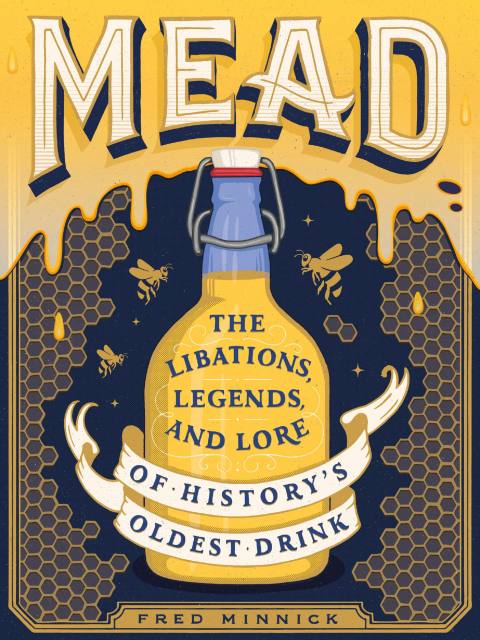

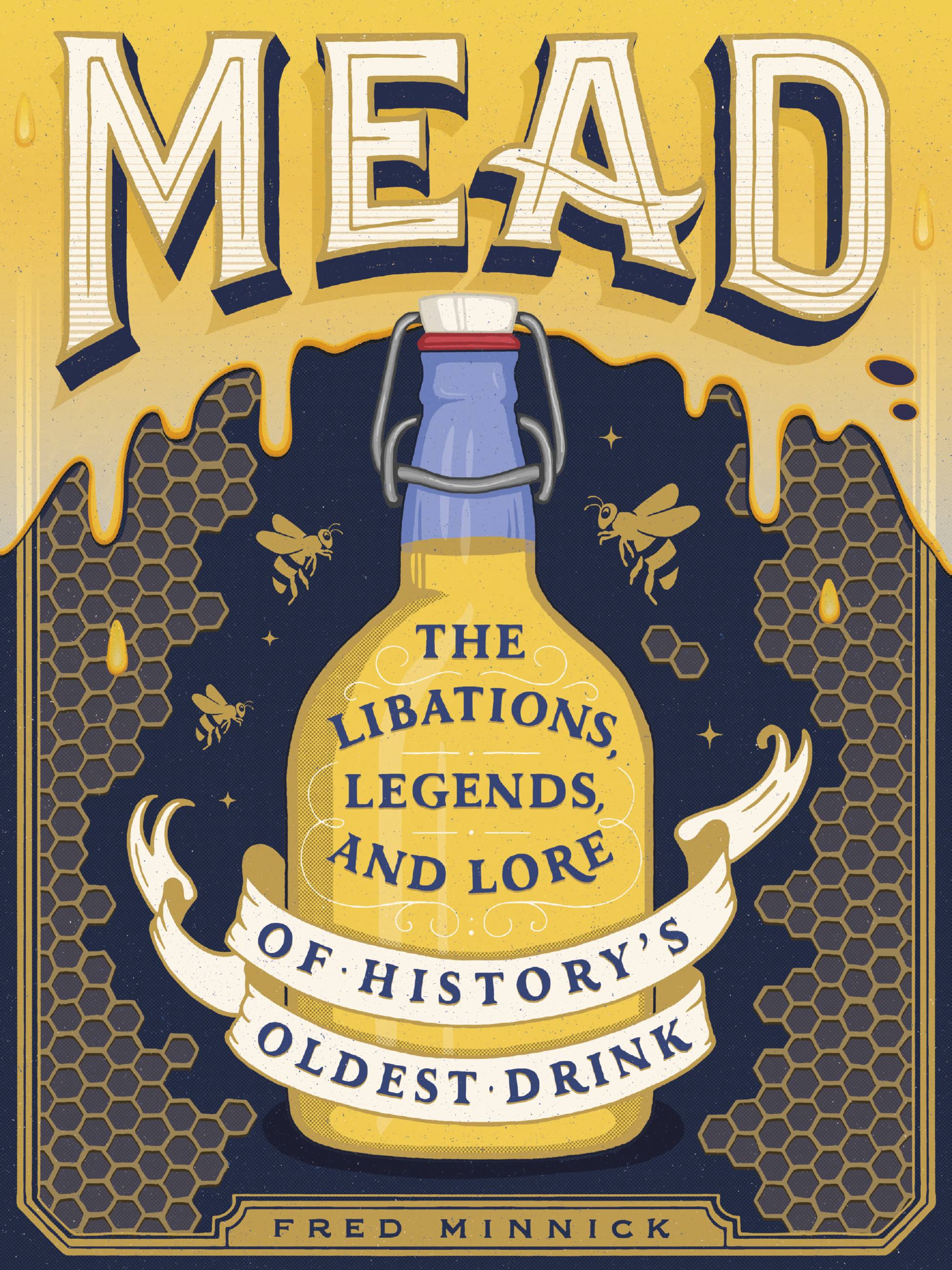

Mead

The Libations, Legends, and Lore of History's Oldest Drink

Contributors

By Fred Minnick

Illustrated by Tobias Saul

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 12, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Beloved by figures as diverse as Queen Elizabeth and Thor, the Vikings and the Greek gods, mead is one of history’s most storied beverages. But this mixture of fermented honey isn’t just a relic of bygone eras — it’s experiencing a cultural renaissance, taking pride of place in trendy cocktail bars and craft breweries across the country. Equal parts quirky historical narrative, DIY manual, and cocktail guide, Mead is a spirited look at the drink that’s been with us even longer than wine.

Mead gives readers a fascinating introduction to the rich story of this beloved beverage — from its humble beginnings to its newfound popularity, along with its vital importance in seven historic kingdoms: Greece, Rome, the Vikings, Poland, Ethiopia, England, and Russia. Pairing a quirky, historical narrative with real practical advice, beverage expert Fred Minnick guides readers through making 25 different types of mead, as well as more than 50 cocktails, with recipes from some of the country’s most sought-after mixologists.

- On Sale

- Jun 12, 2018

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762463596

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use