Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

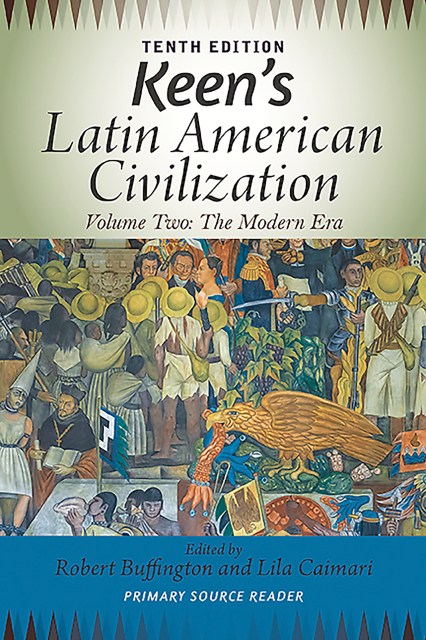

Keen's Latin American Civilization, Volume 2

A Primary Source Reader, Volume Two: The Modern Era

Contributors

By Lila Caimari

Formats and Prices

Price

$40.00Format

Format:

- Trade Paperback $40.00

- ebook $25.99

- ebook $25.99

- Trade Paperback $42.00

- Trade Paperback $75.00

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 28, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The tenth edition of Keen's Latin American Civilization inaugurates a new era in the history of this classic anthology by dividing it into two volumes. This second volume retains most of the modern period sources from the ninth edition but with some significant additions including a new set of images and a wide range of new sources that reflect the latest events and trends in contemporary Latin America. The 75 excerpts in volume two provide foundational and often riveting first-hand accounts of life in modern Latin America. Concise introductions for chapters and excerpts provide essential context for understanding the primary sources.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jul 28, 2015

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Avalon Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780813348919

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use