Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

Winning Your Audience

Deliver a Message with the Confidence of a President

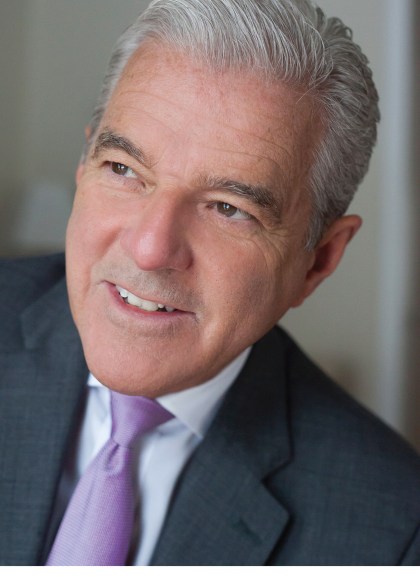

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 7, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

President Ronald Reagan taught James Rosebush to be an impactful speaker. Now he’s going to teach you.

Public speaking isn’t easy. Just ask anyone who’s ever blown a sales pitch, failed a class, or fumbled their way through a presentation because they froze up or couldn’t find the right words. No wonder more than 75 percent of people in the United States suffer from Glossophobia, the fear of speaking in front of crowds.

Luckily, public speaking isn’t some innate ability. It’s a skill. And given the right amount of time, energy, and perseverance, anyone can learn how it’s done.

In Winning Your Audience, James Rosebush draws on several decades of experience working with presidents, politicians, and business leaders to write his own manual for delivering a message with confidence. He looks back on the lessons he learned travelling the world with President Ronald Reagan, whom he served under for five years in the White House, and lays out the keys to “the Reagan speech template”: Question, Inform, Inspire, Ask.

Rosebush also studies some of the great political orators of our time. Vital lessons from the likes of Winston Churchill, Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, and President Donald Trump are distilled down to a few simple rules.

Among them are:

· Be authentic

· Know yourself

· Practice and rehearse…and then do it again

· Don’t care what your mother thinks of you

No matter what kind of speeches, toasts, or presentations you have to give, this book can help. Use it like a textbook. Write in the margins. Tear out pages. Winning Your Audience can make even the most timid speakers among us into a genuine leaders. Read it now and learn how to win your audience.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 7, 2020

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781546085966

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use