Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

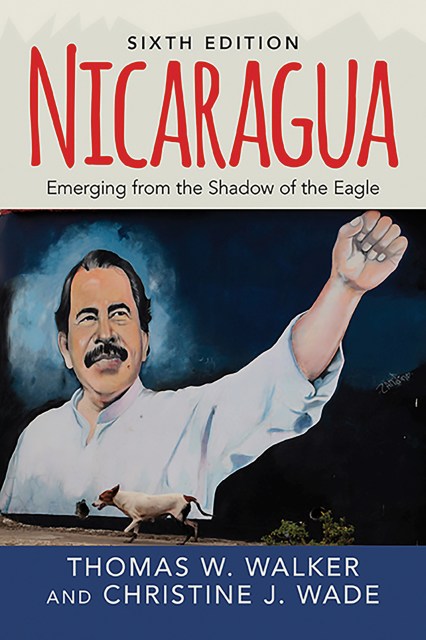

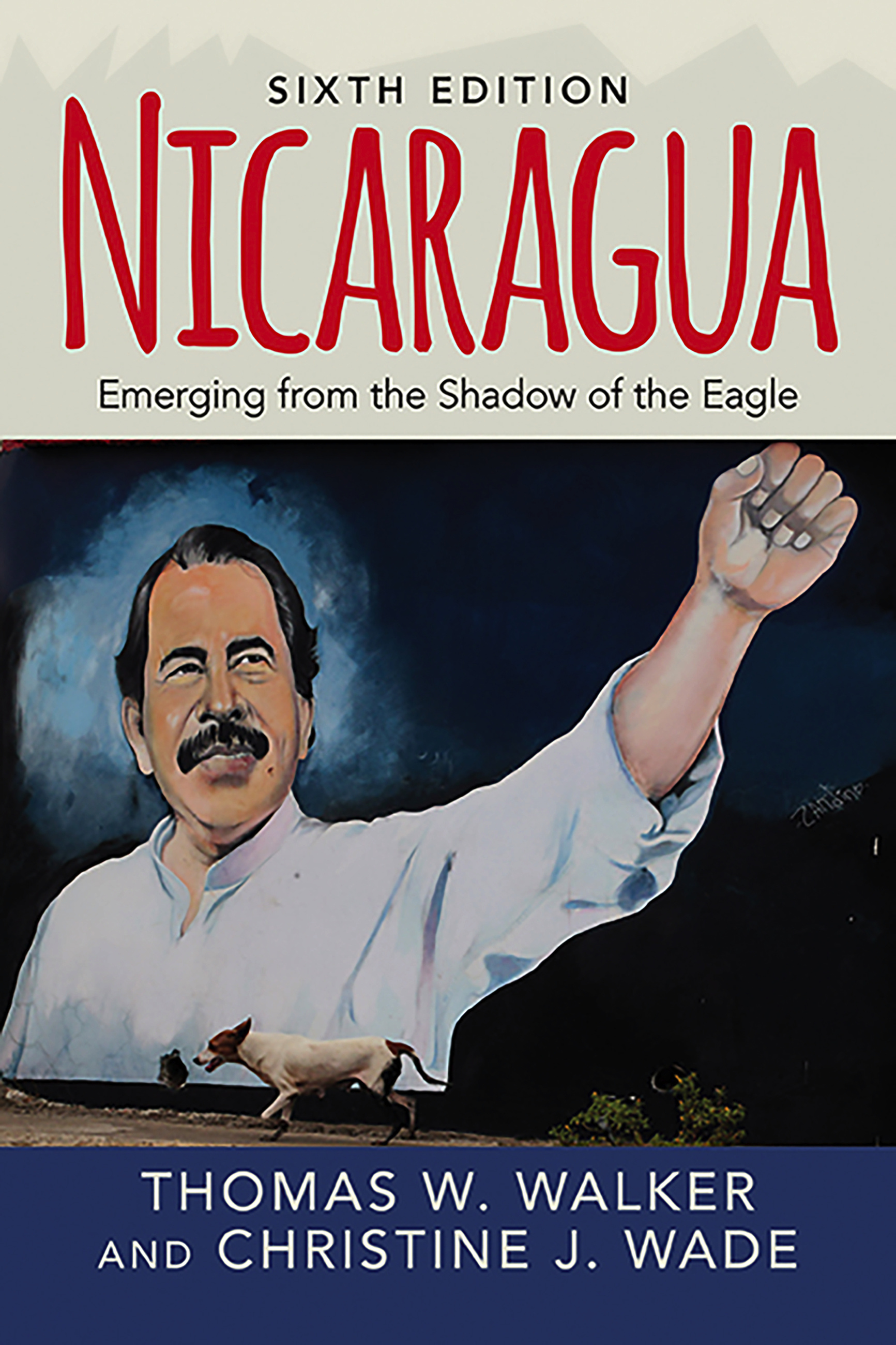

Nicaragua

Emerging From the Shadow of the Eagle

Contributors

By Christine J. Wade

Formats and Prices

Price

$35.00Format

Format:

- Trade Paperback $35.00

- ebook $22.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 2, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Nicaragua: Emerging from the Shadow of the Eagle details the country's unique history, culture, economics, politics, and foreign relations. Its historical coverage considers Nicaragua from pre-Columbian and colonial times as well as during the nationalist liberal era, the U.S. Marine occupation, the Somoza dictatorship, the Sandinista revolution and government, the conservative restoration after 1990, and consolidation of the FSLN's power since the return of Daniel Ortega to the presidency in 2006.

The thoroughly revised and updated sixth edition features new material covering political, economic, and social developments since 2011. This includes expanded discussions on economic diversification, women and gender, and social programs. Students of Latin American politics and history will learn the how the interventions by the United States—the “eagle” to the north—have shaped Nicaraguan political, economic, and cultural life, but also the extent to which Nicaragua is increasingly emerging from the eagle's shadow.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 2, 2016

- Page Count

- 264 pages

- Publisher

- Avalon Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780813349862

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use