Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

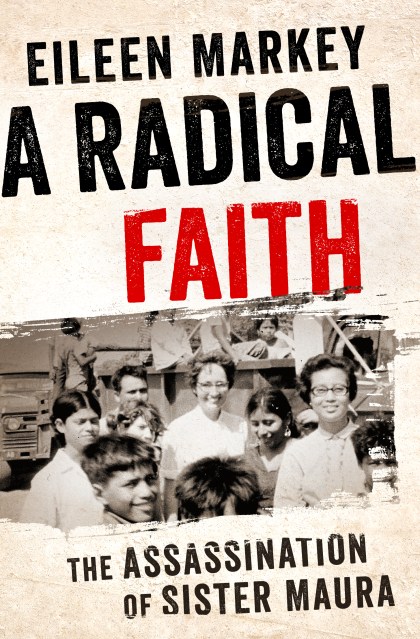

A Radical Faith

The Assassination of Sister Maura

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $26.99 $34.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 8, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In A Radical Faith, journalist Eileen Markey breathes life back into one of these women, Sister Maura Clarke. Who was this woman in the dirt? What led her to this vicious death so far from home? Maura was raised in a tight-knit Irish immigrant community in Queens, New York, during World War II. She became a missionary as a means to a life outside her small, orderly world and by the 1970s was organizing and marching for liberation alongside the poor of Nicaragua and El Salvador.

Maura’s story offers a window into the evolution of postwar Catholicism: from an inward-looking, protective institution in the 1950s to a community of people grappling with what it meant to live with purpose in a shockingly violent world. At its heart, A Radical Faith is an intimate portrait of one woman’s spiritual and political transformation and her courageous devotion to justice.

Genre:

-

"In death, Maryknoll Sister Maura Clarke became known as a symbol of the brutality of El Salvador's pitiless conflict in the 1980s. In this rare and beautiful book, Eileen Markey brings Maura to life. From her childhood in a tightly knit Irish Catholic neighborhood to her departure for Nicaragua in 1959 and subsequent murder in El Salvador, Maura's life became interwoven with the tumultuous history of Cold War Central America. Drawing on personal correspondence and extensive interviews, Markey skillfully evokes the transformation of the Catholic Church during those turbulent decades, crafting a searing testament to the meaning of faith amidst the hard choices imposed by desperate circumstances."Cynthia Arnson, Director, Latin American Program, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars

-

"A Radical Faith brings excitement, tension, and compassion to an overlooked story...Rich details and solid storytelling convey one nun's story of her dedication to God and her fellow humans."Kirkus Reviews

-

"I've always believed that responsibility, honesty, and faith are the three pillars of a strong character. Sister Maura Clarke, who recognized the humanity in everyone she met-from schoolchildren in the Bronx to farmers in Nicaragua-lived a life that served as a testament to that strength. Eileen Markey's beautifully told narrative reminds us of Maura's courage in the face of brutal dictators and shocking suffering. It's an important story that has been forgotten for too long, and Markey's book returns Maura to her deserved place in history."Martin Sheen

- On Sale

- Nov 8, 2016

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568585741

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use