked goods, you’ll find recipes for the beloved TKOs and Oh Ohs (Keller’s takes on Oreos and Hostess’s Ho Hos) and all the French classics he fell in love with as a young chef apprenticing in Paris: the baguettes, the macarons, the mille-feuilles, the tartes aux fruits.

Co-author Sebastien Rouxel, executive pastry chef for the Thomas Keller Restaurant Group, has spent years refining techniques through trial and error, and every page offers a new lesson: a trick that assures uniformity, a subtlety that makes for a professional finish, a flash of brilliance that heightens flavor and enhances texture. The deft twists, perfectly written recipes, and dazzling photographs make perfection inevitable.

Series:

-

“Beautifully displayed, the clear and precise recipes are a breeze to follow. . . . A must-have for cooks who want to take baking to the next level.”Los Angeles Times “Inspired.”—Country Living “A beautiful monster of a baking book.”—Philadelphia City Paper “For pure food porn, Bouchon Bakery is the sweet choice. . . . Fun reading.”—Providence Journal “Stunning. . . . Surprisingly approachable.”—LA Weekly “A master’s class in baking, preserved between covers.”—Buffalo News “Simple and stunning.”—Milwaukee Journal Sentinel “The ultimate baking book.”—Charleston Post and Courier “Cookbooks don’t come bigger or more beautiful than this.”—Philadelphia Inquirer “Anyone who has had a life-altering baguette at one of Keller’s restaurants will be delighted to know that recipes for his incomparable breads, brioche, cakes, tarts, muffins, and cookies are all in this flour-dusted, sugar-rolled must-have of a cookbook.”—Houston Chronicle

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“The book tells readers exactly what they’ll need to succeed. . . . As impressive as it is exacting, this gorgeous book is a master class in professional pastry. Highly recommended.”

—Library Journal (starred review)

“Groundbreaking. . . . Both the recipes and tips make cooking at the most sophisticated level approachable for the home cook.”

—Food Wine

“Bouchon Bakery, oversize and sumptuous, brings heavyweight credentials to the genius category. . . . Those who were daunted by The French Laundry Cookbook can easily tackle homey sweets like pecan sandies or chocolate cherry scones.”

—New York Times Book Review

“With a quirky modern design and sweetly personal anecdotes, Keller’s newest tome demystifies the confections, breads, and other treats from his renowned bakeries. For everyone who’s dreamed of making desserts that look like they came out of a pastry kitchen, Keller’s guidance is icing on the cake.”

I>Bon Appétit

“The knockout new pastry testament. . . . Every strain of dough is rolled out in clear, meticulous Kellerian detail.”

—Wall Street Journal

“Abundant photos demystify even seemingly dauntless tasks.”

—Better Homes Gardens

“When Marie Antoinette said, ‘Let them eat cake,’ she couldn’t have dreamed of pastries as tasty as the ones in Thomas Keller’s kitchen.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“[Bouchon Bakery] manages to be at the same time rigorous and friendly. . . . You’ll find detailed recipes and step-by-step photographs explaining all of the basic techniques. . . . workable and even pleasurable, even for the most recalcitrant baker.”

-

“With a quirky modern design and sweetly personal anecdotes, Keller’s newest tome demystifies the confections, breads, and other treats from his renowned bakeries. For everyone who’s dreamed of making desserts that look like they came out of a pastry kitchen, Keller’s guidance is icing on the cake.” I>Bon AppetitEater

-

“Behold the big shiny restaurant cookbook of 2012 . . . . Bouchon Bakery promises to charming in the same way Ad Hoc at Home was.” —EaterFood & Wine

-

“Groundbreaking. . . . Both the recipes and tips make cooking at the most sophisticated level approachable for the home cook.” —Food WinePublishers Weekly

-

“Beautifully displayed, the clear and precise recipes are a breeze to follow. . . . A must-have for cooks who want to take baking to the next level.” —Publishers Weekly (starred review)Wall Street Journal

-

“The knockout new pastry testament . . . . Every strain of dough is rolled out in clear, meticulous Kellerian detail.” —Wall Street JournalEntertainment Weekly

-

“When Marie Antoinette said, ‘Let them eat cake,’ she couldn’t have dreamed of pastries as tasty as the ones in Thomas Keller’s kitchen.”—Entertainment WeeklyLibrary Journal

-

“As impressive as it is exacting, this gorgeous book is a master class in professional pastry. Highly recommended." —Library Journal (starred review)LA Weekly

-

“Stunning. . . . Surprisingly approachable.” I>LA WeeklyLouisville Courier Journal

-

“This book instilled me with enough confidence to actually achieve picture-worthy results. . . . Oh, and please resist cutting out the pictures and eating them. Fun and informative for the beginner, and full of helpful techniques for the old hand.” —Louisville Courier JournalBuffalo News

-

“A master’s class in baking, preserved between covers.” I>Buffalo NewsBooklist

-

“The glossy, big format lends itself well to foodies of all types who will relish the many pages of resourceful information and reliable recipes. . . . Readers really won’t need to venture beyond these pages for much else.” —Booklist