By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

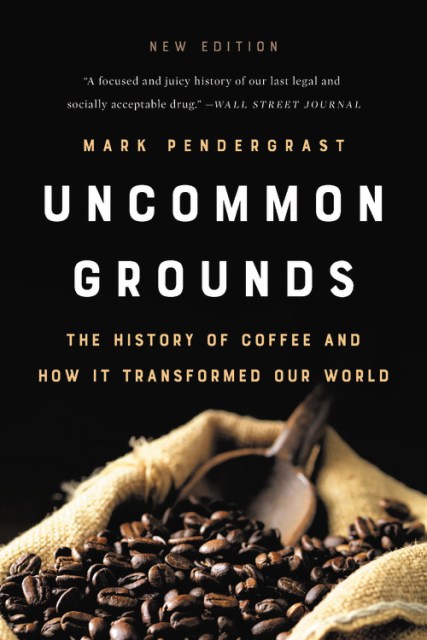

Uncommon Grounds

The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$24.99Price

$31.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback (New edition) $24.99 $31.99 CAD

- ebook (New edition) $16.99 $20.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 9, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The definitive history of the world’s most popular drug

Uncommon Grounds tells the story of coffee from its discovery on a hill in ancient Abyssinia to the advent of Starbucks. Mark Pendergrast reviews the dramatic changes in coffee culture over the past decade, from the disastrous “Coffee Crisis” that caused global prices to plummet to the rise of the Fair Trade movement and the “third-wave” of quality-obsessed coffee connoisseurs. As the scope of coffee culture continues to expand, Uncommon Grounds remains more than ever a brilliantly entertaining guide to the currents of one of the world’s favorite beverages.

Uncommon Grounds tells the story of coffee from its discovery on a hill in ancient Abyssinia to the advent of Starbucks. Mark Pendergrast reviews the dramatic changes in coffee culture over the past decade, from the disastrous “Coffee Crisis” that caused global prices to plummet to the rise of the Fair Trade movement and the “third-wave” of quality-obsessed coffee connoisseurs. As the scope of coffee culture continues to expand, Uncommon Grounds remains more than ever a brilliantly entertaining guide to the currents of one of the world’s favorite beverages.

-

"With wit and humor, Pendergrast has served up a rich blend of anecdote, character study, market analysis, and social history....Everything you ought to know about coffee is here, even how to make it."New York Times

-

"A focused and juicy history of our last legal and socially acceptable drug."Wall Street Journal

-

"Pendergrast's account satisfies because of its thoroughness....Pendergrast unearths coffee-based trade wars, health reports, and café cultures, bringing to light amusing treasures along the way."Mother Jones

-

"Ask anyone in the coffee world and they will cite this book as a favorite...[I]t gives a comprehensive understanding to the history and complexities of your favorite drink."The Kitchn

-

"Pendergrast...has produced a splendid tale, setting out all one could hope to know about coffee."Scientific American

-

"Pendergrast's broad vision, meticulous research, and colloquial delivery combine aromatically."Publishers Weekly

-

"Uncommon Grounds is not only a good read but a vital one."Washington Monthly

-

"An exhaustive, admirably ambitious examination of coffee's global impact, from its roots in 15th-century Ethiopia to its critical role in shaping the nations of Central and Latin America....Should be read by anyone curious about what goes into their daily cup of Java"Kirkus

-

"Pendergrast's sprightly, yet thoroughly scholarly, history of America's favorite hot beverage packs the pleasurable punch of a double espresso."Booklist

- On Sale

- Jul 9, 2019

- Page Count

- 480 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541699380

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use