Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

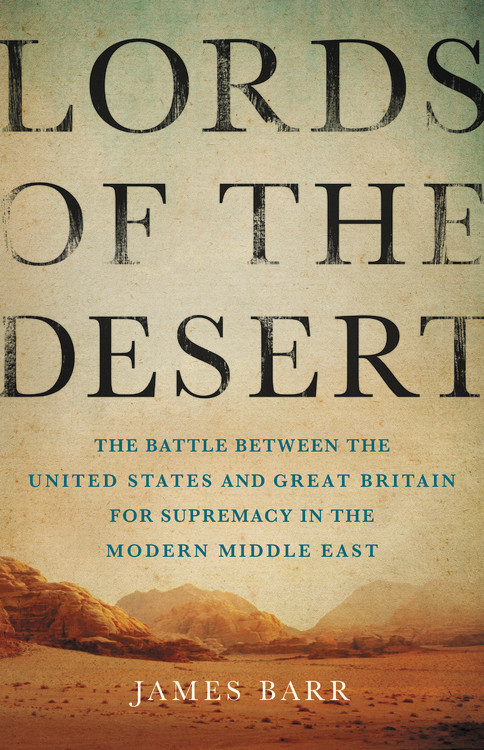

Lords of the Desert

The Battle Between the United States and Great Britain for Supremacy in the Modern Middle East

Contributors

By James Barr

Formats and Prices

Price

$35.00Price

$45.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $45.50 CAD

- ebook $22.99 $29.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 11, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

We usually assume that Arab nationalism brought about the end of the British Empire in the Middle East — that Gamal Abdel Nasser and other Arab leaders led popular uprisings against colonial rule that forced the overstretched British from the region.

In Lords of the Desert, historian James Barr draws on newly declassified archives to argue instead that the US was the driving force behind the British exit. Though the two nations were allies, they found themselves at odds over just about every question, from who owned Saudi Arabia’s oil to who should control the Suez Canal. Encouraging and exploiting widespread opposition to the British, the US intrigued its way to power — ultimately becoming as resented as the British had been. As Barr shows, it is impossible to understand the region today without first grappling with this little-known prehistory.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 11, 2018

- Page Count

- 464 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465050635

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use