Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

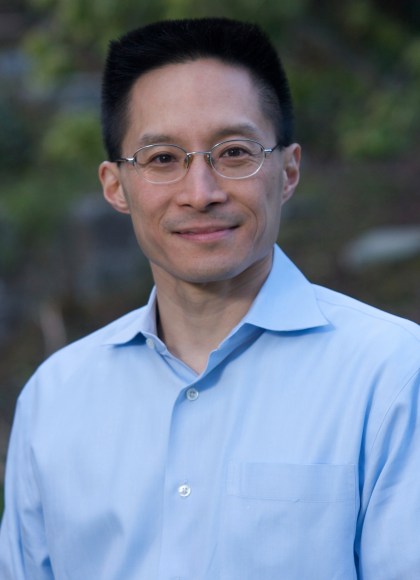

You're More Powerful than You Think

A Citizen's Guide to Making Change Happen

Contributors

By Eric Liu

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 13, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

We are in an age of epic political turbulence in America. Old hierarchies and institutions are collapsing. From the election of Donald Trump to the upending of the major political parties to the spread of grassroots movements like Black Lives Matter and $15 Now, people across the country and across the political spectrum are reclaiming power.

Are you ready for this age of bottom-up citizen power? Do you understand what power truly is, how it flows, who has it, and how you can claim and exercise it?

Eric Liu, who has spent a career practicing and teaching civic power, lays out the answers in this incisive, inspiring, and provocative book. Using examples from the left and the right, past and present, he reveals the core laws of power. He shows that all of us can generate power-and then, step by step, he shows us how. The strategies of reform and revolution he lays out will help every reader make sense of our world today. If you want to be more than a spectator in this new era, you need to read this book.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 13, 2018

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541773660

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use