Promotion

Sign up for our newsletters to receive 20% off! Shop now. Exclusions apply.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

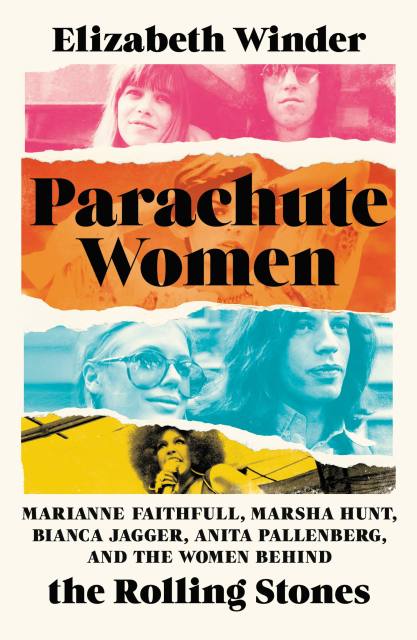

Parachute Women

Marianne Faithfull, Marsha Hunt, Bianca Jagger, Anita Pallenberg, and the Women Behind the Rolling Stones

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 11, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Discover the true story of the four women who worked tirelessly behind the scenes to help shape and curate the image of The Rolling Stones—perfect for fans of Girls Like Us.

The Rolling Stones have long been considered one of the greatest rock-and-roll bands of all time. At the forefront of the British Invasion and heading up the counterculture movement of the 1960s, the Stones' innovative music and iconic performances defined a generation, and fifty years later, they're still performing to sold-out stadiums around the globe. Yet, as the saying goes, behind every great man is a greater woman, and behind these larger-than-life rockstars were four incredible women whose stories have yet to be fully unpacked . . . until now.In Parachute Women, Elizabeth Winder introduces us to the four women who inspired, styled, wrote for, remixed, and ultimately helped create the legend of the Rolling Stones. Marianne Faithfull, Marsha Hunt, Bianca Jagger, and Anita Pallenberg put the glimmer in the Glimmer Twins and taught a group of straight-laced boys to be bad. They opened the doors to subterranean art and alternative lifestyles, turned them on to Russian literature, occult practices, and LSD. They connected them to cutting edge directors and writers, won them roles in art house films that renewed their appeal. They often acted as unpaid stylists, providing provocative looks from their personal wardrobes. They remixed tracks for chart-topping albums, and sometimes even wrote the actual songs. More hip to the times than the rockers themselves, they consciously (and unconsciously) kept the band current—and confident—with that mythic lasting power they still have today.

Lush in detail and insight, and long overdue, Parachute Women is a group portrait of the four audacious women who transformed the Stones into international stars, but who were themselves marginalized by the male-dominated rock world of the late '60s and early '70s. Written in the tradition of Sheila Weller's Girls Like Us, it's a story of lust and rivalries, friendships and betrayals, hope and degradation, and the birth of rock and roll.

-

Apple, "Must Listen" (July 2023)

Town & Country, "Best Books to Read This Summer" (July 2023) -

"Winder spotlights how the vast influence of these women on the Stones has largely been hidden in the shadow of the band’s monolithic mythos... Parachute Women is a step toward according these women their rightful place in music culture..."Washington Post

-

“Perhaps more fascinating than the Stones themselves are the women who helped create them… Pack this in your beach bag and you're nearly guaranteed—sorry!—satisfaction.”Town & Country

-

"...[D]elicious, gossipy, glamorous, but also [an] emotional and thoughtful read...AirMail

-

"Pacily written, Parachute Women is a gripping, thought-provoking read with a surprisingly broad appeal. Even the Stones-averse will find a lot to love here."Classic Rock

-

"Winder expertly weaves the stories of these four women who floated in and out of the Stones’ orbit, and often simultaneously or overlapping. Far more than just 'rock chicks,' they helped mold the men and their music—even if it came at their own expense."Houston Press

-

“Delicious… as a reader you're swayed between boggling at the outlaw glamour and eye-rolling at the drama and double standards. The women certainly emerge as more original and dynamic personalities than Mick'n'Keef."Spectator (UK)

-

“A fascinating portrait …. backed up by keenly described historical background and an expert understanding of 1960s and ’70s rock culture. The result is a wild ride worthy of rock’s heyday.”Publishers Weekly

-

"A vivid portrait of the women behind 'the world’s first rock stars'... Gossipy, entertaining, and quite right in insisting on the central role of women in making an iconic band iconic."Kirkus

-

"This feminist look at the history of the women of the Rolling Stones would make an excellent addition to collections looking to round out its offerings on rock and women’s history."Library Journal

-

“A multi-faceted … refreshing portrait of four women who dared to be themselves in the hypermasculine world of rock.”Booklist

-

“I've been waiting for someone to write this book since I read Marianne Faithfull's memoir on a cross-country flight thirty years ago. The story of how women dismissed as consorts, groupies, and open secrets created the aesthetic that brought the Rolling Stones to glory—and significantly contributed to their music, too—has been buried too long. Winder embraces its dishiness while going deeper, showing how these brilliant, strong women shaped cultural history even as the men around them tried to contain and even destroy them.”Ann Powers, author of Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black and White, Body and Soul in American Music

- On Sale

- Jul 11, 2023

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781580059596

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use