Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

Leap

How to Thrive in a World Where Everything Can Be Copied

Contributors

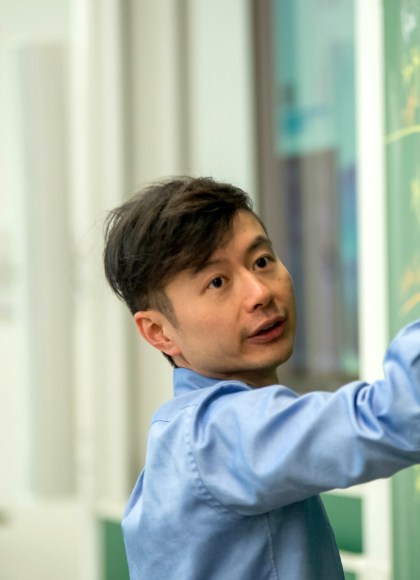

By Howard Yu

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Mass Market $9.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 12, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In a book of narrative history and practical strategy, IMD professor of management and innovation Howard Yu shows that succeeding in today’s marketplace is no longer just a matter of mastering copycat tactics, companies also need to leap across knowledge disciplines, and to reimagine how a product is made or a service is delivered. This proven tactic can protect a company from being overtaken by new (and often foreign) copycat competitors.

Using riveting case studies of successful leaps and tragic falls, Yu illustrates five principles to success that span a wide range of industries, countries, and eras. Learn about how P&G in the 19th century made the leap from handcrafted soaps and candles to mass production of its signature brand Ivory, leaped into the new fields of consumer psychology and advertising, then leaped again, at the risk of cannibalizing its core product, into synthetic detergents and won with Tide in 1946. Learn about how Novartis and other pharma pioneers stayed ahead by making leaps from chemistry to microbiology to genomics in drug discovery; and how forward-thinking companies, including China’s largest social media app — WeChat, Tokyo-based Internet service provider Recruit Holdings, and Illinois-headquartered John Deere are leaping ahead by leveraging the emergence of ubiquitous connectivity, the inexorable rise of intelligent machines, and the rising importance of managerial creativity.

Outlasting competition is difficult; doing so over decades or a century is nearly impossible — unless one leaps. Ultimately, Leap is a manifesto for how pioneering companies can endure and prosper in a world of constant change and inevitable copycats.

Genre:

-

A Strategy + Business Best Business Book of 2018

A Financial Times Best Business Book of the Month

An Inc. Top 10 Best Business Book of 2018

An 800 CEO READ Business Book to Watch in June 2018

Winner of a 2019 Axiom Business Book Award in the Business Intelligence/Innovation category

-

"Yu's research exemplifies how management theory is rigorously built and improved. He carefully documents how companies in the past have spotted and seized opportunities for growth. I find the case studies compelling and the principles intriguing for all business leaders."Clayton Christensen, Kim B Clark Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School

-

"Leap shows you how to go about deliberately thinking about adapting your business, and investigates the technological forces at work. Every leader can benefit from the wisdom found in this book."Jorgen vig Knudstrop, executive chairman, LEGO Brand Group

-

"Howard Yu argues that, even in a future age of machine intelligence, the human ability to innovate will be the primary factor enabling companies to thrive. His advice will be invaluable to managers and CEOs worldwide."V.G. Govindarajan, Coxe Distinguished Professor of Management, Tuck School of Business, Dartmouth University, and author of the New York Times bestseller Reverse Innovation

-

"At a time when big business is challenged by start-ups, when 100-year-old business models have run out of steam, and when your next competitor can come from a totally unrelated industry, Howard Yu offers important guidance on how to reinvent corporations and the need for top leaders to show compassion, pride, solidarity, and vulnerability as organizations embark on the process. The marriage of big data and humanity can fundamentally change business. I can't recommend this book highly enough."Poul Weihrauch, global president Petcare, Mars Inc.

-

"As technology's tectonic shifts reshape how companies win, Howard Yu shows the criticality of good management today. In Leap, he's written a valuable guide to help managers prepare their companies for long and successful lives."Keith Ferrazzi, chairman, Ferrazzi Greenlight and author of New York Times bestsellers Never Eat Alone and Who's Got Your Back

-

"A deeply thoughtful journey on why human curiosity and creativity matter more, not less, than ever in the new brave world of ubiquitous connectivity and smart machines. And why and how we as leaders need to learn to leap - and not just incrementally extrapolate what we already know."Jouko Karvinen, Chairman of Finnair

-

"In a world driven by global competition and constant change, businesses increasingly struggle to achieve long-term success. This book is a unique source of strategic ideas that will enable complex organizations to reinvent themselves and drive sustainable growth."Urs Rohner, Chairman, Credit Suisse Group

-

"A truly remarkable book that addresses the fundamental challenge facing managers who seek to sustain growth. Powerful case examples illustrate important concepts drawn from science and sociology as well as business."Joseph L. Bower, Donald Kirk David Professor, emeritus, Harvard Business School

- On Sale

- Jun 12, 2018

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610398800

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use